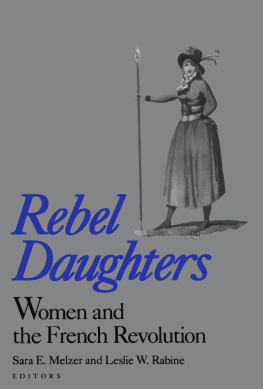

The women have certainly had a considerable share in the French revolution: for, whatever the imperious lords of the creation may fancy, the most important events which take place in this world depend a little on our influence; and we often act in human affairs like those secret springs in mechanism, by which, though invisible, great movements are regulated.

H ELEN M ARIA W ILLIAMS

T HE N ATIONAL A SSEMBLY Frances first constitutional governmentmet between October 1789 and September 1792 in the covered riding-school of the Tuileries palace in Paris. The long, narrow mange [see Words and Phrases] had been remodelled to accommodate the deputies with a classical austerity intended to correspond to the gravity of their new political responsibilities.

Although women did not possess the rights either of voting or of holding office, they were permitted into the halls galleries to observe and marvel at the workings of the administration and the debates on Frances future. On any given day in the spring of 1791, four women might have been sitting among the onlookers gathered to watch the Assemblys proceedings.

The first was a dark-haired, red-faced woman of twenty-five, looking perennially dishevelled despite her expensive, extravagantly d-collet dress. As she watched the men below her debate, it was clear that several of them were her friends and that she was well acquainted with every argument they put forth. She leaned eagerly forward to catch every word, fiddling distractedly with a twisted scrap of paper that showed off her fine hands.

This was Germaine de Stal, one of the richest women in Europe, daughter of Louis XVIs former Finance Minister Jacques Necker [see Secondary Figures], whose dazzling intelligence never quite consoled her for not being beautiful. She was at the heart of a group of progressive aristocrats she believed would shape a new, reformed France ruled by a constitutional monarchy; her centrist coterie included the hero of the American War of Independence, the marquis de Lafayette, toeing an uneasy line between his liberal principles and his loyalty to the king.

Her critics found her over-bearing and even her friends called her self-centred, but such was the power of Germaines intellect and conversation that within half an hour of meeting her most people, despite themselves, were utterly captivated. I know of no woman, nor indeed any man, more convinced of his or her own personal superiority over every other person, wrote one of her lovers, Benjamin Constant, or who allows this conviction to weigh less heavily on others.

Stal, as a novelist, social commentator and literary theorist, left behind a wealth of source material that, unusually, spans the entire period before, during and after the revolution. She is not only the best and most consistently documented of this books six women, in terms of her own letters and of being mentioned in other peoples correspondence and memoirs, but also the one who wrote the most eloquently about the revolution itself.

Germaine had little time for other women, but one acquaintance who might have been sitting nearby was the delectable Thrsia de Fontenay. Just eighteen years old, already married for four years and the mother of a little boy, tender-hearted Thrsia was the toast of Parisian society; the only thing she enjoyed more than pleasure was attention. She would have been wearing fashionably simple, patriotic clothesa white muslin dress with a tricolour sash fastened with a brooch made out of one of the shards of the fallen Bastille. At her side was her radical lover whose brother, a former marquis, was closely allied to the most extreme-left deputies including Maximilien Robespierre.

Manon Roland, the thirty-seven-year-old wife of a provincial civil servant, sat in another part of the gallery, well away from the world of high society. Demurely dressed, eyes downcast, her virtuous exterior concealed an ardent, rebellious heart. Drawn to Paris in 1791 by the events taking place there, she and her husband became central members of a group of middle-class republican lawyers and journalists who included Robespierre and the progressive journalist Jacques-Pierre Brissot. Unlike Thrsia de Fontenay, Manon had chafed at the old order of things. When the revolution came it was the fulfilment of all her dreams.

Manon watched the debates as keenly as Germaine, knowing the deputies speaking, and their arguments, because many of them met regularly in her drawing-room. But while Germaine would have given her guests champagne; Manon proudly served sugar-water. With her love of order, she deplored the chaos of the Assemblys sessions: the uncontrollable deputies shouted over one another to make their voices heard, preventing the business of the day from being accomplished.

Pauline Lon had no such scruples. She heckled from the galleries, shouting down moderates like Lafayette and cheering her hero Robespierre. No portrait of her survives if one was ever made but as a thirty-three-year-old single woman of the streets, who helped her widowed mother run the family chocolate-making business and look after her five younger brothers and sisters, it is likely that she was well made and strongly built. A fresh white handkerchief covered her hair, pinned up with a tricolour rosette, and she was wearing a blue woollen waistcoat over a white chemise, the sleeves pulled up to expose her tanned forearms; a red and white striped skirt with an apron; and wooden clogs.

Sixty-five per cent of French women of the late eighteenth century could not write their names; the illiterate would have been slightly fewer in Paris. Pauline Lon could read and write she had been educated by her father but she was a woman of the people and, as with most of them, it is harder to build up a rounded picture of her life because the sources concerning her are so scarce. No onlookers described her behaviour as a child; she left no diaries or letters. In a rare document produced while she was in prison in 1794, Lon testified to roaming Paris from 1789 onwards, frequenting political assemblies, demonstrating on the streets as well as manifesting my love for the fatherland. She was less forthcoming about harassing and beating up passers-by for not being good patriotsa synonym for devotion to the revolution.

A notable absence from the galleries on this imaginary afternoon was the former courtesan Throigne de Mricourt, who before leaving Paris in the late summer of 1790 had been such a regular observer of the Assemblys sessions that she had her own seat reserved for her. She was known for always wearing a riding-habit of an austerely masculine cut, either in red, black or white. Although she had intended her trademark costume to compel men to treat her as an equal rather than as a woman, by wearing it she became one of the feminine icons of the revolution.

Abandoned by a faithless lover and reviled for having lost her reputation, Throigne was very much alone in the world. She had suffered more at the hands of men than any of the other women here, and she was the most passionate and lonely campaigner for the liberties which the revolution seemed to promise women but ultimately failed to deliver. For nineteenth-century historians the image of pretty Throigne in her red riding-habit, her bloody sword held aloft, represented all the savage excesses of the popular revolution; but this portrait of her bore very little relation to the earnest young woman whose early hopes were so disappointed by that revolution.

Another figure completes the sextet described in this book, but in the spring of 1791 Juliette Bernard, the future Madame Rcamier, was still a bourgeois schoolgirl of thirteen, absorbed in studying English, Italian, dancing and the harp.