NATHAN M. GREENFIELD

THE BATTLE OF

THE ST. LAWRENCE

THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN CANADA

This book is dedicated to my children, Pascale, whose excitement when I turned up something or someone new almost equalled my own, and Nicolas, who asked all the right questions when we toured the naval base in Halifax, and to Micheline, who walked with me as I travelled through the undiscovered country of the past.

No Allied seaman could ever stomach the arrogant posturing of the U-boat men that we watched in movie newsreels: the brass bands, the vainglorious songs, the strutting admirals, the buxom maidens draping garlands of flowers about the necks of their returning warriors. Only a Nazi could transform the sinking of helpless merchant ships and the drowning of unarmed sailors into Wagnerian heroics. Certainly we had no such illusions, and when one U-boat survivor attempted an arrogant, arm-in-the-air Nazi salute upon being hauled aboard a Canadian corvette, he was unceremoniously bundled back over the side to rethink the situation.

JAMES LAMB

CONTENTS

T he subtitle of this bookThe Second World War in Canadawill, no doubt, surprise many.

Wasnt the Second World War over there? In the skies over England? At Dieppe? Across North Africa, Italy, Normandy, Belgium and Holland and in Germany? Werent its greatest battles on the Russian steppes and across the Pacific? Canadians fell at Juno Beach, in Ortona, along the canals of Holland, in Hong Kong, and thousands died on the North Atlantic.Over there? Yessurely not in Canada.

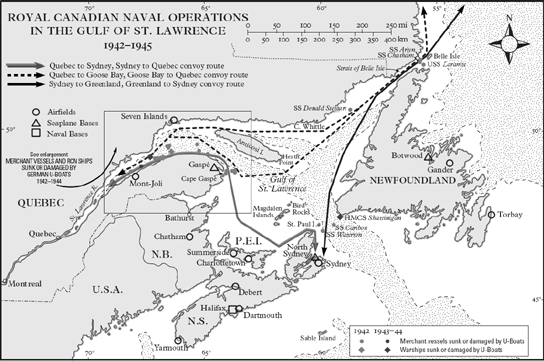

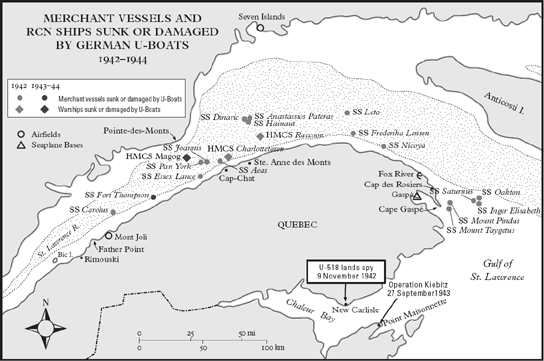

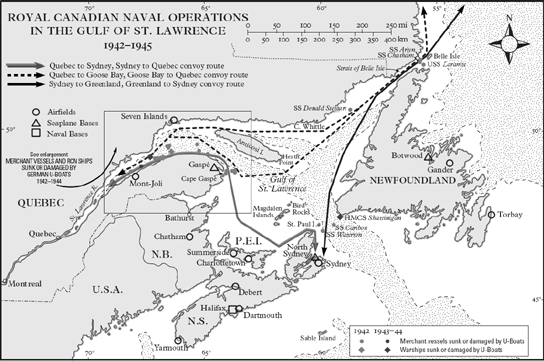

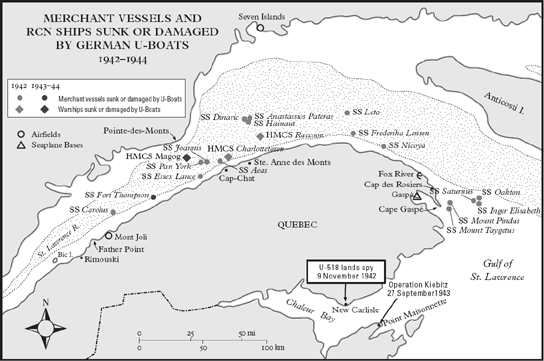

But between 1942 and 1944, more than 28 ships were torpedoed, 24 of these sunk, and more than 270 Canadians and scores of others did diein Canada. They died in the Battle of the St. Lawrence, the only Second World War campaign fought inside North America.

Many died within sight of land or of the lights that shone from the small towns and villages strung out along the rugged coast of the north shore of the St. Lawrence and Quebecs Gasp Peninsula. One hundred and forty-five were officers and ratings aboard HMCS Raccoon, Charlottetown, Magog and Shawinigan, four of the dozens of Royal Canadian Navy warships that, after the torpedoing of SS Nicoya and Leto on the night of May , 1942, were tasked with escorting convoys in Canadas largest river and the gulf. One hundred and thirty-seven men, women and childrenincluding forty-nine civilians (of whom eleven were under ten years old), forty-nine Canadian and British servicemen, eight American servicemen and thirty-one crew members, most of whom were from Port aux Basquesdied when a torpedo fired from U-69 mortally wounded the Newfoundland-Nova Scotia ferry SS Caribou at 2 a.m. on October 14, 1942. Another hundred menFinns, Belgians, Dutchmen, Greeks, Englishmen and American GIs and sailorsdied, victims too of the torpedoes fired by the fifteen German U-boats that between 1942 and 1944 invaded Canadas home waters; one ship, SS Carolus, was torpedoed 10 kilometres downriver from Rimouski, Quebec, fully 600 kilometres from the Atlantic and some 250 kilometres from Quebec City.

Like all battles, myths have accreted to the Battle of the St. Lawrence. One holds that the government staged the sinkings to help sell Victory Bonds. Another, which surfaces from time to time on uboat.net, is that U-boats landed to buy groceries. Still another tells of German officers stopping for a beer and to listen to music at an htel. By far, however, the most persistent myth is that wartime censorship prevented word of the battle from reaching beyond the Gasp.

The claim appears to have a good pedigree, stretching back to the hours after SS Nicoyas sinking on the night of May 11, 1942. The news release that confirmed the sinking declared that any possible further sinkings in this area will not be made public in order that information valuable to the enemy may be withheld from him. At first, the policy seemed to have teeth, at least in the House of Commons, where on May 13 the Speaker ruled against Gasp MP Sasseville Roys attempt to pry more information from Prime Minister Mackenzie Kings government. The cutline on Jack McNaughts October 15, 1949, Macleans magazine article, The Battle of the St. Lawrence, is A story thats never been told. Twenty-three years later, Peter Moons The Second World War Battle We Lost at Home, published in Canadian Magazine, was subtitled The War Story Our Leaders Kept Quiet. James Essex subtitled his 1984 memoir, Victory in the St. Lawrence, Canadas Unknown War. The claim was repeated in 1995 in Brian and Terence McKennas NFB film U-boats in the St. Lawrence.

The famed fog of war conceals much, but in this case it hardly hid much about the Battle of the St. Lawrence from Canadas kitchen tables and radios.stories, but they clearly told Canadians that ships had been sunk in the St. Lawrence. Three days later, the Ottawa Evening Citizen reported that the sinkings had caused the war risk premium for ships using the St. Lawrence to double from 1.5 to 3 per cent.

On July IO , Roy asked in the House if the minister is disposed to make a statement about the torpedoing of three more ships last Sunday night. According to LAction Catholique, half the people in Quebec City knew of the sinkings before Roy asked the question. The sinkings of USS Laramie and SS Chatham, Arlyn and Donald Stewart in late August and early September 1942 did not make the newspapers. The sinkings of HMCS Raccoon and SS Aeas on September 6 and SS Oakton, Mount Taygetus and Mount Pindus on September 7 did. A week later, headlines told of the loss of HMCS Charlottetown. Canadians read that the torpedo tore into the engine room, trapping the men on watch before they could reach the upper deck. Clouds of black smoke rolled along the decks. Before they could launch the lifeboats the vessel went down by the stern, just as the survivors jumped clear and into the frigid water. They read of their sailors being killed within sight of land when their own depth charges exploded.

On September 13, the Ottawa Evening Journal told of the daring midday attack that had sunk SS Frederika Lensen the previous July. Two days later, the Journals headline read U-BOAT SINKS SHIP BELOW RIMOUSKI. LAction Catholique asked, Ce qui se passe en Gaspsie? (What is going on in Gasp?). The stories that followed the sinking of Caribou on October 14 spared readers little: Bodies were found floating a short distance from where the ship was attacked, and a number of caskets are being forwarded by train to Port aux Basques.

In early November 1942, Naval Minister Angus Macdonald spoke out against the rumour that U-boat crews were coming ashore to buy supplies; he gave the number of ships sunk in the whole river and gulf area as twenty. The Halifax Herald overstated things by saying, R.C.A.F. Gets Another U-boat, but, nevertheless, gave Canadians more than a few details about the air war being conducted against the Nazi invaders.

In March 1943, newspapers reported Quebec legislators Onsime Gagnons and Roys charges that the problems in the navys command structure had prevented it from reacting to save a convoy that was attacked the previous September 15 and that as many as forty ships had been sunk in 1942. On March 17, 1943, papers reported Macdonalds speech, which not only defended the navy but also included the names of every ship sunk in 1942. After a tour of the Gasps naval and army bases,

Next page