Many people provided different types of assistance in the preparation of this book. In the first instance, the Tezcatlipoca Symposium that provided the basis of the present publication, I thank the Mexican Embassy in the United Kingdom, especially Ambassador Juan Jos Bremer and Minister Ignacio Durn, who helped in various ways. I thank the present Mexican Ambassador to the United Kingdom Diego Gmez Pickering, Deputy Head of Mission Alejandro Estivill, and Education Attach Evelyn Vera. My sincere thanks to Chris Winter, who helped with the Tezcatlipoca Symposium, making my life easier. I also thank Alison Taylor-Smith for the design of the poster. I owe special thanks to Brooke Mealey, who read the entire manuscript. Her great attention to detail made the volume appear flawless. Last but by no means least, I thank the staff of the University Press of Colorado, particularly Darrin Pratt and especially Jessica dArbonne, who provided help at every stage of publication. Her assistance has been invaluable.

Introduction

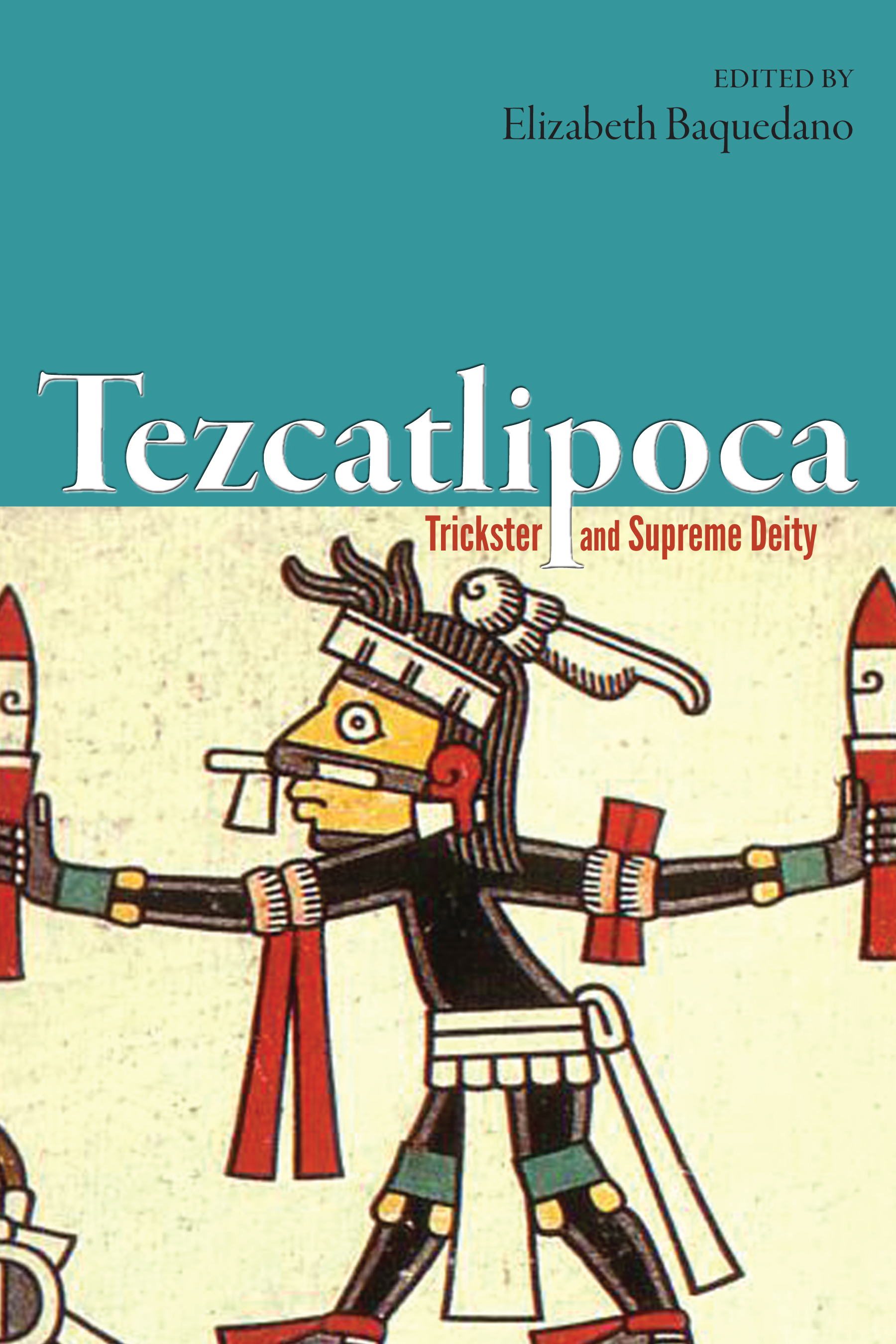

Symbolizing Tezcatlipoca

NICHOLAS J. SAUNDERS AND ELIZABETH BAQUEDANO

DOI: 10.5876/9781607322887.c000

A presence of absence defines the ambivalent nature of Tezcatlipoca, the supreme deity of the Late Postclassic Aztec pantheon. In the dark ephemeral reflection of his obsidian mirror and the transient sound of his ceramic flower pipes lies the sensuous nature of a god who mediates materiality and invisibility with omniscience and omnipresence. These qualities are evident not only for the Aztecs but also for scholars today. As Michael Smith (this volume) points out, only recently have we begun to move beyond the written words and painted images of the codices to assess a different kind of Tezcatlipocas material tracesthe objects in which the numinous becomes tangible.

In one sense, Tezcatlipoca was a reification of age-old Mesoamerican patterns of symbolic thought, which abstracted supernatural connotations from the natural world. Specifically, Tezcatlipoca emerged as a supernatural embodiment of cultural attributes inspired by, and bestowed upon, aspects of regional geography/geology and local fauna by the Late Postclassic, pre-Aztec cultures of the Valley of Mexico that were shaped by analogical symbolic reasoning and political exigencies (see Umberger, this volume). Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the deitys relationship with obsidian (itztli) and the jaguar (ocelotl)two natural kinds imbued with ideational significance across Mesoamerica, recombined in metaphysics, and given physical expression in a distinctive kind of material culture: obsidian mirrors (Smith, this volume).

These reflective devices were powerfully ambiguous, not least because they shone with a dark light. They partook of what has been called a pan-Amerindian aesthetic of brilliance, ). Baquedanos (this volume) analysis of Tezcatlipocas golden ornamentation, where brilliance and the sounds of bells (symbolic of warfare) reinforce this conceptual association, is epitomized by Durns description.

Tezcatlipoca was thus a product of both a conceptual landscape that drew upon the physical environment (and what was made of it metaphorically) and a cultural landscape composed of the ever-changing political milieu in which he operated, from the Late Postclassic to the Early Colonial period (, 22527).

Hitherto, with the exception of Guilhem ). Our focus is on the relationships among landscape, deity, and constructions of worldview as mediated by objects and their role in ideological enforcement.

A God in the Landscape

Obsidian mirrors, like Tezcatlipoca himself, are ambiguous (see Klein, this volume). Their raw material is mined from the earth and shaped by people, and, if we believe ethnohistorical sources, they appear to give their owner access to the intangible world of reflections, where souls, spirits, and the immanent forces of the cosmos dwell. From this perspective, it is hardly surprising, though in no way predictable, that Tezcatlipoca is a potent combination of such power imagery whose name is a linguistic apotheosis of Aztec conceptual thoughtthe Lord of the Smoking Mirror (, 412).

Tezcatlipocas omnipresence was commented upon by Sahagn (, book III: 11).

, 44) point that the technology of enchantment is founded on the enchantment of technology (original emphasis).

The associations between Tezcatlipoca and obsidian (in its various cultural forms) were extended into the realm of animal symbolism as represented by the gods relationship with the jaguar (Panthera onca [ocelotl]). Across Mesoamerica and South America, the jaguar was the salient predator of the natural world, a prototype for cultural categories of agonistic activities such as hunting, warfare, and sacrifice and as the spirit familiar par excellence of shamans, priests, and political leaders (, book XI: 1).

A dramatic example of Tezcatlipocas feline associations is his transformational manifestation as the jaguar Tepeyollotl (, 334) identifies the individual engaging in auto-sacrificial bloodletting as Tezcatlipoca, in his guise as Tepeyollotl, because of his spotted-feline apparel.

The identification of Tezcatlipoca with the feline is enshrined in Aztec mythology, where he is described as a nocturnal deity whose alter ego was the jaguar (, book XI: 3).