2002 Modern Library Paperback Edition

Biographical note copyright 2002 by Random House, Inc.

Introduction copyright 2002 by David Quammen

Series introduction copyright 2002 by Jon Krakauer

Text illustrations copyright 1982 by Claire Van Vliet

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Modern Library, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

M ODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER Design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING - IN - PUBLICATION DATA

Hoagland, Edward.

Notes from the century before: a journal from British Columbia/Edward Hoagland.

p. cm.(Modern Library exploration)

Originally published: New York: Random House, 1969.

eISBN: 978-1-58836-224-7

1. British ColumbiaDescription and travel. 2. Hoagland, EdwardJourneysBritish Columbia. 3. PioneersBritish ColumbiaHistory. 4. Frontier and pioneer lifeBritish Columbia. 5. British ColumbiaSocial life and customs. I. Title. II. Series.

F1087 .H76 2002 917.11044dc21 2001056232

Modern Library website address:

www.modernlibrary.com

v3.1

I NTRODUCTION TO THE M ODERN L IBRARY E XPLORATION S ERIES

Jon Krakauer

Why should we be interested in the jottings of explorers and adventurers? This question was first posed to me twenty-five years ago by a skeptical dean of Hampshire College upon receipt of my proposal for a senior thesis with the dubious title Tombstones and the Mooses Tooth: Two Expeditions and Some Meandering Thoughts on Climbing Mountains. I couldnt really blame the guardians of the schools academic standards for thinking I was trying to bamboozle them, but in fact I wasnt. Hoping to convince Dean Turlington of my scholarly intent, I brandished an excerpt from The Adventurer, by Paul Zweig:

The oldest, most widespread stories in the world are adventure stories, about human heroes who venture into the myth-countries at the risk of their lives, and bring back tales of the world beyond men. It could be argued that the narrative art itself arose from the need to tell an adventure; that man risking his life in perilous encounters constitutes the original definition of what is worth talking about.

Zweigs eloquence carried the day, bumping me one step closer to a diploma. His words also do much to explain the profusion of titles in bookstores these days about harrowing outdoor pursuits. But even as the literature of adventure has lately enjoyed something of a popular revival, several classics of the genre have inexplicably remained out of print. The Modern Library Exploration Series is intended to rectify some of these oversights.

The eleven books we have selected for the series thus far span fifteen centuries of derring-do. All are gripping reads, but they also offer a fascinating look at the shifting rationales given by explorers over the ages in response to the inevitable question: Why would anyone willingly subject himself to such unthinkable hazards and hardships?

In the sixth century, according to medieval texts, an Irish monk known as Saint Brendan the Navigator became the first European to reach North America. Legend has it that he sailed from Ireland to Newfoundland in a diminutive boat sewn from leather hidesa voyage of more than 3,000 miles across some of the worlds deadliest seas, purportedly to serve God. The Brendan Voyage describes modern adventurer Tim Severins attempt to duplicate this incredible pilgrimage, in 1976, in an exact replica of Saint Brendans ancient oxhide vesselprofessedly to demonstrate that the monks journey was not apocryphal.

La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West, by the seminal nineteenth-century historian Francis Parkman, recounts the astonishing journeys of Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, as he crisscrossed the wilds of seventeenth-century America in hopes of discovering a navigable waterway to the orient. La Salle did it, ostensibly at least, to claim new lands for King Louis XIV and to get rich. He succeeded on both countshis explorations of the Mississippi Basin delivered the vast Louisiana Territory into the control of the French crownbut at no small personal cost: In 1687, after spending twenty of his forty-three years in the hostile wilderness of the New World, La Salle was shot in the head by mutinous members of his own party, stripped naked, and left in the woods to be eaten by scavenging animals.

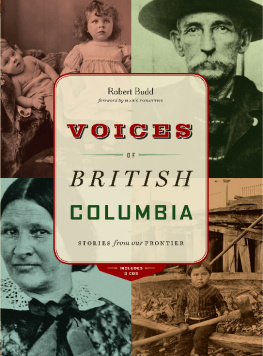

Francis Parkmans writing is distinguished by its richness, vitality, and acute sense of place. Exactly one hundred years after he published La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West, another incomparable prose stylist, Edward Hoagland, published Notes from the Century Before, an account of his travels through northern British Columbia in the summer of 1966. Hoagland journeyed to the periphery of the continent in order to document the last remnants of the North American frontier before it vanished altogether, and to meet the resolute old-timers who had first settled there.

In the first chapter of Notes, Hoagland explains that his visit to the Canadian backcountry was somewhat like looking at the Missouri Basin not so very long after Parkmans time. Im a novelist, not a historian, but at best Im a rhapsodist toothat old fashioned, almost anachronistic form. The rhapsodies that float across the pages of Hoaglands book describe a dreamlike landscape populated by an assortment of crusty, idiosyncratic characters not easily forgotten.

Speaking of books about singular characters, Weird and Tragic Shores, by Chauncey Loomis, tells the story of Charles Francis Hall, a flamboyant Cincinnati businessman and self-styled explorer who, in 1871, endeavored to become the first person to reach the North Pole. Hall, Loomis tells us, was impelled by a sense of personal destiny and of religious and patriotic mission, and displayed energy, will power, and independence remarkable even in a nineteenth-century American. He got closer to the pole than any Westerner ever had, but perished en route under mysterious circumstances and was buried so far north of the magnetic pole that the needle of a compass put on his grave points southwest. In 1968 Loomis journeyed to this distant, frozen grave, exhumed the corpse, and performed an autopsy that cast macabre new light on how Hall came to grief.

Farthest North is a first-person narrative by the visionary Norse explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who in 1893 set sail for the North Pole from Norway with a crew of twelve in a wooden ship christened the Fram, hoping to succeed where Hall and so many others had failed. Nansens brilliant plan, derided as crazy by most of his peers, was to allow the Fram to become frozen into the treacherous pack ice of the Arctic Ocean, and then let prevailing currents carry the icebound ship north across the pole. Two years into the expedition, alas, and still more than 400 miles from his objective, Nansen realized that the drifting ice was not going to take the Fram all the way to the pole. Unfazed, he departed from the ship with a single companion and provisions for 100 days, determined to cover the remainder of the distance by dogsled and on skis, with no prospect of reuniting with the Fram for the return journey. The going was slow, perilous, and exhausting, but they got to within 261 statute miles of the pole before giving up and beginning a desperate, yearlong trudge back to civilization.

Unlike La Salle, Hall and Nansen couldnt plausibly defend their passion for exploration by claiming to do it for utilitarian ends. The North Pole was an exceedingly recondite goal, a geographical abstraction surrounded by an expanse of frozen sea that was of no apparent use to anybody. Hall and Nansen proffered what had by then become the justification de rigueur for jaunts to the ends of the earthalmighty sciencebut it didnt really wash.