Contents

Page List

John Laughland

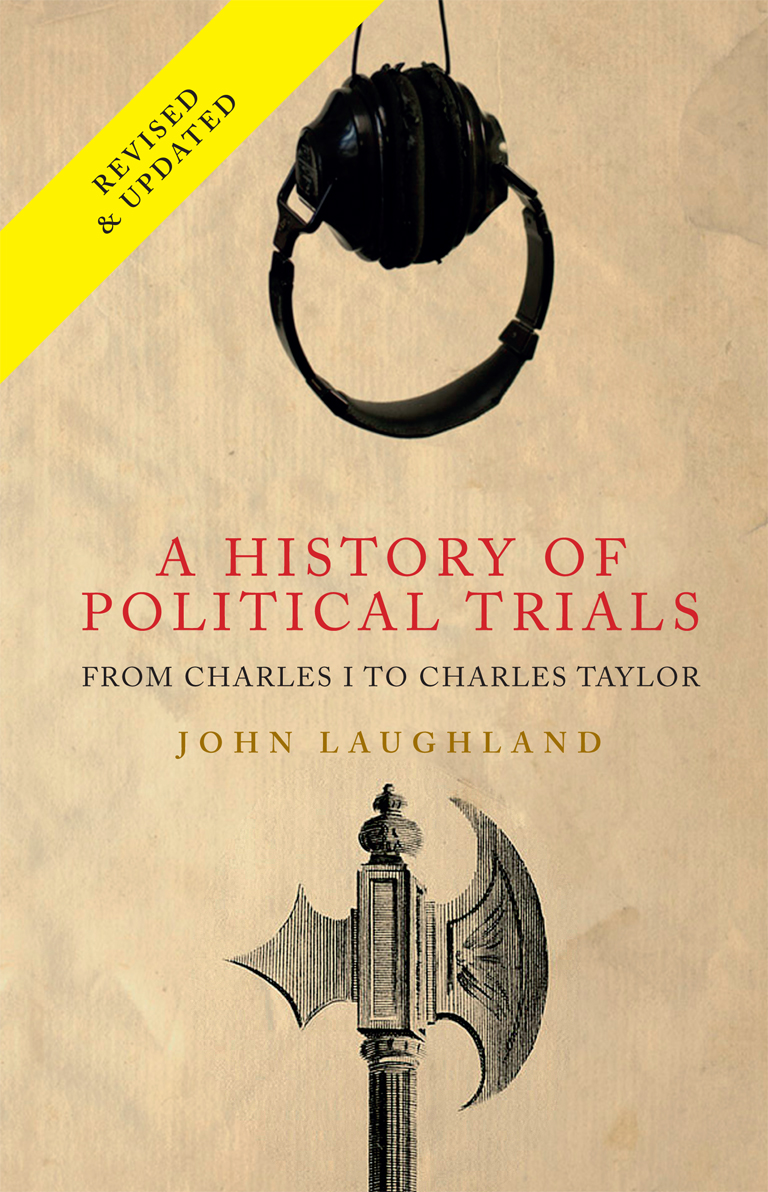

A History of Political Trials

From Charles I to Charles Taylor

Second Edition

Peter Lang Ltd

International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

www.peterlang.com

Peter Lang Ltd 2016

This is a revised edition of A History of Political Trials, 2008

ISBN 978-1-906165-00-0 (pb) and 978-1-906165-05-5 (hb)

by the same author

The right of John Laughland to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the Publishers.

British Library and Library of Congress

Cataloguing-in Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library,

UK, and the Library of Congress, USA.

ISBN 978-1-906165-52-9 (print)

ISBN 978-3-0353-0798-6 (eBook)

Cover design: Dan Mogford

About the author(s)/editor(s)

John Laughland is Director of Studies at the Institute of Democracy and Cooperation in Paris. Having studied at Oxford, where he also completed a doctorate, he has taught at universities in Paris and Rome. He has published several books including The Tainted Source: The Undemocratic Origins of the European Idea (1997), Travesty: The Trial of Slobodan Milosovic and the Corruption of International Justice (2007) and Schelling versus Hegel, from German Idealism to Christian Metaphysics (2008). He is a regular commentator on international affairs on television and in the press.

About the book

The modern use of international tribunals to try heads of state for genocide and crimes against humanity is oft en considered a positive development. Many people think that the establishment of special courts to prosecute notorious dictators represents a triumph of law over impunity. In A History of Political Trials, John Laughland takes a very diff erent and controversial view. He shows that trials of heads of state are in fact not new, and that previous trials thoughout history have themselves violated the law and due process.

It is the historical account which carries the argument. By examining trials of heads of state and government throughout history fi gures as diff erent as Charles I, Louis XVI, Erich Honecker, Saddam Hussein and Charles Taylor Laughland shows that modern trials of heads of state have ugly historical precedents. In their diff erent ways, all the trials he describes were marked by arbitrariness and injustice, and many were gross exercises in hypocrisy. Political trials, he fi nds, are only the continuation of war by other means.

With short and easy chapters, but the fruit of formidable erudition and wide reading, this book will force the general reader to re-examine prevailing opinions on this subject.

A formidable and well-documented counterblast to a developing modern orthodoxy, expressing a point of view that many readers will not even have suspected existed, let alone read.

Anthony Daniels, The Spectator

A useful and controversial contribution to the debate about victors justice, and a valuable warning that international war crimes tribunals need to operate with precision and care.

Jonathan Steele, The Guardian

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

| 5

To Emily, for Lydia, with love

| 7

Can one save a king who is on trial? He is dead as soon as he appears in front of his judges.

(Peut-on sauver un roi mis en jugement? Il est mort quand il parat devant ses juges)

Danton, remark to Thodore de Lameth, November 1792 (Thodore de Lameth, Mmoires, p. 243)

We mean [by the rule of law], in the first place, that no man is punishable or can be made to suffer in body or goods except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary courts of the land.

A. V. Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution, ch. 4

| 11

In writing this book, I have contacted many people out of the blue, asking them for help. I have been immensely touched by the generosity with which they have responded, spent time on my requests, and imparted their knowledge. I am in debt to the following for their kindness:

Chris Black, David Brewer, Richard Crampton, Istvn Dek, Vesselin Dimitrov, Penelope Evans, James Felak, Aaron Fichtelberg, Ivaylo Gatev, Milan Grba, David Jacobs, Lszl Karsai, Lasse Lehtinen, Radomr Mal, Takis Nitis, Hannu Rautkallio, Filip Reyntjens, Urmi Shah, Phil Taylor, Kjetil Tronvoll, Ilya Vlassov, James Ward.

| 13

Whenever heads of state go on trial these days and the phenomenon is becoming increasingly common you can usually rely on someone to say that the event is unprecedented. In October 2007 a leading human rights organization said that the extradition of the former Peruvian president, Alberto Fujimori, to his native country from Chile was the first time that a court has ordered the extradition of a former head of state to be tried for gross human rights violations in his home country. The same organization had previously said that the conviction for genocide of Jean Kambanda, the former prime minister of Rwanda, in 1998, was historic; that the trial of Slobodan Miloevi, the former president of Yugoslavia, from 2001 to 2006, was ground-breaking; and that the trial of Charles Taylor, former president of Liberia, which started in late 2007, was a break with the past.

The reason why such trials are greeted as marking new events is that they are indeed part of a new trend towards military and judicial interventionism, and towards rule by supranational political and judicial institutions. In most cases, recent trials of heads of state have been conducted before those international or partly international tribunals which have proliferated since the end of the Cold War: the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY, created in 1993); the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR, created in 1994); the Special Court for Sierra Leone (created in 1996, which organized the trial of Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia, in The Hague); the International Criminal Court (ICC, created in 2002); and the Iraqi Special Tribunal (created by the American-run Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq in 2003). In other cases, recent trials or attempted trials of heads of state have had an important international component: General Pinochet, the former president of Chile, was arrested in London on an warrant issued by a judge in Spain who invoked universal laws against torture. (The attempted extradition was rejected on medical grounds and Pinochet 13 | 14 eventually returned to Chile, where he faced further legal procedures but died before ever coming to trial.) Meanwhile, former president Fujimori was extradited from Chile to Peru on a similar legal basis.