For George Gibson in friendship and gratitude

Contents

Introduction

The Birth of a Revolution

On September 29, 1583, swept across the eastern Atlantic. It caught the Golden Hind and the Squirrel, two ships led by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, a scientist and adventurer, as they returned to England from an expedition to plant the first English colony in North America. During the day, according to Captain Edward Hayes, master of the forty-ton Golden Hind, the waves were breaking short and high, Pyramid-wise... men which all their lifetime had occupied the Sea never saw more outragious Seas. Amid this chaos of white water, Hayes could see downwind of him the ten-ton frigate, Squirrel, that carried Gilbert.

As he watched, a furious blast of the gale suddenly threw the Squirrel on her side. At once, the Hind bore down to offer what help she could. But miraculously the tiny vessel righted herself and, to Hayess astonishment, Gilbert could be seen sitting in the stern, holding a book in his hand, and giving forth signes of Joy. As the larger ship surged past, Hayes remembered, [Gilbert] cried out unto us in the Hind, we are as neere to heaven by sea as by land.

Nothing about the valiant and learned Gilbert was predictable. A character in perpetual conflict, he contrived to be a soldier and a mathematician, openly bisexual, cruel enough to decapitate his enemies after battle then line the path to his tent with their severed heads, creative enough to imagine the growth of a new world beyond the Atlantic, and forceful enough to push through his pioneering expedition without adequate funds or manpower. Perhaps the most striking testament to Gilberts unorthodox character was his choice of a partner, Queen Elizabeths astrologer, John Dee, known as the Great Magus.

. While Gilbert adventured abroad, Dee had remained in Mortlake so that he could secretly study with his friend, Edward Kelley, how to transmute the base metal of lead into gold. But none of the Great Maguss esoteric arts possessed a power comparable to the magic that Gilbert carried to the newfound land beyond the Atlantic.

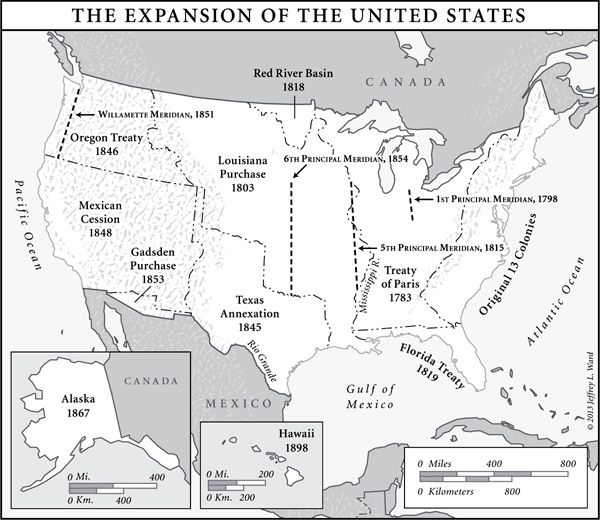

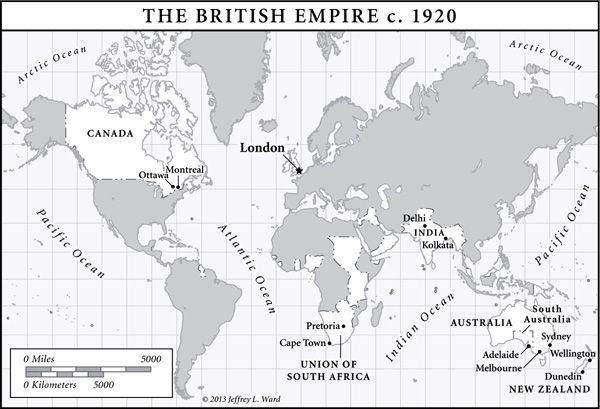

Its most obvious element was the wording of his royal charter. In response to Gilberts proposal to explore those large and ample countreys [that] extended Northward from the cape of Florida, Queen Elizabeth had given him permission to own , countries, & territories so to be discovered... with full power to dispose thereof, & of every part thereof in fee simple or otherwise, according to the order of the laws of England. Among the many different ways of possessing the earth, fee simple was, and is, tantamount to outright ownership. Any part of North America from Florida to Newfoundland not already occupied by any Christian prince or people could become his property to be sold, rented, or mortgaged as though he were in England.

A further ritual was needed to convert the wilderness into property. The land had to be measured, mapped, and registered in the name of its owner. Thus when Gilbert sailed in June with a tiny fleet of five vessels, the crew included surveyors armed with measuring poles and compasses. Although one ship commanded by his half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, immediately turned back, the remainder took the route followed for more than a century by fishermen from France, Portugal, and England to the Grand Banks off Newfoundland.

On August 5, 1583, Gilbert arrived at Saint Johns harbor to find almost forty fishing vessels already there, not only catching cod but drying and salting them onshore. Immediately the surveyors went to work, and, as Hayes put it, did observe [plans] of the countrey exactly graded [to scale]. Before the end of the month, the first transactions had taken place, and parcels of land along the waters edge were being rented out to fishermen who until then had occupied them freely. For which grounds Hayes pointed out, they did covenant to pay a certain rent and service. In return, Gilbert assured his tenants they now had the right to occupy their own particular spot from one year to the next.

On the face of it, Gilberts behavior was absurd. For uncounted generations the granite hills overlooking the long, dog-leg inlet of Saint Johns had been used by the Mikmaq people, who regarded it as their territory. The Basque fishermen who had discovered the sheltered haven perhaps before Columbus sailed to America in 1492 believed that they and any others who had the audacity to cross the ocean to fish for cod had earned the right to use the landing-grounds during the summer season. But that was as far as it went.

Yet now, under English law Sir Humphrey Gilbert asserted just such a right, and on that basis proposed to charge the fishermen rent for using a part of the wilderness for activities that they had always engaged in freely. For the first time, an idea that would revolutionize the structure of society and transform the way people thought about themselves had made itself known outside its homeland.

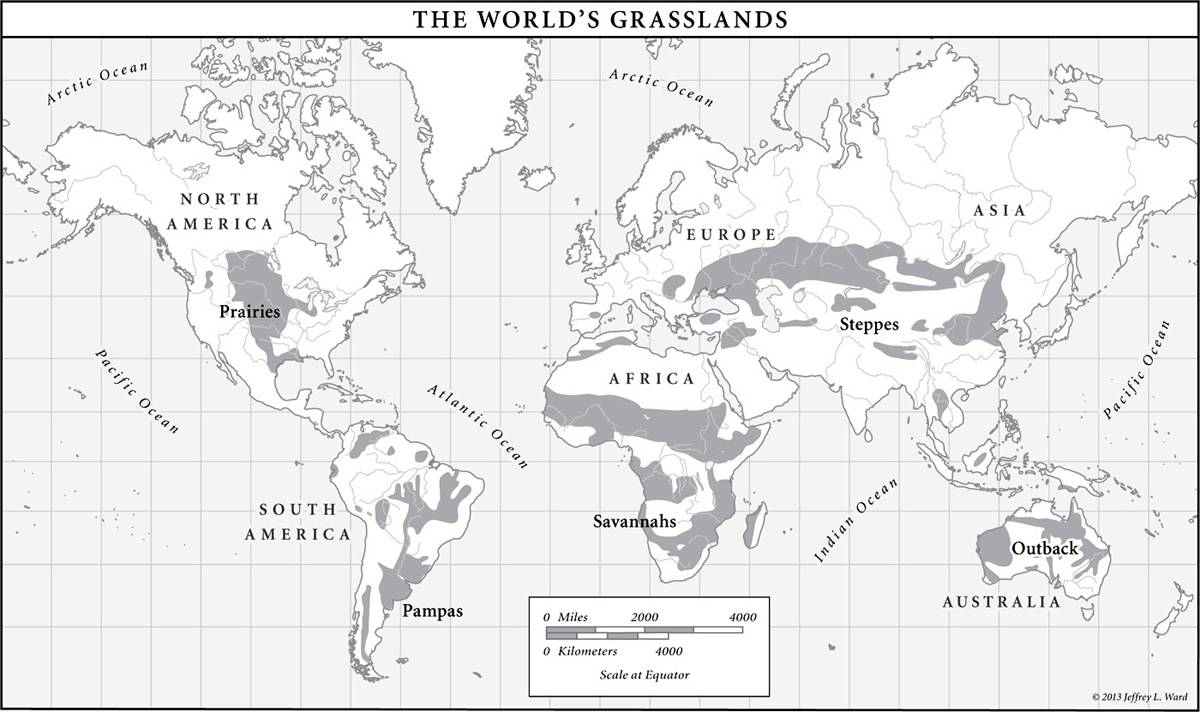

Biology underpins the pivotal influence that ownership of the earth exerts on human life. There are givens that remain as true for the nearly seven billion of us presently living here as they were for the five hundred million people scattered across the land in 1583. The bodys core temperature must remain within a degree or two of 37 degrees Celsius or 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. To maintain this temperature, of 1,800 calories a day, preferably 2,450 according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and closer to 4,000 calories for the sort of labor demanded of the fishermen in Saint Johns harbor. That adult must also be clothed and sheltered from the burning sun and freezing rain. Except for some coastal communities, the earths population in every era has always depended on the land for at least 85 percent of the energy that keeps it alive, and for all its clothing and shelter.

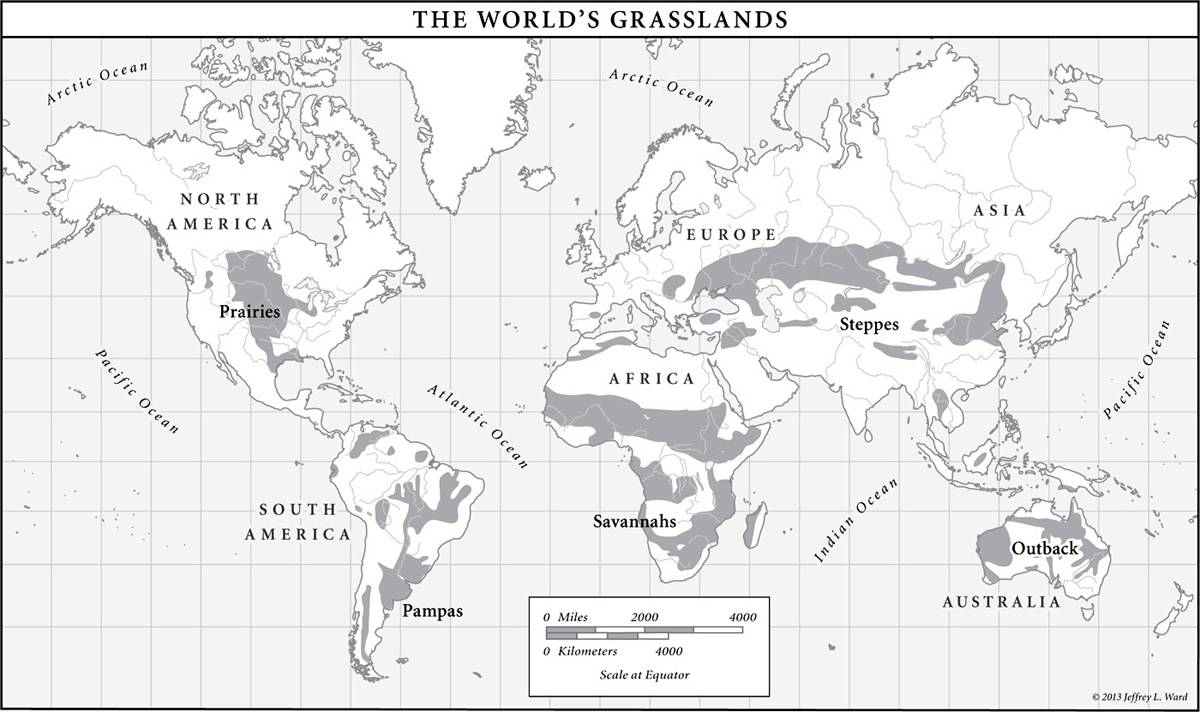

This inescapable fact of life makes forty-five million square kilometers of farmland, roughly eighteen million square miles. In optimum conditions, less than half of this area might be sufficient to produce the calories needed for survival. But the land must also produce biofuels, animal feed, minerals, timber, and cotton and other clothing fibers. At the same time, the soil degrades, cities spread, climate changes, and natural disasters such as droughts and floods, earthquakes and tsunamis, whittle away spare capacity to danger levels.

Any realistic scenario for 2050 has to consider how the earth will be owned.

In 2010, for the first time in human existence, more people lived in cities than in the country. But even in the sprawl of metal and plastic shacks that make up the slums of Kibera outside the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, or the that house a million people in the Dharavi slum in Indias Mumbai, the same fundamentals hold good. The food and sometimes the clothing may be produced elsewhere, but occupancy of a room or a corrugated iron shack is the essential base every family needs for sleeping, eating, and working, so that it will be strong enough to produce whatever labor or goods are necessary to buy a bag of rice and a T-shirt. Laying claim to the ground in some form is an inescapable condition of human existence.

Next page