TABLE OF COLOUR PLATES

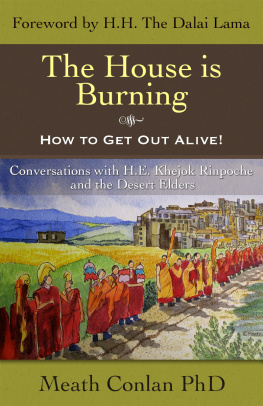

Cover: Sketch showing the monks of Dhe-Tsang welcoming their Abbot back into the monastic community (Meath Conlan, 2013).

Note: All colour plates are taken from original sketches by the author Meath Conlan, Perth, 1997 and 2013 who himself made field notebook sketches and photographs during his several visits to Tibet.

The following parable, ascribed to the Buddha, tells of children who are in great danger in a house which is on fire.

One day, a fire broke out in a wealthy mans house. He shouted at his children to flee the fire! But they were absorbed in their games. They refused to heed his warning.

Their father was desperate. Then he called out to them, Listen! Outside here I have carts full of amazing toys! He knew that hearing this would be irresistible to his children.

Without a second thought they rushed outside to play with the new toys. But instead of the carts that he had promised, he gave them a cart draped with precious stones and pulled by massive white bullocks. The important thing, their father thought, is that my children are saved from the dangers of the fire.

In this parable the father represents the Buddha. Human beings are the children trapped in the burning house. The house represents the world burning with fires: such as old age, sickness and death. The cart filled with precious stones symbolises true happiness. What the Buddha teaches is like the father getting his children to leave their toys for what is really important in life.

The use of stories to convey an essential truth or insight is honoured in many spiritual and cultural traditions. The Desert Elders were practical. They told stories with a hard-edge and a point to them. With little or no training in theology, they preferred the simplicity of their own experience, based on faith and the quiet reading of the scriptures. Their simplicity and grounded common-sense cut through mere intellectual learning. For those who came into the wilderness seeking understanding, their advice was mostly brief and to the point, focusing on the immediate issues and problems of daily life. Over time, the sayings of these Elders were gathered and recorded. These treasures of spirituality continue to have a wide readership among Christians today, for they have a universal appeal that speaks to everyone seeking insight for the journey home.

Once upon a time, one of the younger brothers visited a desert Elder who sat amid a small group of people who were quietly at prayer and work. The young man said to the Elder, I have the ability to walk on water! After a pause, he continued, Why dont we go to the middle of the small lake over there, and have a spiritual discussion?

But the Elder replied, If what you are really trying to do is get away from these people, I suggest you simply come with me and fly into the air. We can drift along in the quiet of the open sky. We can talk better there.

The younger man replied, But I cant do that. The power you speak of is not one that I possess.

Then the Elder responded, Exactly! Your power of remaining still on the surface of the water is also possessed by fish. And my ability of floating through the air can be performed by any fly. These abilities have nothing to do with what really matters. In fact, they may become a source of arrogance and competitiveness, but not spirituality. If you and I are going to talk of spiritual matters, we should really be talking right here.

Having often visited Khejok Tulku Rinpoche, I discovered a treasure-trove in his short sayings. A student of Rinpoches, Thomas Lim of Hong Kong had, some years earlier, collected his succinct instructions for life. They resonate with wisdom that may be applied by people seeking practical spiritual encouragement in ordinary, everyday life. When I read Rinpoches words, I was impressed by their similarity to those sayings passed down to us through the Western Christian tradition from the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, Persia and Syria and known as the verba Seniorum, the Sayings of the Elders.

In writing this anthology, my goal was to present the two sources of teaching, one from a senior practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism, and the other from the Christian Desert Tradition, as a sensitive contribution to inter-religious dialogue. Re-reading the Desert Fathers has, for me, been a source of re-invigoration and delight. But reading them with a view to showing the common ground, which at the deepest level of experience exists between people of different religious traditions, has been exciting and rewarding. Once having selected Rinpoches sayings, I organised them into four main themes. These touch on perennially evocative subjects in human life: finding peace of mind, the experience of anger and with what mind to address it, the necessity of developing wisdom and compassion, and finally, the consideration of death, especially ones own. It has not been my intention to offer lengthy commentaries of what Rinpoche and the Desert Fathers have said. Rather, following a brief introduction, I simply record the sayings from two traditions: Christian and Buddhist. The sayings you read here will speak for themselves, and so, I trust, provide spiritual refreshment for the journey.

I offer my thanks to Thomas Garvey the owner of Templegate Publishers whose encouragement it was that led me to write this collection of stories from the Desert Elders and Buddhist Traditions. I wish also to thank my mother Nancy who has provided me with invaluable assistance as my tireless reader. Her insights and grasp of the English language has improved the quality and depth of the work incalculably. Finally, my appreciation is also due to His Eminence Khejok Tulku Rinpoche, whose practical wisdom and compassion for all, first gave me the idea of composing this book as an inter-spiritual adventure. Rinpoche encouraged me in writing this book, as a way of showing how the lives and spiritual wisdom of some third and fourth century hermits, together with the teachings and experience of a Tibetan Buddhist master of the twenty-first century can harmonise on common ground.

Meath Conlan, Ph.D. Perth, January 5 2013

Khejok Rinpoche: The advice I offer is of no benefit unless you make it a part of yourself by familiarisation. It must be etched into your heart and not merely as words recalled to mind. When you have accomplished this, your actions, thoughts, and speech will reflect those qualities [of which I speak]. Even unconsciously, every single word you utter, every gesture you make, will be your teaching to the world, and the world will benefit, just by your mere presence.

Desert Saying: It is said of Abba Ammonas that his goodness was so indelibly etched into his character that he took no notice of wickedness in others. Once upon a time a group of old men brought him a young woman who was pregnant. They called her a wretch and demanded Ammonas give her a severe penance. He, however, marked her womb with the sign of the cross. He then commanded that six pairs of fine linen sheets be given her. He said, It is for fear that when she comes to give birth, either she or the child will die, and they will have nothing for the burial. But her accusers remonstrated, saying, Why did you do that Abba? Give her a punishment! But he turned, looked at them, and said, Look here my brothers, she is near death; what am I to do? After that no old man dared accuse anyone any more.

Next page