The jungle has swallowed them.

A S IF ANNOUNCING NOTHING MORE MOMENTOUS than a patch of turbulence, Tommy Janis calmly confirmed the worst. The three-blade prop had spun to a halt. The cataclysmic scenario, the one Janis and the other three American military contractors aboard the aircraft had shrugged off for so long, was now unfolding over Colombias imposing Andes Mountains. Their single-engine Cessna 208 Grand Caravan, packed to the gunnels with radios, high-tech cameras, and automatic rifles, was going down.

All the crew members could do was buckle their shoulder harnesses and put their faith in Janis, a first-class flyboy with an uncanny knack for survival. A thirty-two-year army veteran who served in the Vietnam War and was awarded a Bronze Star, Janis viewed his job as another way to be a soldier, another way to make a difference. He had earned his stripes in Colombiaand the moniker ace of the basetwo years earlier when the engine of his Cessna surveillance plane quit over the Caribbean Sea. He simply pointed the plane toward the coastal city of Santa Marta, twenty-five miles away, and began gliding.

Tommy made it look easy, said Douglas Cockes, a former U.S. Customs Service pilot and private contractor who worked with Janis in Colombia. If an engine quits right next to an airport, probably half of all pilots would still miss the runway. But Tommy was able to get in there from twenty-some miles out. He made a perfect landing, rolled to the end of the taxiway, then jumped out and lit a cigar.

This time, Janis had two options. He could try to keep the Cessna aloft long enough to clear the mountain ridge and reach their original destination, a nearby Colombian military base. Or if that didnt work, he would have to put her down somewhere in the wilds of southern Caquet state.

And that would not be good.

Like much of Colombias Deep South, Caquet was enemy territory. Home to cattle ranches, cowboys, and twisting, muddy rivers that drain into the Amazon, the region was better known for all the things that ail Colombia. Glossy green coca bushes, the raw material for cocaine, dotted the flatter parts of the landscape. The Colombian government didnt have enough troops in Caquet to provide much security, which made it possible for Marxist rebels to extort businessmen, kidnap farmers, and manage the local drug trade. But if the rebels kingdom was vast, their subjects were few. Only a handful of Colombians set foot in these parts and for good reason: Caquet was Colombias Sunni Triangle.

The Americans aboard the Cessna were there to help change this dynamic. Though not active-duty military, they were, in effect, the tip of the U.S. spear in the long-running war on South American drugs. They worked for California Microwave Systems, a little-known subsidiary of Northrop Grumman, the Maryland-based aerospace giant which was a major client of the U.S. Defense Department. In the days before the Pentagon began contracting out some of its military and intelligence chores, their work might have been handled by the CIA.

Their missions were classified. As high-tech eyes in the sky, the Americans were supposed to find and photograph cocaine laboratories. The guerrillas were deeply involved in the cocaine trade, thus the data collected aboard the Cessna could also be used for counterinsurgency operations. The contractors were always on the lookout for clandestine airstrips and makeshift river ports used to evacuate bricks of cocaine. From the air, the crew could also spot fifty-five-gallon drums, chemical stains on the jungle floor, and maceration pits where coca leaves were mixed with uric acid and other toxic ingredients to make the white powder. They also had forward-looking infrared. Known as a FLIR, the pod that protruded from one side of the plane could identify heat given off by people, engines, even the microwave ovens drug makers used to dry cocaine. Whenever antidrug agents found a microwave oven deep in the Colombian rain forest, they could be pretty sure the cook wasnt zapping popcorn.

The Americans recorded what they saw on video and digital cameras and fed the data to the fortresslike U.S. embassy in Bogot. The information was then relayed to Colombian ground forces that would move in to torch the labs and track the rebels. Then, the whole chain of events started again, with peasant farmers planting more coca, Jungle alchemists building more labs, and gung ho drug warriors launching more raids. This self-perpetuating game had been going on for years due, in part, to the overwhelming U.S. focus on cutting off the narcotics supply at its source rather than reducing demand and treating drug addicts at home.

Now Washington was wading deeper into the Colombian war.

These surveillance missions were part of a multibillion-dollar program, known as Plan Colombia, that had made the Andean nation the largest recipient of U.S. foreign aid outside the Middle East and Afghanistan. Much of the $700 million in annual assistance was funneled into programs to eradicate coca fields, blow up cocaine factories, and intercept drug-laden aircraft. Unfortunately, the effort had failed to roll back narco-acreage in any substantial way or to curb the flow of cocaine into the United States. Attacking illegal drugs was like plowing the sea. But Plan Colombia did produce in the early days hundreds of high-risk, high-paying jobs for American contractors.

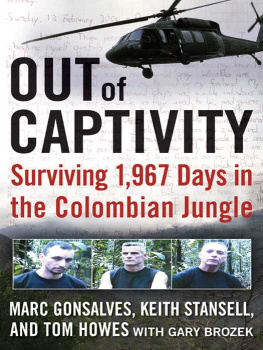

T HE MEN IN THE C ESSNA THAT sunny Thursday morning, February 13, 2003, believed they were fighting the good fight. But truth be told, they were mostly in it for the money. Next to Janis in the right seat was copilot Thomas Howes. A quiet, gray-haired Yankee from Cape Cod, Howes nonetheless wielded a sly sense of humor. One of his colleagues compared him to a master doctor who could give you the needle so expertly that you wouldnt know youd been jabbed. After a stint flying DC-9 commuter jets out of New Yorks La Guardia Airport, Tom had gravitated south where hed gotten hooked on the warm weather, good food, and pretty girls of Latin America. At one point while hanging out in Lima, Peru, Howes missed seven consecutive flights back to the United States. It was such a change of pace and flavor, Howes said. I was mesmerized. And I lost that drive to move up the aviation ladder back in the States.

Over the years, Howes had logged thirteen thousand hours flying for private contractors in Guatemala, Haiti, Peru, and Colombia. Along the way he married a Peruvian woman and together they had a boy named Tommy. Howes was thrilled to be earning upwards of $150,000 with California Microwave on a schedule that took him to Colombia for four weeks at a time, with two weeks off back home. Howes sometimes told his friends: I want to keep these paychecks coming until Im too old and feeble to read them.

In the back of the plane operating the cameras and the FLIR was Marc Gonsalves. A thirty-year-old native of Bristol, Connecticut, who often wore a goatee, Gonsalves was an eight-year veteran of the air force who worked as an intelligence analyst. As a young NCO, he had married an exotic dancer named Shane whom hed met at a bar near MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa. The couple had three kids they were raising in the Florida Keys. Though Marc loved his job, the promotion cycle was slow and he was earning only about $28,000 a year. The prospect of putting his kids through college worried him. Thus, when California Microwave offered him a job and a gigantic raise, he eagerly made the switch to the private sector.

Alongside Marc in the back was Keith Stansell, a six-foot-two-inch former marine, avionics whiz, outdoorsman, and self-described southern redneck. Keith had used his fat salary to climb out of debt and was now enjoying life in his free time by fishing in the Gulf of Mexico or disappearing into the Montana outback to hunt deer. Still, he sometimes mused about quitting so he could spend more time with his fiance and their two young children in rural Georgia. His master plan was to open a crop-dusting business, then kick back on the weekends with his family, his dog, Buck, and a tall glass of Jack Daniels and Coke. Or was it? Keith, it seems, had built up an exotic, if complicated, parallel life in Colombia. He was dating a Colombian flight attendant and shortly before Thursdays mission hed found out that she was pregnantwith their twins.