Publication of this book was made possible, in part, with a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

2011 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Michelle Coppedge

Set in MT Walbaum by IBT

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stremlau, Rose.

Sustaining the Cherokee family : kinship and the allotment of an indigenous nation /

Rose Stremlau.

p. cm. (New directions in indigenous studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8078-3499-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8078-7204-8 (pbk : alk. paper)

1. Cherokee IndiansLand tenure. 2. Cherokee IndiansCultural assimilation.

3. Cherokee IndiansKinship. 4. Allotment of landGovernment policy

Cherokee Nation, Oklahoma. 5. Cherokee Nation, OklahomaHistory.

6. Cherokee Nation, OklahomaSocial conditions. 7. United StatesSocial policy.

8. United StatesRace relations. I. Title.

E99.C5S8665 2011

976.600497557dc22

2011008427

Portions of this book were published, in somewhat different form, as In Defense of This Great Family Government and Estate: Cherokee Masculinity and the Opposition to Allotment, in Southern Masculinities, ed. Craig T. Friend (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009), 6582; and To Domesticate and Civilize Wild Indians: Allotment and the Campaign to Reform Indian Families, 18751887, Journal of Family History 30.3 (July 2005): 26586.

Used by permission.

cloth 15 14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2 1

paper 15 14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

The staffs at the following libraries and archives guided me while I researched this project: the Hampton University Archives in Hampton, Virginia; the Oklahoma History Society in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; the Western History Collection at Oklahoma University in Norman, Oklahoma; the Davis Library at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; the Livermore Library at the University of North Carolina in Pembroke, North Carolina; and the southwestern branch of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Fort Worth, Texas. Staff at the Red Cross Hazel Braugh Records Center and Archives and the Cherokee Nation GeoData Center shared materials and answered my questions. Many librarians and archivists have been generous with their time and knowledge, and they have made my research more efficient and enjoyable. In particular, I thank Kent Carter, Meg Hacker, Ridley Kessler, Mary Jane Warde, Bill Welge, and Chad Williams.

Others have supported me financially through the stages of this project: the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, particularly the Royster Society of Fellows; the American Philosophical Society; the University of North Carolina at Pembroke; the American Association of University Women; and the First Peoples Initiative. The generosity of those I have never met has made this achievement possible, and I am grateful to these donors.

I am humbled by the enthusiasm for my research shown by colleagues over the years. Vernon Burton has mentored me since I was a college student, and he inspired me to become a scholar. Since the beginning of my academic career, Mike Green and Theda Perdue have struck the balance between the carrot and the stick, and I know they will be proud to read this book. The historians at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill nurtured me intellectually when this project was in its infancy, and then my colleagues in the Departments of History and American Indian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke encouraged my bringing it to completion. Over the years, respondents at many conferences have improved my analysis. Several special women have gone out of their way to support me and this project in unexpected ways at important times; thanks are due to Janet Gentes, Kathleen Hilton, Sandra Hoeflich, and Susan West.

Before I knew I could do this, Mark Simpson-Vos, my editor, believed that I could. I am glad that he was right and that I benefited from his direction and encouragement. The readers, Katherine Osburn and Margaret Jacobs, provided suggestions that enabled me to dramatically improve my work, and I hope the final product does right by their thoughtful reports. Catherine Cox worked with me to improve the manuscript, and through her feedback, I first saw this project as whole.

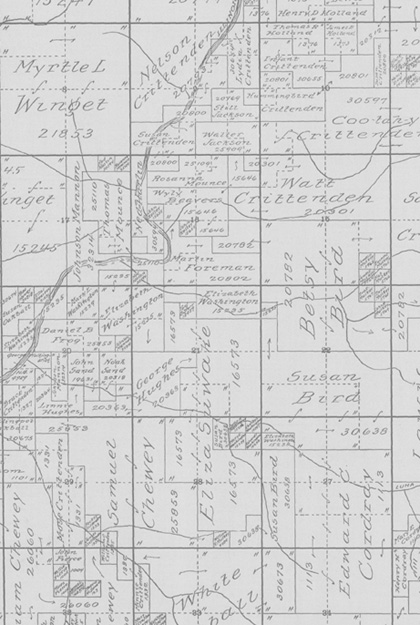

Before I began researching allotment in the Cherokee Nation, I had never been to Oklahoma. A friend from there told me that Oklahomans are the most down-to-earth, hospitable people I could ever know. Over the years, I have found this to be true. Many improved this manuscript with their enthusiasm, and I am deeply appreciative. Bill Welge, a living encyclopedia of Oklahoma history, read an entire draft of this book. I appreciate his feedback and support. Special thanks go to members of the Goingsnake District Historical Association who shared information and stories about their ancestors. Several years ago, Gail Crittenden sent me copies of photographs from her collection. When I opened her package, I saw the faces of the people about whom I was writing for the first time. I am grateful for that kind gesture. Several Cherokee scholarsespecially Julia Coates, Wyman Kirk, and Benny Smithprovided feedback and insight. Jack D. Baker deserves special thanks. Many years ago, he suggested to Perdue and Green that someone should write about allotment among Cherokees. When that someone became me, he encouraged and supported my research, which included telling me what I got wrong. I would not have started this project without Jack, and, without question, I could not have finished it without him. Likewise, Richard Allen thoughtfully critiqued the manuscript. I am honored that he took the time and effort to share his honest thoughts, and I am glad that he delivered them with humor and kindness.

I could not have finished this project without a circle of supportive scholars who have become dear friends. My early writing group mates, Pam Lach and Barb Hahn, celebrated each small accomplishment with me over sangria swirls at Los Pos in Chapel Hill, and their feedback and counsel enabled me to rediscover pleasure in a process that had become a struggle. Jaime Martinez and Ryan Anderson have continued in this tradition of combining feedback and fellowship with good results. The friendship of Charles Beem, Jane Haladay, Mary Ann Jacobs, Malinda Maynor Lowery, and Cary Miller has been one of the best rewards of my chosen profession. My dearest old friend, Angie Oliver, regularly reminded me that I had a life before this project and that I would have one again after I completed it. She and my parents have weathered the highs and lows of this whole process no less than I have done. For the last dozen years, Leon and Rosemary Stremlau have encouraged me with their cheer, a line from a favorite old movie. I love the irony of my northerner parents motivating their daughter, who has made her home in the South and who is writing a book on American Indian history, by shouting out a line from a John Wayne movie in which he played an angst-ridden Union general: Get er done, Johnny Reb! Get er done! And so I did.