ForAnn

Contents

1, 14851527

2, 152730

3, 153032

4, 153033

5, 153335

6, 1535

7, 153336

8, 1536

9, 1536

10, 153637

11, 153639

12, 153639

13, 153639

14, 153839

15, 153839

16, JanuaryJune 1540

17, JuneJuly 1540

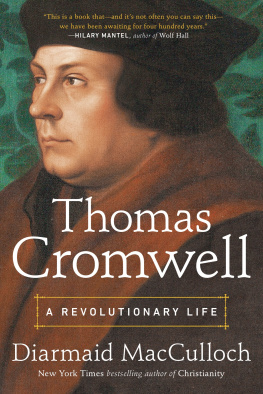

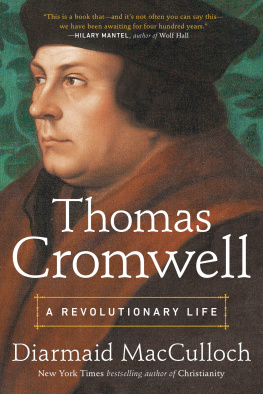

This book sets out to tell the story of the man who, apart from King Henry himself, was the dominant personality in one of the most eventful eras in English history: Thomas Cromwell, the kings chief minister and principal reformer of the church.

In preparing the work I have freely used the definitive studies of the late Professor Elton and other recognized scholars. Most of the evidence, however, is derived from primary sources.

The amount of such material available on Cromwell is huge, including nearly twenty substantial volumes of LettersandPapers in which Cromwells name appears on almost every page. For seven or eight years, there was hardly an issue of any significance in which he was not involved. To keep this book down to manageable size, a number of subjects will be covered as concisely as possible. These include Henrys first divorce negotiations, the theological issues of the Reformation and the constitutional legislation of the 1530s, all of which are elements of Tudor economic and social history. Notes will make reference to works in which these important subjects have been treated more than adequately by other writers.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Thomas Cromwell left no personal works or memoirs, and the official papers, despite their bulk, do not necessarily reveal much of the inner man. Occasionally in this book, therefore, I allow myself the luxury of drawing a few inferences. This is done guardedly and with suitable caveats, but I believe that it is justified in the circumstances.

As usual in works on the Tudor period, a note is needed on terminology. To avoid repetition, the words evangelical, reformer and Protestant are used interchangeably, evangelical being used in its sixteenth-century sense, meaning Gospel. Lutheran serves well enough for most of the leading English evangelicals during the 1530s, like Cromwell and Cranmer. The new learning and the Gospel are terms synonymous with Protestant faith. Catholic is not always as easy to define as it sounds. Lutherans frequently claimed that their confessions followed the Scriptural Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church rather than the medieval religion which they contested. Unless otherwise indicated, however, I use Catholic to cover all those who opposed Luther and held to the religion in which they grew up. Nothing derogatory is implied by medieval, Papist or Papalist; the latter two are most useful in distinguishing those like Thomas More from others, who, though they supported King Henrys Royal Supremacy, remained broadly Catholic on so much else.

Generally the word councillor, or occasionally servant, is preferred to statesman when discussing the policies of Cromwell and other leading men surrounding the king. By statesman we usually mean one who has some freedom to formulate and execute policy, but of Cromwells master the Milanese ambassador once said that His Majesty chooses to know and superintend everything himself. I hope readers will not mind seeing these words more than once during the narrative, for often they help to understand what is happening.

Quotations are generally given in modernized spelling, but in order to try and capture a sixteenth-century feel, the Tudor phraseology is usually retained. Foreign names are anglicized unless there is a pressing reason not to do so.

PART I

1

Well might many a famous individual from the past, were he able to read historys verdict on him, echo the cry of Shakespeares Cassio: Reputation, reputation, reputation! I have lost my reputation.

In our times despite the sterling labours of the late Professor G.R. Elton the very mention of Thomas Cromwells name is likely to conjure up a baleful spectre in the minds of many. He was, we are repeatedly informed, the chief destroyer of a vibrant, idyllic English medieval church, the man who plundered the monasteries and consigned to oblivion centuries of pious, devotional tradition, imposing in its place an alien creed of justification by faith alone; the prime instigator and enforcer of harsh Tudor treason laws; a ruthless, sinister, unsmiling Machiavellian who cynically cut down Anne Boleyn and all others who dared oppose him, before finally receiving his much deserved deserts when he overreached himself and lured King Henry into an disastrously unsuitable marriage with Anne of Cleves.

I do not remember for sure what made me first begin to wonder whether all of this might be largely fanciful, and whether the real Thomas Cromwell, if only we could meet him and become better acquainted, might take on a less fearsome and altogether more agreeable aspect. It was not a craving to be novel just for the sake of it, but what began as no more than a hunch quickly developed into a conviction. Readers will be able to decide for themselves if they care to go down the same route.

Like many substantial and controversial men in history, only patchy details about Cromwells early life are known. The main sources are Eustace Chapuys, imperial ambassador to England during much of the 1530s; Reginald, later Cardinal Pole; Matteo Bandello, the Italian writer who became bishop of Agen in France; and John Foxe, the Elizabethan historian and martryologist. Of these four Chapuys knew Cromwell best, but even he is frustratingly brief. Cromwell, says Chapuys, was the son of a poor blacksmith who lived and is buried at a small village near London. His uncle was cook to Archbishop Warham. In his youth Cromwell was somewhat ill conditioned and wild (malconditionn), and he spent some time in prison before travelling in Flanders, Rome and throughout Italy. The reason for the imprisonment is not stated.

Reginald Pole also knew Cromwell personally, though not as well as Chapuys did. Pole confirms Cromwells birth near London, but calls his father a cloth shearer. Cromwell, Pole continues, then became a private soldier in Italy before pursuing a more secure, if less adventurous, way of life as an accountant in the service of a Venetian merchant.

The Italian connection is taken up by Bandello, with his engaging story of the wealthy Florentine merchant, Francesco Frescobaldi, chancing one day to meet a poor youth (unpoverogiovane) in the streets begging alms for the love of God. Seeing him in a bad condition though gentle in appearance (malinarneseecheinvisomostravaaverdelgentile), Frescobaldi was moved to pity, especially when he learned that the youth hailed from England, a country he knew and loved. He asked him his name. My name is Thomas Cromwell, he replied, the son of a poor cloth shearer (dunpoverocimatoredipanni). He had escaped from the battle of Garigliano in Italy where he served as a page or servant to an infantryman, carrying his pike. Frescobaldi invited Master Cromwell into his house as his guest and offered him shelter, food and clothing. After a short stay he gave him money and a new horse. Thus refreshed and replenished, the grateful youth set out to return to England.

These accounts complement rather than contradict each other, though with one interesting exception. Cromwells father was a smith (Chapuys) but a cloth shearer (Pole, Bandello). Foxe clarifies the matter with the information that Cromwell was born in Putney or thereabouts, being a smiths son, whose mother married afterwards to a shearman. So the smith was Cromwells natural father and the shearman (or shearer) the step-father. Foxe gives no reason why his mother married again, but the only obvious one, unless the second marriage was illegal, is that his father, the smith, died shortly after Thomas was born. So it is not certain whether Cromwell was the name of the father or step-father.

Next page