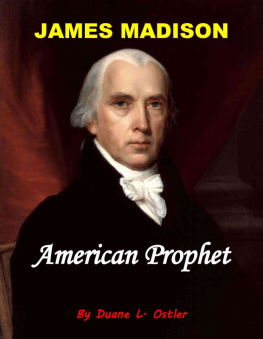

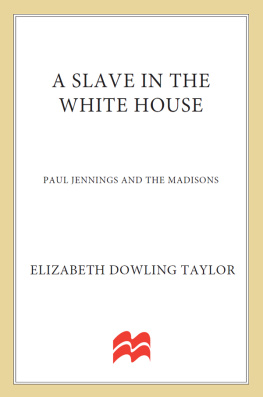

Among the laborers at the Department of the Interior is an intelligent colored man, Paul Jennings, who was born a slave on President Madisons estate, in Montpelier, Va., in 1799. His reputed father was Benj. Jennings, an English trader there; his mother, a slave of Mr. Madison, and the grand-daughter of an Indian. Paul was a body servant of Mr. Madison, till his death, and afterwards of Daniel Webster, having purchased his freedom of Mrs. Madison. His character for sobriety, truth, and fidelity, is unquestioned; and as he was a daily witness of interesting events, I have thought some of his recollections were worth writing down in almost his own language.

On the 10th of January, 1865, at a curious sale of books, coins and autographs belonging to Edward M. Thomas, a colored man, for many years Messenger to the House of Representatives, was sold, among other curious lots, an autograph of Daniel Webster, containing these words: I have paid $120 for the freedom of Paul Jennings; he agrees to work out the same at $8 per month, to be furnished with board, clothes, washing, etc.

J. B. R.

About ten years before Mr. Madison was President, he and Colonel Monroe were rival candidates for the Legislature. Mr. Madison was anxious to be elected, and sent his chariot to bring up a Scotchman to the polls, who lived in the neighborhood. But when brought up, he cried out: Put me down for Colonel Monroe, for he was the first man that took me by the hand in this country. Colonel Monroe was elected, and his friends joked Mr. Madison pretty hard about his Scotch friend, and I have heard Mr. Madison and Colonel Monroe have many a hearty laugh over the subject, for years after.

When Mr. Madison was chosen President, we came on and moved into the White House; the east room was not finished, and Pennsylvania Avenue was not paved, but was always in an awful condition from either mud or dust. The city was a dreary place.

Mr. Robert Smith was then Secretary of State, but as he and Mr. Madison could not agree, he was removed, and Colonel Monroe appointed to his place. Dr. Eustis was Secretary of Warrather a rough, blustering man; Mr. Gallatin, a tip-top man, was Secretary of the Treasury; and Mr. Hamilton, of South Carolina, a pleasant gentleman, who thought Mr. Madison could do nothing wrong, and who always concurred in everything he said, was Secretary of the Navy.

Before the war of 1812 was declared, there were frequent consultations at the White House as to the expediency of doing it. Colonel Monroe was always fierce for it, so were Messrs. Lowndes, Giles, Poydrass, and Popeall Southerners; all his Secretaries were likewise in favor of it.

Soon after war was declared, Mr. Madison made his regular summer visit to his farm in Virginia. We had not been there long before an express reached us one evening, informing Mr. M. of Gen. Hulls surrender. He was astounded at the news, and started back to Washington the next morning.

After the war had been going on for a couple of years, the people of Washington began to be alarmed for the safety of the city, as the British held Chesapeake Bay with a powerful fleet and army. Everything seemed to be left to General Armstrong, then Secretary of war, who ridiculed the idea that there was any danger. But, in August, 1814, the enemy had got so near, there could be no doubt of their intentions. Great alarm existed, and some feeble preparations for defence were made. Com. Barneys flotilla was stripped of men, who were placed in battery, at Bladensburg, where they fought splendidly. A large part of his men were tall, strapping negroes, mixed with white sailors and marines. Mr. Madison reviewed them just before the fight, and asked Com. Barney if his negroes would not run on the approach of the British? No sir, said Barney, they dont know how to run; they will die by their guns first. They fought till a large part of them were killed or wounded; and Barney himself wounded and taken prisoner. One or two of these negroes are still living here.

Well, on the 24th of August, sure enough, the British reached Bladensburg, and the fight began between 11 and 12. Even that very morning General Armstrong assured Mrs. Madison there was no danger. The President, with General Armstrong, General Winder, Colonel Monroe, Richard Rush, Mr. Graham, Tench Ringgold, and Mr. Duvall, rode out on horseback to Bladensburg to see how things looked. Mrs. Madison ordered dinner to be ready at 3, as usual; I set the table myself, and brought up the ale, cider, and wine, and placed them in the coolers, as all the Cabinet and several military gentlemen and strangers were expected. While waiting, at just about 3, as Sukey, the house-servant, was lolling out of a chamber window, James Smith, a free colored man who had accompanied Mr. Madison to Bladensburg, galloped up to the house, waving his hat, and cried out, Clear out, clear out! General Armstrong has ordered a retreat! All then was confusion. Mrs. Madison ordered her carriage, and passing through the dining-room, caught up what silver she could crowd into her old-fashioned reticule, and then jumped into the chariot with her servant girl Sukey, and Daniel Carroll, who took charge of them; Jo. Bolin drove them over to Georgetown Heights; the British were expected in a few minutes. Mr. Cutts, her brother-in-law, sent me to a stable on 14th street, for his carriage. People were running in every direction. John Freeman (the colored butler) drove off in the coachee with his wife, child, and servant; also a feather bed lashed on behind the coachee, which was all the furniture saved, except part of the silver and the portrait of Washington (of which I will tell you by-and-by).

I will here mention that although the British were expected every minute, they did not arrive for some hours; in the meantime, a rabble, taking advantage of the confusion, ran all over the White House, and stole lots of silver and whatever they could lay their hands on.

About sundown I walked over to the Georgetown ferry, and found the President and all hands (the gentlemen named before, who acted as a sort of body-guard for him) waiting for the boat. It soon returned, and we all crossed over, and passed up the road about a mile; they then left us servants to wander about. In a short time several wagons from Bladensburg, drawn by Barneys artillery horses, passed up the road, having crossed the Long Bridge before it was set on fire. As we were cutting up some pranks a white wagoner ordered us away, and told his boy Tommy to reach out his gun, and he would shoot us. I told him he had better have used it at Bladensburg. Just then we came up with Mr. Madison and his friends, who had been wandering about for some hours, consulting what to do. I walked on to a Methodist ministers, and in the evening, while he was at prayer, I heard a tremendous explosion, and, rushing out, saw that the public buildings, navy yard, ropewalks, etc., were on fire.

Mrs. Madison slept that night at Mrs. Loves, two or three miles over the river. After leaving that place she called in at a house, and went upstairs. The lady of the house learning who she was, became furious, and went to the stairs and screamed out, Miss Madison! if thats you, come down and go out! Your husband has got mine out fighting, and d-- you, you shant stay in my house; so get out! Mrs. Madison complied, and went to Mrs. Minors, a few miles further, where she stayed a day or two, and then returned to Washington, where she found Mr. Madison at her brother-in-laws, Richard Cutts, on F street. All the facts about Mrs. M. I learned from her servant Sukey. We moved into the house of Colonel John B. Taylor, corner of 18th street and New York Avenue, where we lived till the news of peace arrived.