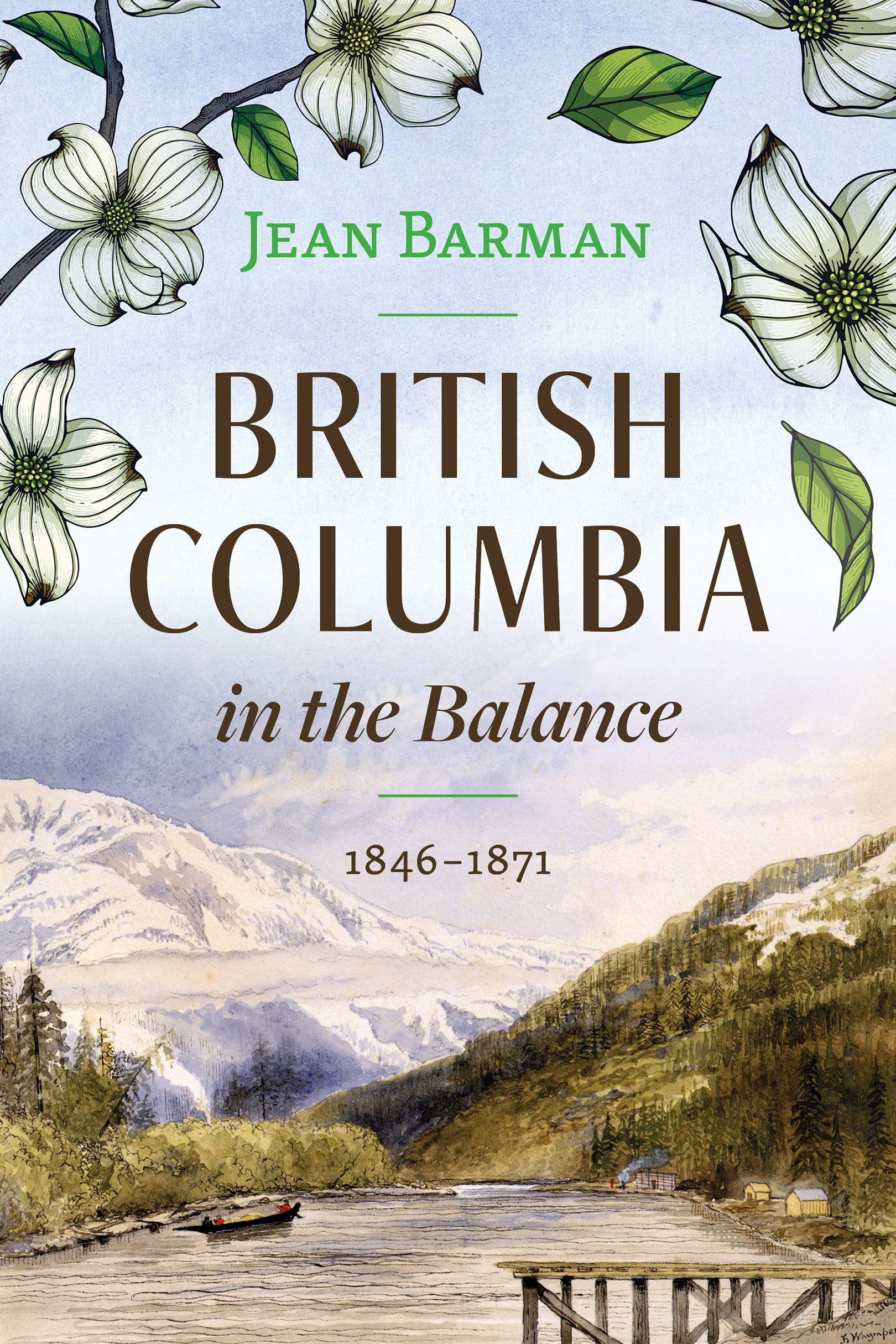

British Columbia in the Balance

Copyright 2022 Jean Barman

123452625242322

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, .

Harbour Publishing Co. Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC , V0N 2H0

www.harbourpublishing.com

Edited and indexed by Audrey McClellan

Text design by Carleton Wilson

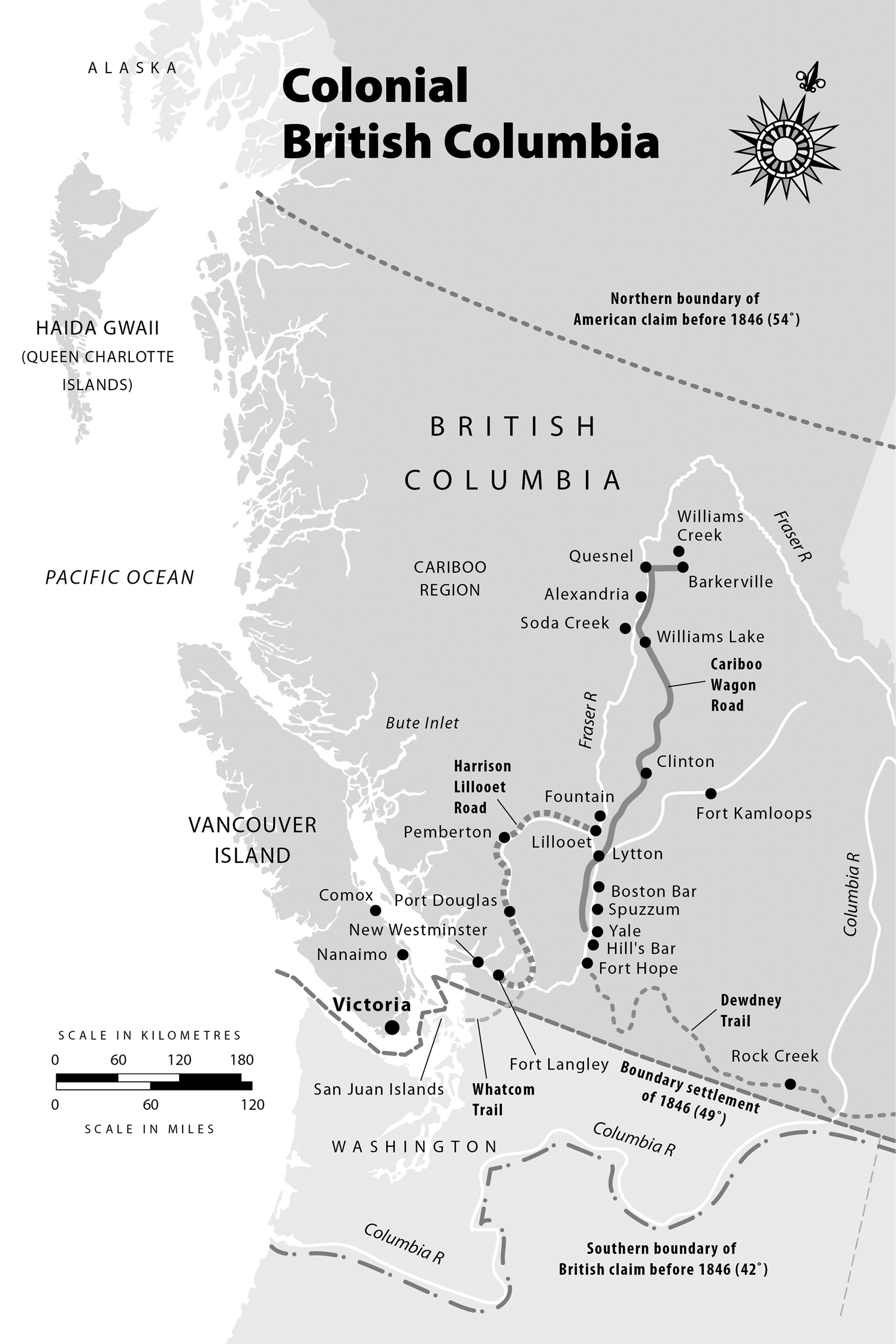

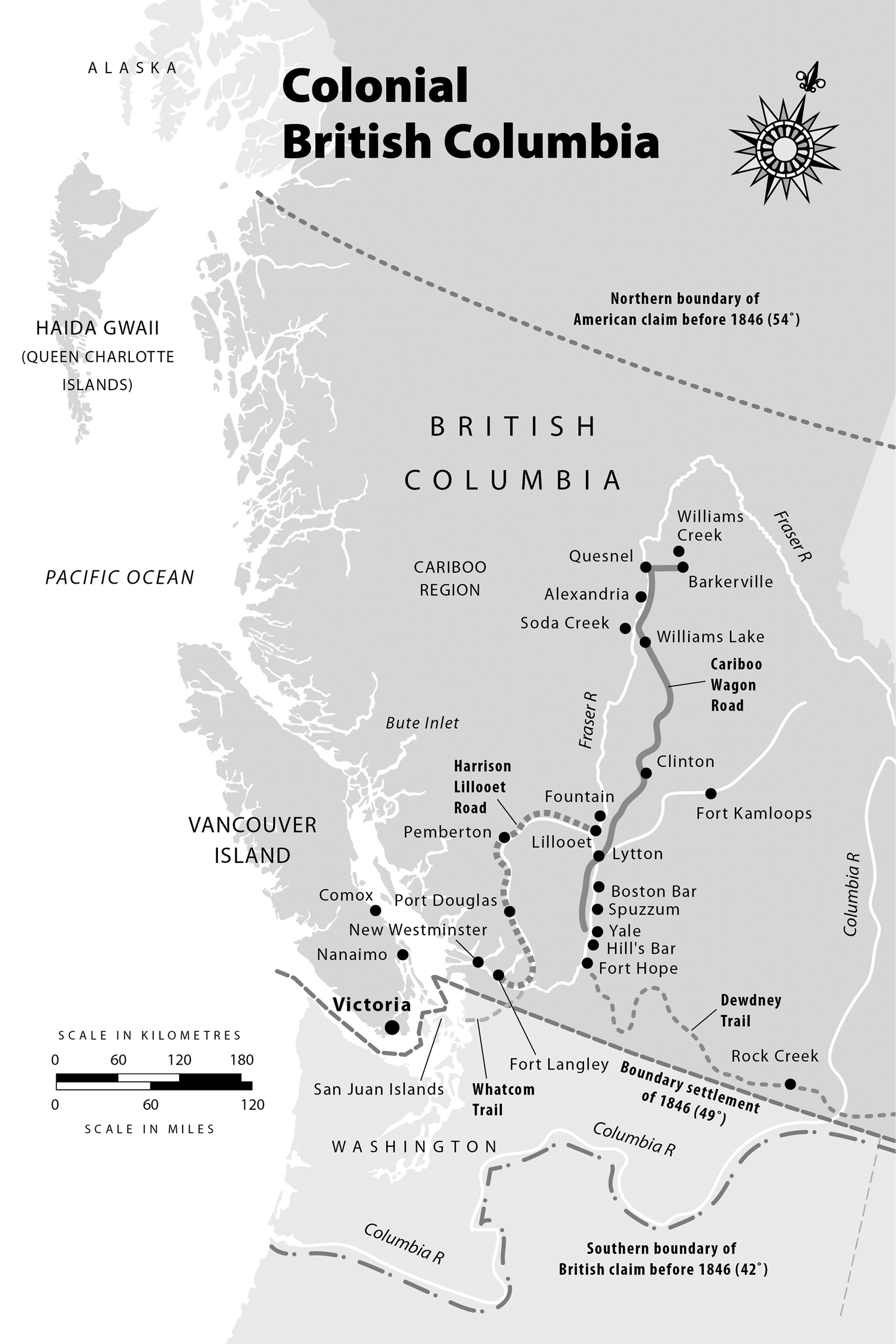

Map by Roger Handling / Terra Firma Digital Arts

Printed and bound in Canada

Harbour Publishing acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: British Columbia in the balance : 1846-1871 / Jean Barman.

Names: Barman, Jean, 1939- author.

Description: Includes index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20220249679 | Canadiana (ebook) 20220249709 | ISBN 9781550179880 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781550179897 ( EPUB )

Subjects: CSH : British ColumbiaHistory1849-1871. | CSH : British ColumbiaPolitics and government1849-1871.

Classification: LCC FC3822 .B37 2022 | DDC 971.1/02dc23

British Columbia in the Balance is dedicated to Donna Sweet, with whom I have spent more years than I can count searching out the history of British ColumbiaDonna to recover her familys story, myself its general complement.

Table of Contents

Map

Preamble Sensing the Past

For as long as I can remember, I have viewed British Columbia as a kind of promised land. Growing up in northwest Minnesota a few miles south of the Canadian border, I would, while waiting in the car for the school bus to arrive a half mile from my parents farm, listen to the weather forecast on Winnipeg radio, interspersed with my father once again musing on why, in emigrating from Sweden as a young man, he had not continued farther west to Saskatchewan or, better yet, to British Columbia. What deterred him, I came to realize, were the charms of my mother, who he had wooed during her holidays from teaching school, spent on her familys farm, half a mile from where my father had taken up land. It would be many years later, in a twist of fate, that my father had the opportunity to live out his dream of spending time in British Columbia after my husband accepted an academic position at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, where I later also taught.

My fathers dream has never left me. When our children were young, I conceived the idea of a popular history of British Columbia to appeal to newcomer families like our own, only to be summarily informed, on approaching a local historian for advice, that it was best for me as an outsider not to meddle in the history of British Columbians. Despite subsequently doing so time and again, I only recently came to realize the full extent to which I had, in my writing, possibly due to that earlier admonition as to whose history it was, ignored the provinces beginnings as a non-Indigenous place. Hence, I am only now so turning my attention.

To understand the critical quarter of a century between 1846, when Great Britain acquired the land base that would become todays British Columbia, and 1871, when that land base joined a newly formed Canadian Confederation, I not only probed known and recorded happenings but also peered beneath the surface of events. It was my good fortune to do so just as the primary source closest to the groundnamely, the private correspondence exchanged between the Colonial Office in London, which had charge of British colonies around the world (including what would become British Columbia) and those overseeing them on sitebecame accessible online thanks to University of Victoria historian James Hendrickson.

Reading the Colonial Office correspondence turned my attention to the formative role played by a gold rush that began on the British Columbia mainland in 1858a time when the future Canadian provinces non-Indigenous population was almost wholly linked to a trade in animal pelts. I quickly became aware that among the reasons British Columbia became a Canadian provincerather than an American state or states, despite its proximity to an expansive United Statesnone was more important from the top down than the leadership of long-time fur trader James Douglas on site and of the Colonial Office in faraway London. While the gold rush as such mattered to the course of events, so did miners sticking around rather than moving on once gold lost its lustre, due very possibly to their having partnered with local Indigenous women at a time when non-Indigenous women were a rarity. Just as James Douglas and the Colonial Office affected the course of events from the top down, such unions were fundamental in the years during which the future of British Columbia hung in the balance.

Those of us who peer beneath the surface of events have our own instances of happenchance. One of my most consequential originated with the head of the Anglican Archives at the University of British Columbia having some years earlier generously offered me, while I was researching another topic, a transcribed copy of the private journal kept by George Hills, founding bishop of the Church of England in British Columbia, from the time of his arrival in the colony in 1860. There, Hills jotted down on an almost daily basis what mattered to him in the everyday, giving us a perspective from the bottom up that might otherwise have been lost from view.

Reading through the journal, my search for understanding took on a life of its own. As one example among the many that intrigued me, on May 20, 1862, Bishop Hills described a recent event in the small gold rush town of Douglas, now Port Douglas:

Almost every man in Douglas lives with an Indian woman. The Magistrate Mr. Gaggin is not an exception from the immorality. Recently the constable Humphreys was ordered to a distance by the Magistrate. The Indian woman he lived with was named Lucy, by whom he had a child. He proposed to take her with him. The magistrate was for some reason opposed. [The constable asked,] May I depend upon your honour that she shall be safe during my absence. The magistrate promised such should be the case. He violated the promise & induced the woman to come to him. The constable was highly incensed on his return& at length quitted the situation.

What can we expect when the representatives of England thus deport themselves.

My response to this entry might have gone no further except for a chance encounter some years earlier. While researching another topic, I was introduced to a descendant of the child born to Humphreys and Lucy who, on learning of my interest in British Columbias history, and believing the time had come to do so, shared with me her familys version of the story, which I included in