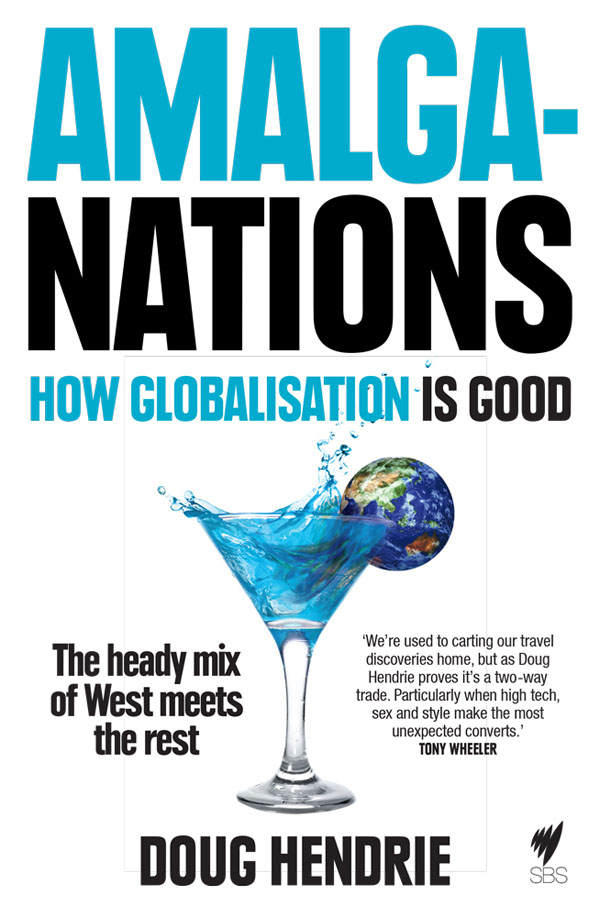

Published in 2014 by Hardie Grant Books

Hardie Grant Books (Australia)

Ground Floor, Building 1

658 Church Street

Richmond, Victoria 3121

www.hardiegrant.com.au

Hardie Grant Books (UK)

Dudley House, North Suite

3435 Southampton Street

London WC2E 7HF

www.hardiegrant.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Copyright Doug Hendrie 2014

Sections of this book have previously been published in The Diplomat, PC Powerplay and Edge magazines.

Cataloguing-in-publications data is available from the National Library of Australia AmalgaNations: How globalisation is good

eISBN: 9781743581766

Cover and text design by Josh Durham/Design by Committee

For Jess

Skipping borders: Cultures on the move

ONE SATURDAY MORNING, I sat at an Ethiopian cafe in Footscray, sipping honeyed coffee. I watched seven-foot-tall South Sudanese men, huge grins atop beanpole bodies, deftly picking their way past their five-foot-five Vietnamese neighbours. And I wondered: when, in all of recorded history, would these two peoples have previously come into prolonged contact? Most likely never. What an extraordinary thing it is, I thought, to be mobile on this modern scale, to dislodge yourself from your ancestral home driven by war, poverty or possibility.

Footscray, a gritty inner-western suburb of Melbourne, has become home to each major wave of migrants to Australia since my country began its European incarnation as an improbable prison colony. Footscray hosted poor Irish factory- and dockworkers in the 19th century, Greeks and Italians post-WWII as white Australia liberalised its white-only entry policies in a bid for scarce labour, and then, as the 20th century rolled on, came the Vietnamese and Cambodians, fleeing war in South-East Asia. In the 1990s, they were joined by economic migrants from China, refugees from the former Yugoslavia, and then, most recently, by Ethiopians, South Sudanese, Somalis and Eritreans, fleeing war or hunger or the collapse of their state. International students by their thousands have settled here, too, coming from South-East Asia, from Singapore, China and India, taking advantage of cheap rent. Now, Footscray is among the most multicultural suburbs in Australia; almost half of its residents speak a language other than English at home. But at school, the children of migrants speak English, and so become hybrid people of two places, of their parents home and theirs. This process has fascinated me for years how the children of migrants become locals, and how locals, in turn, sponge up new cultures, little by little. It happened to me. My own grandparents Scots, English, Dutch all fled British Malaya when the Japanese came in WWII, and ended up in Australia.

Ive long felt this form of globalisation the mixing of cultures previously held apart by geography, history, or hostility is improving the world, little by little.

What led to this book was a chance encounter. Footscray was buzzing, blooming, with hairdressers specialising in African braiding, pho noodle shops thronging the main drag and stores selling the trademark baggy bling clothing of hip-hop, the latest African-American musical form to go global, following jazz, blues and rock. I finished my coffee and, on a whim, entered a hip-hop store named Emete JD, all high ceilings, branded puffy jackets and faux gold chains. The Ethiopian owner, JD, approached. Could he help me?

I told him I was curious. How did his shop come to be? And why was it that hip-hop was becoming popular amongst African-Australians?

JD looked surprised. But then he smiled and told me his story.

When he first arrived in Footscray with his parents in 1996, there were a grand total of six other Africans in the area and he soon knew them all. The community was too small. How could JD make himself a new identity? What other models were there? The obvious option was hip-hop, African-American urban life turned into a full-blown culture music, dress, dance, art, all drawn from the stifling ghettos of New Yorks Bronx in the 70s. What better way for an African newly conscious of his difference to adapt to a white-majority country?

Hip-hop was a black thing. You couldnt buy the clothes here, youd have to buy them from overseas, JD said. The police used to stop us on every corner because of our baggy jeans. But it was just how we dressed.

In high school, the white boys were scared of the African kids. The small group of second-generation Africans stuck together. They cultivated their hip-hop look and a devil-may-care attitude to keep them safe. Back then whites didnt hang with Africans, JD said.

The book learning and racial politics of school werent for him. He left and began working. At a meat-processing plant, he deboned chickens and carved up sides of beef, working long hours. Hip-hop had given him an identity, but it had also given him an idea. The culture was taking off everywhere, from Africa to Australia, but buying gear was hard. In 2007, he had enough money to open Emete JD.

You know, when I came here, I couldnt find home, he said. So I created it.

When he finished his story, JD cocked his head and said, Come with me, meet my friend, an African rapper. And I went along, feeling deliciously out of place in a city I thought I knew well. His friend, who performs under the name African Third Life, sat at a cafe table, rhyming quietly to the music in his head. Why, I asked him, had hip-hop become big for African migrants? He told me this:

Hip-hop is much bigger in Africa than it is in the USA. Music in Africa is for breakfast, lunch, dinner. The blues came from Africans in slavery [in the US], rap from Jamaica, and they were African slaves too.

Later, I looked it up. He was right. Across swathes of black Africa, hip-hop is king. How extraordinary: a musical form that began with the rhymes of West African bards, that travelled on slave boats to the Americas and there, in plantations, was kept alive; music that, after centuries, would eventually become part of dancehall culture in Jamaica and then erupt into hip-hop in New York City, and from there, leap back to Africa to become street music, proud music, protest music, slumland and clubland music. And now, a new iteration: African-Australian rap, joining the white Aussie skip-hop scene. There are dozens of artists in Melbourne alone, I found, artists such as South Sudaneseborn rapper Mxc Wol; Namibian-Australian 1/6; ex-street kid Macc Too, a young Rwandan woman; and the mainstream duo Diafrix, who hail from Eritrea and the Comoros Islands artists who make songs with powerful messages, a stark contrast to the dominant American strain of gangsta rap. My encounters left me energised and surprised. If these mixtures, these borrowings, these adaptations were happening in the small part of the world I see on a daily basis, what might be happening elsewhere?

Im curious by nature fascinated by how people live their lives, by how people make their own meaning. Why not go and see for myself how the world was changing? It could be that Id sense a bland sameness: airports, hotels, malls, Hollywood blockbusters, generic pop, jeans, aspiration to wealth and Westernness. But it could be something else, like the African-Australian hip-hop scene Id found.