J ACOB R. M ECKLENBORG

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Jacob R. Mecklenborg

All rights reserved

First published 2010

Second printing 2011

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.191.2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mecklenborg, Jake.

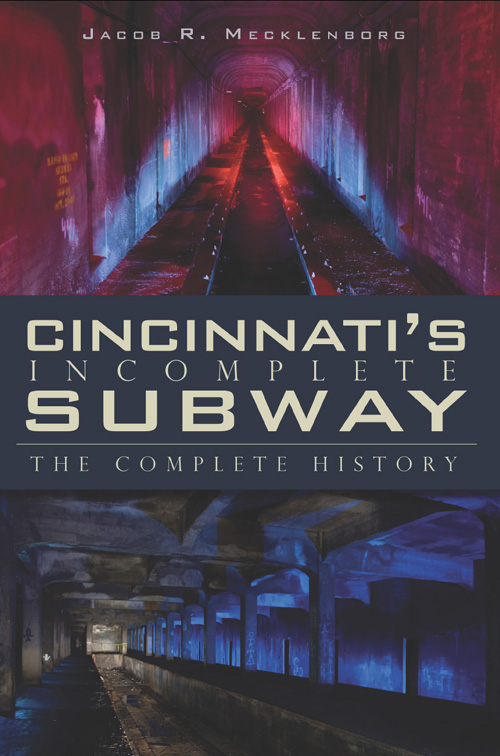

Cincinnatis incomplete subway : the complete history / Jake Mecklenborg.

p. cm.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-895-8

1. Subways--Ohio--Cincinnati--History. 2. Subways--Ohio--Cincinnati--Design and construction--History. 3. Local transit--Ohio--Cincinnati--History. 4. City planning--Ohio--Cincinnati--History. 5. Cincinnati (Ohio)--History. 6. Cincinnati (Ohio)--Social conditions. 7. Cincinnati (Ohio)--Economic conditions. I. Title.

HE4491.C552M43 2010

388.4280977178--dc22

2010037826

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

Summer 1920 view of drained canal and Section One subway work. Courtesy of the City of Cincinnati.

Circa 1951 schematic drawing of Cincinnatis Central Parkway Subway. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

PREFACE

Anomalous in the history of public transportation in the United States is Cincinnatis Rapid Transit Loop and its two-mile, never-used subway. The 1920s-era tunnel, the most significant surviving vestige of an ambitious countywide transit plan, is also a monument to the era when American cities were masters of their own fate. The Rapid Transit Loop was conceived and funded locally to reconcile a local problem; it was killed by top-down federal policy that ensured the private automobile would reign supreme in all American cities.

To understand why the subway is vilified to this day, it is appropriate to begin with a hit piece from the era in which the project was killed:

Not only was it built extravagantly, but the part already built is inefficient and inadequately designed. It is designed for a different gauge than our streetcar system. Even if the gauge is changed, surface cars are too light to operate at high speed in the tunnel, and subway trains are too heavy to operate on surface rails in our streets. In other words the whole thing is a botch, which is falling into disrepair.

The above passage, excerpted from Rapid Transit Tunnel Is Called Botch, an article that appeared in the October 28, 1929 Cincinnati Post, is emblematic of the central problem that has afflicted the subway, and public transportation generally, in Cincinnati for nearly one hundred years. Every detail of the passage is at least misleading, if not entirely false. Yet it, like dozens of similar articles, was printed shamelessly and unanswered in a major daily paper.

The first shovelful of dirt is lifted from the canal on January 28, 1920. Courtesy of City of Cincinnati.

In short, the problem with Cincinnatis subway has never been its initial plan or the tunnel itselfits been communication. Due to a lack of attention by scholars or investigative journalists, the subways history has been told by the victorsthe forces that killed the project in the late 1920s and those who have succeeded in defeating later efforts to improve the regions public transportation by invoking subway myths. As a result of these deceptions, nearly everything most Cincinnatians today know about the subway is factually and interpretively inaccurate.

The biggest misconception surrounding the subway is that its story is over. This book is merely a snapshot of the subways first century, and by chance its writing coincided with the Rapid Transit Tubes Joint Reconstruction Project. Repairs undertaken in Spring 2010the most significant since the tunnel was built in the early 1920sensure that the tunnel will remain usable for its intended purpose for generations to come. With any luck, that day will arrive in the upcoming decade, and in 2020 Cincinnatians might mark the subways 100th birthday with a festival on Central Parkwayand then ride it home.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank the following people who aided in researching and editing this book: John Luginbill, Rob Saley, John Schneider and the Ohio Book Store; and the librarians at the Hamilton County Law Library, the Cincinnati Historical Society Library, the Cincinnati-Hamilton County Public Library and especially Suzanne Maggard at the University of Cincinnati Archives and Rare Books Library, who directed me to much of the information and visuals contained herein that are new to the public. I also wish to thank Brad Thomas and my father, Dan Mecklenborg, for their legal advice.

I wish to thank the following people who donated photos, granted access to rooftops or who directly assisted me while taking these photographs: John Luginbill, William Cavaness, Noel Prowles, Nick Sweeney, Andy Holzhauser, Ronny Solerno, Nick Guerry, John Schneider and helicopter pilot Dan Kelly.

INTRODUCTION

Any discussion of Cincinnatis failed subway project must begin with a brief recount of the citys local characteristics and nineteenth-century development, which necessarily begin with a description of the contour of the Ohio Rivers northern bank. Whereas other river towns occasionally became part of the river, the upper alluvial plaina geologic oddity stretching between todays Fourth Street and the base of Mount Auburngave Cincinnati a decisive advantage over similarly inauspicious frontier settlements along the Ohio. This natural rise motivated construction of Fort Washington; protection from both floods and natives made Cincinnati Americas first western boom town.

But by 1850, when Cincinnati nearly surpassed both Boston and Philadelphia in population, its industry and poor residents sprawled onto the lower alluvial plain, the larger areas of flat land that surround the upper flood plain on three sides. With the city boxed in by hills and having almost no available flood-proof sites available for industry, after the Civil War investors shifted their attention to fledgling St. Louis and Chicago. European immigrants followed, ending Cincinnatis fifty-year run as Americas leading inland city.

Expanses of flat and flood-proof land five miles north of Cincinnati were made accessible by the appearance of electric streetcars in the late 1880s, but long streetcar rides tested the patience of riders and were inherently unprofitable; the Cincinnati Street Railway was limited by law to charge five cents per passenger, no matter how long the route. But in 1912, a plan appeared that promised to solve all of these problems: A sixteen-mile rapid transit beltway utilizing the citys obsolete canal, unpopulated hillsides and ravines would enable large-scale development of the interior of Hamilton County and give the city of Cincinnati leverage in its efforts to annex new industrial and residential areas. In addition, the beltway would provide entry to the old city for the countys nine interurban railroads, which, since their inceptions, had been relegated to ignominious and unprofitable terminals on the citys periphery.