Max Hastings - The Korean War

Here you can read online Max Hastings - The Korean War full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1988, publisher: Simon & Schuster, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Korean War

- Author:

- Publisher:Simon & Schuster

- Genre:

- Year:1988

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Korean War: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Korean War" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Korean War — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Korean War" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To

Charlotte

Contents

List of illustrations

PLATES

2. Key international figures in the Korean crisis:

38. Artillery in action:

40. Behind the lines:

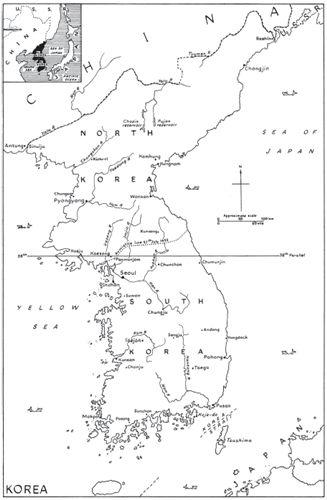

MAPS

Foreword

In the past twenty years, the public fascination with military history has become a minor literary phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic. It has centred overwhelmingly upon the Second World War. Indeed, at the extremities of the popular market, perceptions of the struggle between the Western Allies and the Germans long ago parted company with reality, and took on the mantle of fantasy borne a generation earlier by cowboys and indians. In the past decade, more surprisingly, Vietnam has also given birth to a major publishing industry. Some new books seek seriously to examine why the United States lost that war. Others, like the films they inspire, attempt to rewrite history, to present aspects of that sordid, doomed struggle in an heroic light.

How is it, then, that the other great mid-twentieth-century conflict with communism, Korea, remains so neglected? Popular awareness of the Korean War today centres upon the television comedy show M.A.S.H ., which dismays most veterans because it projects an image of Korea infinitely less savage than that which they recall. The United Nations suffered 142,000 casualties in the war to save South Korea from communist domination. The Koreans themselves lost at least a million people. United States losses in three years were only narrowly outstripped by those suffered in Vietnam over more than ten. Korea cost the British three times as many dead as the Falklands War. Chinese casualties remain uncertain, perhaps even in Peking, but they run into many hundreds of thousands. Since 1945, only the Cuban missile crisis has created a greater risk of nuclear war between East and West. As some recent scholarly researchers have pointed out, notable among them Dr Rosemary Foot in her fascinating The Wrong War , in Korea the American military displayed a far greater private enthusiasm for using atomic weapons against the Chinese than the Western world perceived, even a generation later. Korea remains the only conflict since 1945 in which the armies of two great powers for surely Chinas size confers that title have met on the battlefield.

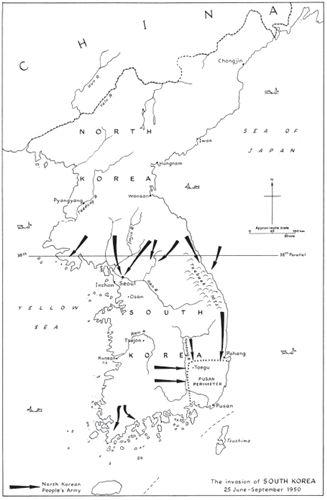

Many Westerners were happy to forget Korea for a generation after the war ended, soured by the taste of costly stalemate, robbed of any hint of glory. Yet consider the extraordinary cast of American characters that came together to determine the fate of that barren Asian peninsula: Truman and Acheson, Marshall and Mac- Arthur, Ridgway and Bradley. Then add the succession of great military dramas the destruction of Task Force Smith, the defence of the Pusan Perimeter, Inchon, the drive to the Yalu, the shattering winter advance of the Chinese. A host of lesser epics followed, which may be allowed to include the stand of the British 29 Brigade on the Imjin in April 1951, an action relatively minor in scale, yet the ferocity of which caught the imagination of the world. The fascination of Korea centres, more than anything, upon the battlefield confrontation between the armies of China and the United States. But the tragedy of the Korean people, the principal sufferers in the three-year struggle across their land, deserves far greater attention than it has been granted.

Above all, perhaps, Korea merits close consideration as a military rehearsal for the subsequent disaster in Vietnam. So many of the ingredients of the Indochina tragedy were already visible a decade or two earlier in Korea: the political difficulty of sustaining an unpopular and autocratic regime; the problems of creating a credible local army in a corrupt society; the fateful cost of underestimating the power of an Asian communist army. For all the undoubted benefits of air superiority and close support, Korea vividly displayed the difficulties of using air power effectively against a primitive economy, a peasant army. The war also demonstrated the problem of deploying a highly mechanised Western army in broken country, against a lightly equipped foe. Many of the American professional soldiers who served under MacArthur or Ridgway did so later under Westmoreland or Abrams. When they reminisce about the campaigns of 195053, it is striking how frequently slips of the tongue cause them to substitute Vietnam for Korea in their conversation.

Yet because it proved possible finally to stabilise the battle in Korea on terms which allowed the United Nations or more realistically, the United States to deploy its vast firepower from fixed positions, to defeat the advance of the massed communist armies, many of the lessons of Korea were misunderstood, or not learned at all. For instance, Pentagon studies showed during Korea, just as they had during World War II, that it was Americas lower socio-economic groups which bore the chief burden of fighting the war, and above all of filling the ranks of the infantry. Yet the same phenomenon would recur in Vietnam, and the serious shortcomings of the American footsoldier the man at the tip of the spear would once more have critical consequences. In Korea, the communists enjoyed the opportunity to learn a great deal about the limits of Western patience, the difficulties of maintaining popular enthusiasm for an uncertain cause in a democracy. By the time the armistice was signed at Panmunjom in August 1953, after a mere three years of hostilities, the Western Allies had become desperate to extricate themselves from a thankless war that offered so little prospect of glory or clear-cut victory. Yet in Korea, the communists had provided the most ruthlessly simple casus belli , the most incontrovertible provocation by aggression, to be offered to the West at any period between 1945 and this time of writing.

As in my past books, I have sought to explore the Korean War through a combination of personal interviews with surviving participants, and archival research in London and Washington. In the course of writing it, I have met more than two hundred American, Canadian, British, and Korean veterans of the conflict. Perhaps the most exciting aspect of my research has been the opportunity to talk to Chinese veterans, granted to me in 1985 through the good offices of the Peking Institute of Strategic Studies, and the help of the late and much-lamented Colonel Jonathan Alford of the International Institute of Strategic Studies in London. One of the possibilities that first attracted me to the project was that, in the new mood of dtente between China and the West, it might be possible to gain some access to a Peking perspective upon the Korean War. After months of discussion and correspondence, this indeed proved to be so.

There are no German or Japanese triumphal museums commemorating World War II. It is an eerie experience for a Westerner to walk through the great halls of the Peking Military Museum, gazing upon the trophies of captured British bren guns and regimental flashes, American .50 calibre machine guns, helmets and aircraft remains. Yet if my visit was a measure of how much has changed between China and the West, it was also a reminder of how much remains the same. There is still a great display given over to Americas supposed 1952 bacteriological warfare campaign against North Korea. China claims to have inflicted 1,090,000 casualties on the US armed forces in Korea, a figure one assumes was arrived at by adding a few thousands to the total Chinese casualties claimed by the US. I spent some fascinating days and nights in Peking and Shanghai, listening to Chinese veterans describing their battlefield experience in Korea. Yet it must be said that none deviated for a moment from strict Party orthodoxy in describing their enthusiasm for the war, and satisfaction with the manner in which it was conducted. There is no comparison with the experience of interviewing British and American veterans, whose views reflect such a wide and forthright range of opinion. In Peking, senior officers gave me some fascinating explanations of Chinese behaviour. At their Command and Staff College, I gained some glimpses of the PLAs military perspective upon various battles. But there remains, of course, no opportunity to check official assertions against archives or written evidence. In a totalitarian state, such as China remains, it is debatable whether even those at the summit of power can discover the historical truth about events in the recent past, even should they wish to do so. In the same fashion, when Mr Gorbachev claims in a speech that the Soviet Union won the Second World War effectively unaided, it seems rash to assume that he is perpetrating a conscious untruth. It may yet be that he, like the vast majority of his people, simply does not know any better.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Korean War»

Look at similar books to The Korean War. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Korean War and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.