BONDS OF WOMANHOOD

Copyright 2021 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Delfino, Susanna, 1949- author.

Title: Bonds of womanhood : slavery and the decline of a Kentucky plantation / Susanna Delfino.

Description: Lexington : The University Press of Kentucky, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021049365 | ISBN 9780813154831 (hardcover ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813154886 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813154855 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Grigsby, Susan Preston Shelby, 1830-1891Ethics. | Women, WhiteKentucky19th centuryBiography. | Social changeKentucky19th century. | Women, WhiteKentuckySocial conditions19th century. | Women, WhiteKentuckyEconomic conditions19th century. | African American womenKentuckySocial conditions19th century. | SlaveryEconomic aspectsKentucky19th century. | SlaverySocial aspectsKentucky19th century. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC F445.N4 D45 2021 | DDC 976.9/03092 [B]dc23/eng/20211027

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Member of the Association of University Presses

For Catherine, Michele, Stephanie

Noi non potemo aver perfetta vita senza amici.

(We cannot have perfect life without friends.)

Dante, Convivio, IVXXV

Contents

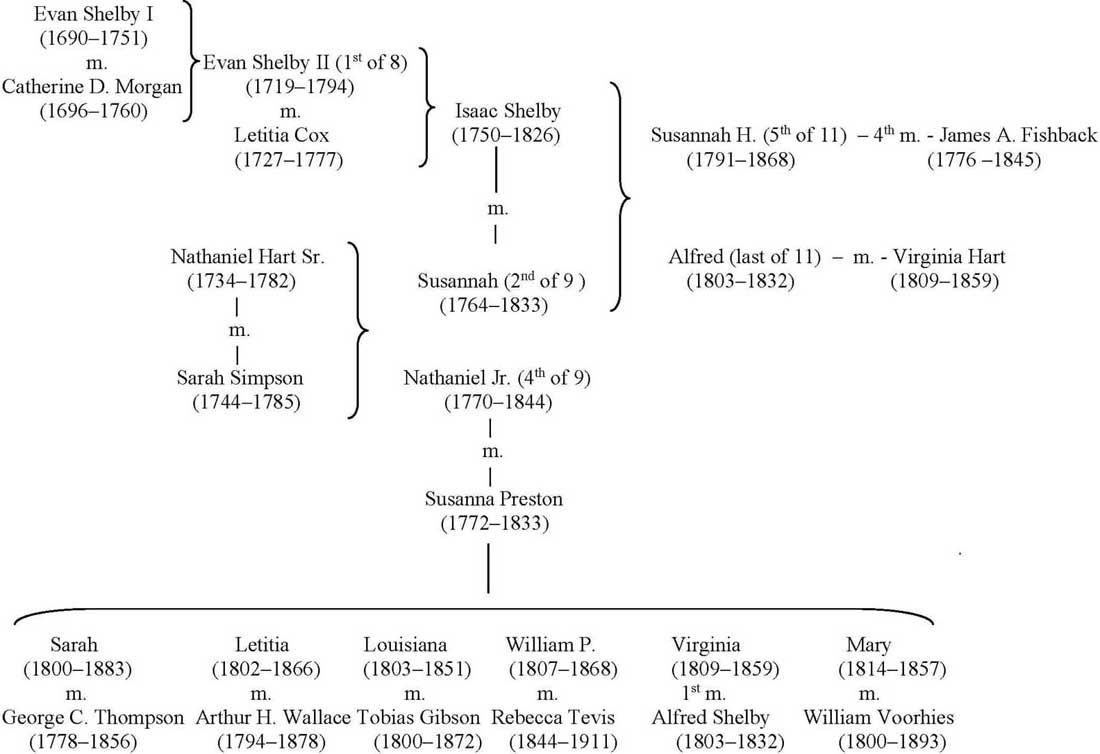

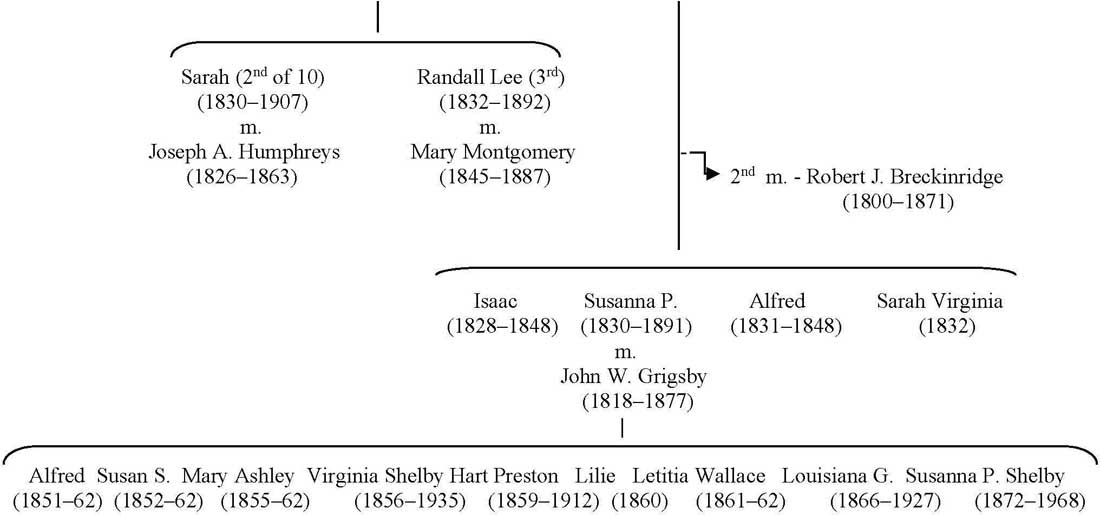

Essential Genealogy of the Shelby and Hart Families

Introduction

This book situates itself at the intersection of my long dedication to the study of antebellum southern manufacturing with a later-developed interest in womens history, and it owes its realization to the inspirations derived from a number of fortunate and interlocking circumstances.

It all began at the 1999 annual meeting of the Southern Historical Association in Fort Worth, Texas. There, at the conclusion of a brainstorming meeting among a few women scholars, Michele Gillespie and I agreed to undertake the joint editing of a collection of essays on free, ordinary womens workpaid and unpaidin the Old South. This intellectually gratifying experience set in motion a virtuous circle that, in the span of a few years, would reorient my scholarship in a markedly gendered perspective.

Not long after the publication of Neither Lady nor Slave (2002) I started thinking of a book project on the impact of economic modernization on the lives of antebellum white southern women as beneficiaries of expanded opportunities for gainful employment in an enslaving society. During my first reconnaissance, Kentucky provided a most stimulating context for my purpose, not only on account of the high rate of industrial development, low percentage of the enslaved over total population, and remarkable presence of immigrantscoming from or through the Northeastthat the state recorded in 1850. Dry statistical figures apart, upon considerations of a social and cultural nature as well, Kentucky was an ideal region for investigation. In fact, the egalitarian and antislavery attitude of its early settlers, combining over time with ever-growing influences from the Northeast via the Ohio River, gave the Bluegrass State a special character of progressivism that greatly contributed to placing it in the forefront of the antebellum Souths difficult path to modernization.

Because of the capitalistic nature of an economy based on enslaving humans, the US South was, in a sense, modern from the very beginning. Yet southern slavery differed from northern capitalism in important ways, and this difference impinged upon the scope and timing of the transformations simultaneously occurring in either section of the country during the first half of the nineteenth century. Genuine modernization involved, in fact, far more than economic diversification and industrial development. It entailed deep changes in mentality and sensibility toward labor and its relation to capital. These were at odds with human bondage.

Caught in a conflict between a vision of full-fledged modernization that necessarily implied the annihilation of slavery, and the immense wealth that property in enslaved persons embodied, Kentuckians were pulled between tradition and change. Anticipating the conclusion reached by the great economic historian Alexander Gerschenkron a century laterthat each country or region has its own way to industrializationeven the most resolute enemies of the peculiar institution ultimately seemed to subscribe to the opinion, held by most fellow white southerners in other states, that industrial development was compatible with the continuation of bonded labor. Yet they all missed the crucial point that modernization is not simply measured by industrial wealth and industrial output. The quintessential example of the battleground between aversion to slavery and economic interest, Kentucky stood therefore as a perfect test case for the viability of modernization in a slavery-based society.

Reflecting the surge in womens participation in the US labor market during the previous decade, the 1860 federal census included them for the first time in the count of the population engaged in some sort of remunerated work. The census returns did not differentiate individuals by sex, however, making it impossible to determine the precise extent of females involvement.

Scores of white women directly contributed to the rise of the industrial order either as factory operatives or as outworkers paid by the piece in connection with the same. Others simply benefited from the expansion of businesses and continued to ply traditional trades, either as self-employed workers or as dependents at some small enterprise, signally in garment-making. Regardless of the nature of their jobs, however, all lower-class white women shared the same stringent necessity that forced them to toil long hours for trifling wages.

Conversely, the many middle-class white women who, from the 1840s, increasingly engaged in income-generating occupations as directors of schools or owners of commercial undertakings like dressmaking and millinery often did so either to supplement dwindling family incomes or to seek a measure of

Member of the Association of University Presses

Member of the Association of University Presses