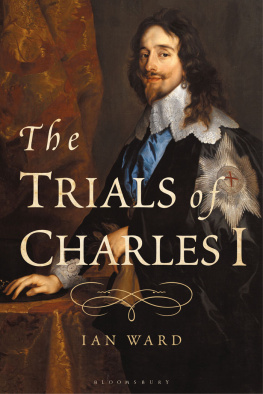

The Trials of Charles I

The Trials of Charles I

Ian Ward

BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2023

Copyright Ian Ward, 2023

Ian Ward has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

Cover image: Portrait of King Charles I of England, Scotland and Ireland (16001649),

end 1630s. Found in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst,

Copenhagen Getty Images

Cover design: Graham Robert Ward

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-3500-2497-7

PB: 978-1-3500-2514-1

ePDF: 978-1-3500-2498-4

eBook: 978-1-3500-2499-1

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

For Ross, fellow historian, with whom I enjoyed so many great conversations about the trials of Charles Stuart

Contents

We will start in the tranquil surroundings of north Hampstead. On the evening of 18 October 2012. The opening night for a new play by the celebrated British dramatist Howard Brenton. In his youth, Brenton had earned a reputation as a fiery, left-leaning, writer. Determined, in his words, to toss a petrol-bomb through the proscenium arch. A theatre-loving Leveller, we might say. In more recent years, Brenton has written a number of plays revisiting significant historical moments, and personalities. The play which was about to be premiered that evening was one of these. 55 Days was about the final eight weeks, minus a day, in the life of King Charles I. The events leading up to his trial, which commenced on 20 January 1649, and culminated in his execution ten days later.

The time frame is more closely set by the purge of Parliament, named after Colonel Thomas Pride, on 6 December 1648. On that day, Pride excluded around a 140 MPs, chiefly Presbyterian, with a scattering of Levellers, who were likely to oppose the intended trial of the king. The idea of putting the king on trial had bounced around for a while. Certainly months, in some quarters years. But Prides purge represented the first concerted move to make a reality of the idea. It also represented something else, as apparent as it was prosaic. In the end, the fate of the king, and the nation, would be decided by the sword. By the army, more closely a small group of senior officers, headed by Oliver Cromwell and his son-in-law Henry Ireton. This is not to say that they somehow caused the kings trial and execution. Questions of causation are rarely so easily resolved. But they made it happen.

Brentons play invites us to consider a series of questions regarding both the writing of history and the writing of the trial of King Charles I. The first is that history in dramatic form seems a little different. We expect to find history written in textbooks and monographs, critical essays perhaps. We also expect it to make certain claims to veracity, to how things really happened and why. We are less comfortable with the idea that the historian is free to imagine things, in order to create dramatic coherence. Which is what Brenton does. Whilst much of 55 Days is drawn from original sources, much is not. At this point we find ourselves approaching a defining distinction in historical writing. Between those who are more easily reconciled to the idea that history is an art-form, and those who prefer to think that it might be reduced to scientific principles.

This distinction finds familiar shape in the alternative arguments of Whig and revisionist historians. Put very simply the Whig historian tends to write larger histories which assume a narrative form. A species of story-telling, or so their revisionist critics suppose, which tends to rub away the contingencies. In his seminal critique, The Whig Interpretation of History , Herbert Butterfield likened it to history written by strolling minstrels, and urged historians to write the vicissitudes back in. Whether Carlyle can be properly termed an ironist is debatable. But Brenton is, writing a particular story of the trial and execution of Charles I, which is, on its terms, perfectly credible, and indeed coherent. Whilst not supposing that it is the only credible account, or indeed the most credible.

The next insight is the matter of choice. Any historian is faced with choices, most commonly of place and moment. The same choices which face the dramatist. Brenton chooses just the fifty-five days, and centres his story around the character of Charles Stuart. It is, in a sense, the obvious choice. The events of January 1649 lend themselves to dramatic presentation. We might reasonably assume that Shakespeare, had he been alive, would have written his Tragedy of King Charles around the same. There again, if discretion militated towards a history instead, he might have chosen a different moment. Or at least included a few more moments. The murder of the Duke of Buckingham perhaps in 1628. The execution of Strafford, the battle of Naseby, the Putney debates, the siege of Colchester. Various possibilities which might attract a different historian in a different moment. Various contingencies which would write a different history. We will revisit all of these, and plenty more, in our history.

Of course, the original choice was to decide to write a play about Charles Stuart at all. It might seem obvious. Few events in English history seemed more remarkable, to contemporaries at least, than the trial and execution of their king. A world turned upside down, heralding, some supposed, the Second Coming. Time contextualizes. But even so. Three and a half centuries on, it still seems a remarkable occurrence. Well worthy of a play, and some history. Of course, the broader moment has always fascinated. The great seventeenth-century time, as Carlyle and Dickens variously called it. The England of cavaliers and roundheads, roaming the country disembowelling one another. Oddly relatable. There is, as Sellars and Yeatman intimated in their wonderful pastiche, 1066 and All That , something of the wrong but wromantic, and the right but repulsive, in all of us. And within this great time, the events of January 1649 assume a pivotal place. And not just for reason of chronology. The place of the Crown in the English Constitution was never the same again.

The most extraordinary judicial body in English history, it has been suggested, of the court assembled at Westminster Hall. And the framers of the English Bill of Rights too, and the great reform acts to follow. We will revisit the glorious revolution of 1688 in due course. A history that can only be imagined, and written, in the shadow of January 1649.

Next page