THOMAS CROMWELL

THOMAS CROMWELL

The untold story of Henry VIIIs

most faithful servant

TRACY BORMAN

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

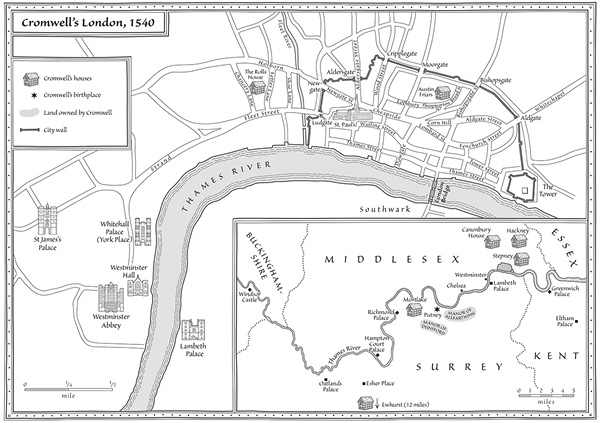

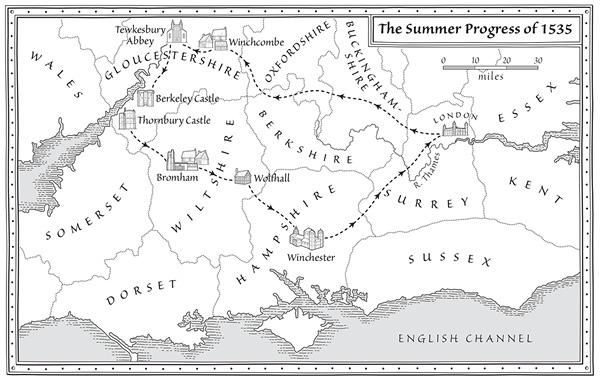

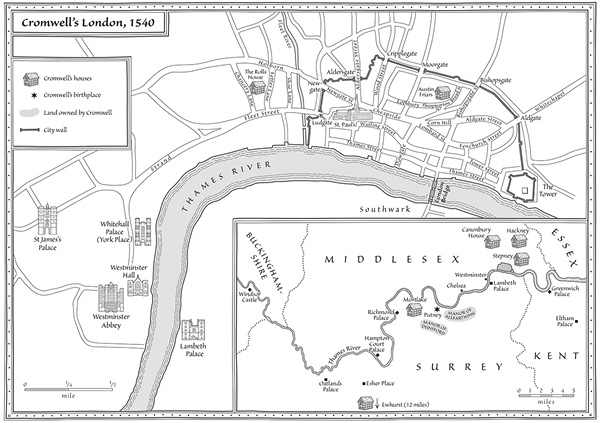

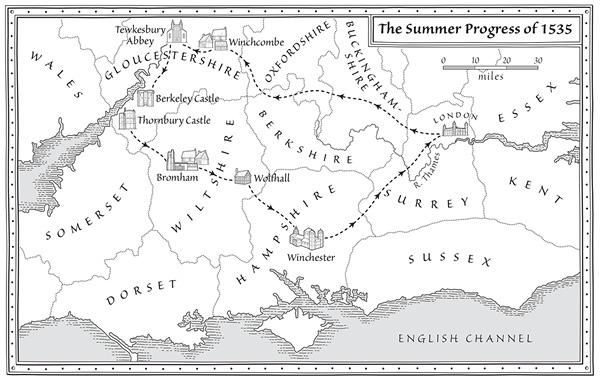

Copyright 2014 Tracy Borman Maps Rodney Paull

Cover photograph: Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, 1485-1540, after Hans Holbein the Younger , oil on panel, sixteenth century, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK/ Stefano Baldini/The Bridgeman Art Library

Author photograph by Libi Pedder Hodder & Stoughton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Hodder & Stoughton

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2317-6

eISBN 978-0-8021-9166-3

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

Also by Tracy Borman

Witches: A tale of Sorcery, Scandal and Seduction

Matilda: Wife of the Conqueror, First Queen of England

Elizabeths Women: The Hidden Story of the Virgin Queen

Henrietta Howard: Kings Mistress, Queens Servant

CONTENTS

To the other Thomas (Tom),

with love.

INTRODUCTION

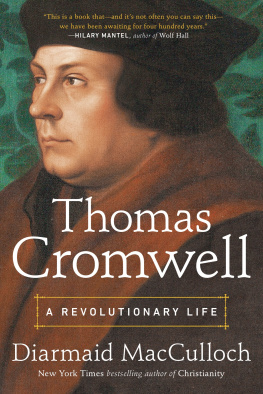

A portrait that hangs in the Frick Collection in New York has attracted more attention in recent years than ever before. Painted by the celebrated Tudor master, Hans Holbein, it depicts a man who has divided historians as much as he did contemporaries. Reviled by many as a Machiavellian schemer who destroyed Englands monasteries, ousted one queen and had another executed, and stopped at nothing in his quest for power, he has recently enjoyed a rehabilitation as an enlightened, pious and dedicated royal servant whose intelligence, wit and hospitality endeared him to friends and enemies alike. His name is Thomas Cromwell.

The publication of Hilary Mantels Wolf Hall in 2009 and its sequel Bring up the Bodies three years later took the world by storm. They inspired a sell-out season of plays by the Royal Shakespeare Company, a major television dramatisation and two Booker Prizes for the author. Mantels achievement has been to create a sympathetic and utterly compelling character out of one of historys most unlikely heroes. Her novels give us the private man behind the often notorious public faade. But how much can we really know about Cromwell? The accepted wisdom of historians has for many years been that his voluminous correspondence provides an appraisal only of the public man. Evidence of his private life, character, beliefs and outlook is at best fragmentary. As I discovered when researching my biography of Cromwell, this is a view at once misleading and inaccurate. By piecing together details found in the many letters, notes and accounts that were seized upon his arrest, a fascinating and very personal portrayal emerges of Henry VIIIs chief minister.

It is a portrayal that was only partially captured by Holbein. By the time he painted Cromwell around 1532, the artist had won justifiable renown for his skill at bringing out the character of the sitter, not just their status. Among his most celebrated works was a full-length portrait of King Henry VIII. But his portrait of Cromwell was altogether different. It is one of the most extraordinarily revealing portraits of the Tudor age. Far from flattering the sitter, it offers a brutally honest appraisal. The first impression is of a pensive and rather grumpy bureaucrat. Cromwell has a bulky frame and appears to be of middling height, although as he is seated this is difficult to judge. Turned a little to the right, his small, prying grey eyes stare intently at something in the middle distance. His eyebrows are slightly raised in a questioning, vaguely cynical stance, and his long, thin lips are pressed together in a line. The large, bulbous nose and double chin hint at the sitters age, as well as his portliness.

Although finely made of high-quality fabrics, Cromwells cap and gown are hardly the attire of a fashionable courtier. Both are in sombre black, with a brown fur collar. This may have reflected Cromwells distaste for ostentation, or it may have been a pragmatic choice. Henry VIII had laid down a strict set of guidelines to regulate dressing for court, all of which were closely tied to a persons status. The royal family alone could wear purple; dukes and marquesses could fashion the sleeves of their cloaks from gold silks; earls could wear sables; barons were entitled to a mantle of fine cloth from the Netherlands trimmed with crimson or blue velvet; and knights were permitted a shirt of damask and a collar of golden tissue. No matter how high he had risen at court by this time, Cromwell was still a man of lowly birth with none of these titles, so he was denied the privilege of wearing the rich colours and fabrics that accompanied them. He need not have chosen such plain clothes as he commonly wore, but evidence of his no-nonsense character suggests that he preferred them.

Holbeins portrait presents a compelling testament to Cromwells brilliant mind and enormous capacity for hard work. It is as if the painter has happened upon him in his study, deep in thought on some weighty matter, his expression determined. He sits on a long panelled bench or chair, behind which is a richly decorated wall. A finely bound book sits on the desk in front of him, flanked by a cluster of letters and a quill. In his left hand, which bears two large rings, he holds another letter. The scene suggests that the minister has just received a dispatch, the contents of which have required careful thought before he decided upon the appropriate response. This is no unworldly academic, but a man of action, a shrewd and decisive pragmatist driven by a desire to succeed in all things.

If Holbein achieved a convincing, albeit unforgiving portrait of an extraordinarily active and ambitious courtier, he gives little sense of Cromwells more endearing characteristics. His ready wit, brilliant conversation, irreverence and warmth are left to his own letters and the accounts of others to portray. According to Eustace Chapuys, ambassador of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whose sprawling territories included Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and parts of Italy, Cromwells awkward gait and dull air would suddenly be transformed when he was engaged in a conversation that interested him. His face would light up and take on a range of expressions from intelligent and amused to cunning and thoughtful. On such occasions, he was at his most charming, entertaining everyone present with his quick wit and warm good humour. When Cromwell made a cutting or irreverent remark, the ambassador noted that he would give a roguish sideways glance to those with whom he conversed. With chameleon-like ability, he would adapt himself to his audience and his surroundings, at turns flattering or destroying his companions with a well-directed compliment or an acerbic put-down. The sixteenth-century historian John Foxe claimed that he had suche a dexteritie of wytt as England shal skarsly have agayne. Even Cromwells enemies conceded that his social skills, charm and hospitality were second to none. Chapuys describes how the most seasoned courtiers could be completely disarmed by his pleasing manner, and lulled into saying things that they later regretted.

Next page