Madisons Militia

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Carl T. Bogus 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780197632222

eISBN 9780197632246

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197632222.001.0001

For William and Dov

Contents

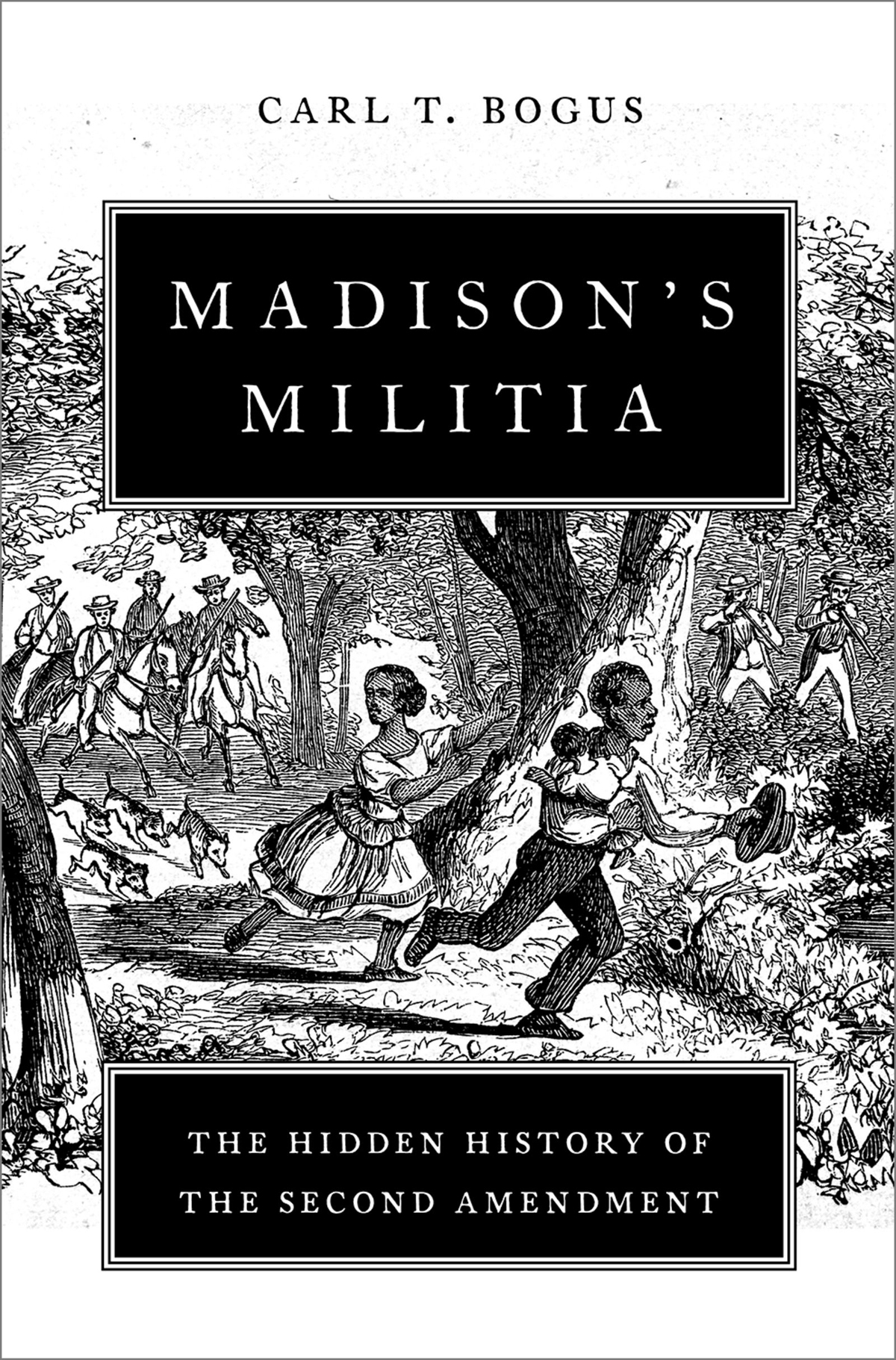

The nightmare turned real in the still-dark, early morning of Sunday, September 9, 1739, on the banks of the Stono River, about fifteen miles due west of Charleston (or as it was then called, Charles Town).

The armed band of slaves marched west on Pons Road. Some speculate they were heading for Spanish Florida. During the preceding year, Spain issued a royal edict promising freedom to escaped slaves who made their way to Florida. But Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, the northern outpost where Spain established a community of free Blacks, was about 275 miles away. If the slaves primary goal was to get there, one assumes they would have moved as quickly and surreptitiously as possible. That was not what they did. On eight occasions, they left Pons Road to invade the homes of plantation owners and other colonists. Once they were driven off; and once, a slave hid his master and told the rebels he was not at home. The rebels pillaged the other six houses, set them ablaze, and killed everyone insidea body count totaling forty slave owners and family members before the day was through.

The targets were not indiscriminate. The rebels attacked the home of the largest plantation owner in the area, and those of two other major plantation owners, too; but they passed by the home of at least one other very large plantation owner. They attacked the homes of two justices of the peace; but when they passed Wallaces Tavern, they left the proprietor alone because, they said, he was a good man and kind to his slaves.

We can confidently conclude the rebels were not trying to reach freedom in Spanish Florida because they did not try to conceal their whereabouts. Just the opposite: They beat drums, flew banners, and called out Liberty! to other slaves, exhorting them to join the insurrection. Their ranks swelled to somewhere between sixty and one hundred. They had come from eight different plantations.

No one knows how large the rebellion would have grown if not for a bizarre coincidence. A group of five White men, on their way to Charleston for the South Carolina Assemblys new legislative session, happened to ride within eyesight of the rebels. One member of the group was Dr. William Bull II, the lieutenant governor of South Carolina and one of the provinces officials most concerned about the potential for slave insurrections. In a letter just four months earlier, Bull had warned that the colonys Negroes, which were their chief support, may in little time become their enemies, if not their masters, and that One can only imagine Bulls horror as he saw a sizable group of armed slaves in open rebellion.

Bull spurred his horse on to the Presbyterian Church at Wiltown Bluff, a couple of miles south, where Sunday services were in progress. A few weeks earlier, the Assembly had passed the Security Act, which required all White males who were responsible for bearing arms in the militiathat meant all able-bodied White men between the ages of sixteen and sixtyto take guns and ammunition with them to church on Sundays and on Christmas. While the Security Act would not formally take effect for three more weeks, planters hardly needed the penalty of a fine to stimulate compliance. This was, after all, exactly the eventuality they long feared. When Bull arrived at the church, therefore, an armed contingent of militia was already there.

Leaving frightened women and children at the church, the men rode off in pursuit of the rebels. By four oclock in the afternoon, perhaps as many as one hundred armed and mounted militiamen, led by Captain John Bee, found the slaves in an open field about ten miles southwest of where the lieutenant governor had spotted them earlier. They dismounted and attacked the rebels on foot.

Had the Stono rebels harbored some hopeeven just a glimmerthat the rebellion would be large enough to repel the inevitable counterattack by the militia and somehow survive? Maybe; desperate people will believe what they must. But in their hearts, they must have known that was unrealistic. Even if the rebellion had become large enough, and well-armed enough, to repel the first assaults, militia would come from further and further awayfrom all of the South Carolina Low Country, from farther-flung areas in western South Carolina, from Georgia and from North Carolina, too, until the rebellion was destroyed. The word of the rebellion would spread among Whites faster than among enslaved Blacks because Whites had horses. And the Whites would show no mercy. All the rebels could reasonably hope for was to kill as many Whites as possible before they themselves died free. The Stono Rebellion was, in short, a suicide mission.

None of this was lost on the White population. As historian Peter Charles Hoffer observed, after the Stono Rebellion no White could ever fool himself or herself again that slaves were content in their chains.

There had, however, been fears of slave uprisings in South Carolina long before the Stono Rebellion. In 1734, a visitor to the colony recorded in his diary that slaves are generally thought to watch [for] an opportunity of revolting against their masters, as they have lately done in the islands of St. John and St. Thomas. Prior to Stono, South Carolina had an extensive slave patrol system. Groups of five men, led by Captains of Patrol, made regular rounds, usually on horseback, to stop and question slaves who were not where they should be, ensure that groups of slaves were not meeting or assembling, search slave quarters for weapons and other contraband, and administer punishmentsfrom whippings to hangingsto slaves violating the rules.

Slave patrols were considered so essential to the security of the colony that patrollers were authorized to enter plantations, conduct inspections, and mete out punishments without the consent of plantation and slave owners. Men who volunteered for patrol duty were excused from militia drills. But Stonothen the largest slave rebellion on the American mainlandcaused South Carolina and the South as a whole to heighten slave control measures. The South Carolina legislature directed that for at least three months, or until all of the Stono rebels were captured, completely armed militia patrol both banks of the Stono River every night.