A SLAVE

in the

WHITE HOUSE

A SLAVE

in the

WHITE HOUSE

PAUL JENNINGS AND THE MADISONS

Elizabeth Dowling Taylor

with

Foreword by Annette Gordon-Reed

and

A Colored Mans Reminiscences of James Madison

by Paul Jennings

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated to

Luke Taylor,

my son and inspiration.

I AM A PROUD AMERICAN

14 February 1960

I have every reason to be proud of being an American. My ancestors contributed so much to make this country what it is today. They fought to give America its freedom, even gave their lives. They have done the same in every war since. Thus, they have helped to preserve America. They nursed it in its infancy and for two centuries sweated and suffered as slaves to lay the foundation of its great wealth. Today, we find ourselves on the threshold of a new era ushering in the type of freedom for all for which my fore-parents sacrificed so much.

C. Herbert Marshall, M.D.

Dr. Herbert Marshall was the great-grandson of Paul Jennings. His statement for I Am a Proud American Day was published in the Negro History Bulletin, organ of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, in 1960. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (www.asalh.org).

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IT IS A PLEASURE TO ACKNOWLEDGE THOSE COLLEAGUES and friends who generously gave of their time and expertise in reviewing part or all of the manuscript: Catherine Allgor, Andrew Burstein, Bruce Carveth, Breena Clark, Amy Larrabee Cotz, William Freehling, Ralph Ketcham, David Mattern, Drew McCoy, Matthew Reeves, Mary Kay Ricks, Leni Sorensen, Lucia Stanton, John Taylor, and Marsha Williamson. I have benefited immeasurably from their comments. Any errors of fact or interpretation that remain are mine alone.

The research that the book is based on was facilitated by support from a number of institutions. At the Montpelier Foundation, I extend my appreciation to president Michael Quinn, board members Elinor Farquhar, Greg May, Hunter Rawlings, and Roger Wilkins, and staff members Thomas Chapman, Christian Cotz, and Peggy Vaughn. At the National Trust for Historic Preservation, I am especially grateful to Max van Balgooy, and at the White House Historical Association, to Neil Horstman and John Riley. I also thank White House curator William Allman. Other individuals who supported this work with information, discussion, or encouragement include Will Harris, Lee Langston-Harrison, Deborah Lee, David Levering Lewis, Betty Monkman, Peter Onuf, Carla Peterson, Kym Rice, Holly Shulman, Susan Stahlberg, Karen Williams, and Michael R. Winston.

Many long days searching archives at various research facilities were rewarded by fellowship among researchers, and I particularly recognize Barbara Bates, Mary Belcher, Susan Borchardt, John Sharp, Doreen Stevens, and Beverly Veness. I acknowledge, too, the kind assistance from staff members Jeffrey Flannery and Julie Miller at the Library of Congress, Robert Ellis at the National Archives and Records Administration, William Branch and Ali Rahmann at the District of Columbia Archives, and Yvonne Carignan at the Historical Society of Washington, DC.

Over the final six months of writing this book, I was generously supported by a fellowship through the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities at the University of Virginia. I am grateful to Margaret Jordan, Mary Alexander, and all the donors who made the fellowship possible, and to the foundations president, Robert Vaughn.

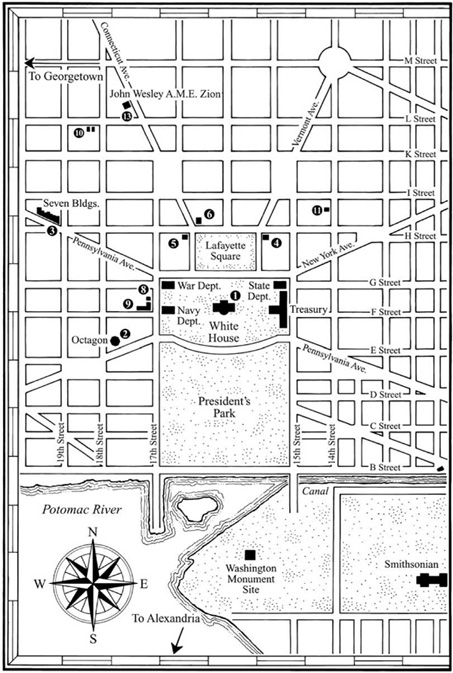

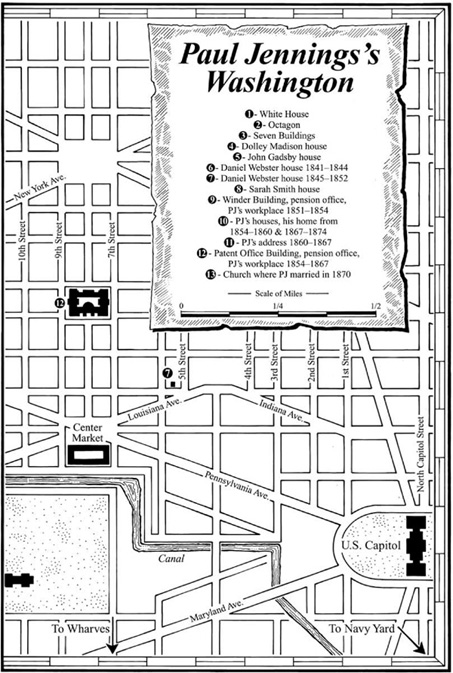

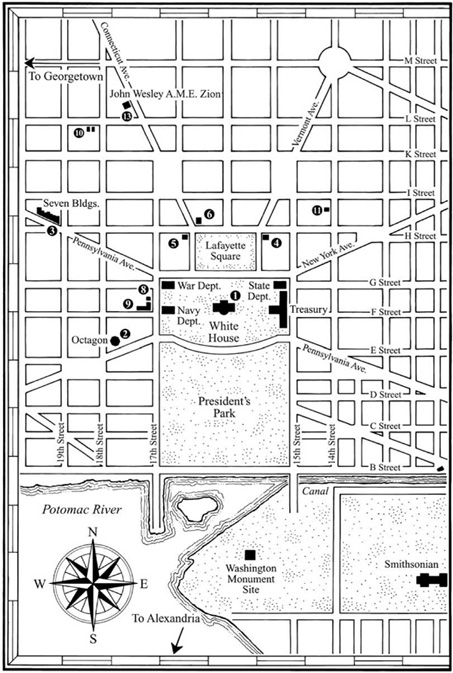

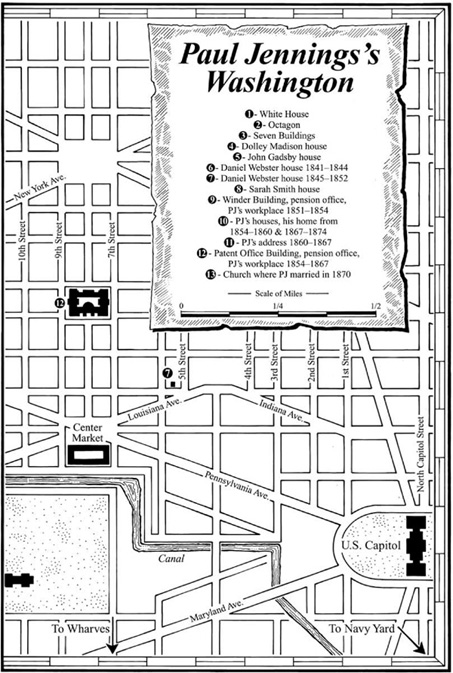

Thanks to my literary agent, Michelle Tessler, and to Palgrave Macmillan assistant editor Isobel Scott for steering me through the publication process. I am very grateful to Annette Gordon-Reed for the thoughtful foreword that opens the book and to Rick Britton for the original maps and other graphics that illustrate it.

Last, I thank from the heart two familiesmy own and the Jennings familyfor the steadfast support and encouragement that has sustained me through this long labor of love. Forever indebted, I am fondly yours.

FOREWORD

ANONYMITY IS THE USUAL FATE OF THE MILLIONS OF people who were enslaved in America during the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. With no access to legalized marriage and family life, no right to make contracts or enter into business relationships, American slaves rarely entered the public record of their own accord. Instead, they more often entered as property: the subject of sales, division of estates, and, in extreme cases, when they were participants in criminal cases. They do, of course, appear in private documents. The family letters of slave owners refer to the enslaved, very often those who served in the household and were closely involved in the day-to-day life of the masters and mistresses and their children. The business of slavery also required compiling lists of the names and configurations of families as slave owners kept track of the human beings over whom they exercised power. While the family letters of slave owners and their inventories of their human property can sometimes give us clues and starting points for considering the lives of the enslaved, they do not begin to get at the complexity of lives lived in bondage. For the most part, the feelings, thoughts, and yearnings of the enslaved will remain hidden under the blanket oppression of the slave system. Their own assessments of the people who enslaved them and other whites are also extremely rare. Every now and then a few people, because of circumstances and fortuitous timing, were able to escape the shroud of anonymity. Paul Jennings was just such a person.

The circumstances: Paul Jennings was born in 1799 at Montpelier, the Virginia plantation of James Madison. Madison had been on the national scene for over a decade as a legislator in the state and national governments and as one of the principal shapers of the United States Constitution. Jennings was mixed race; his mother was of African and Indian ancestry, his father an Englishman. It was not the rule, but it was frequently the case that mixed-raced enslaved people served within the household at Virginia plantations. They were maids to the mistresses of plantations, child companions/minders to the white children of the owners, and valets to the masters of the house. This type of proximity is often characterized as a form of privilege. But the story told in the pages of this book shows that it was a mixed privilege at best. Proximity to slave owners meant being more directly subject to their needs, both whimsical and serious. Also, when members of the family traveled, their enslaved servants had to travel with them, whether they wanted to or not.

Next page