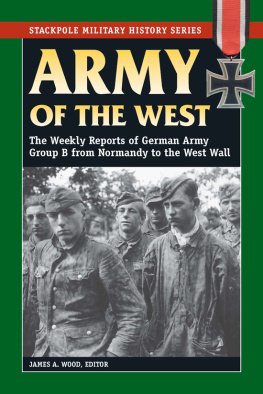

General Lesley J. McNair

MODERN WAR STUDIES

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor

Raymond Callahan

J. Garry Clifford

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

Dennis Showalter

David R. Stone

Series Editors

General

Lesley J. McNair

Unsung Architect of

the US Army

M ARK T. C ALHOUN

2015 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Calhoun, Mark T.

General Lesley J. McNair : unsung architect of the US Army /

Mark T. Calhoun.

pages cm. (Modern war studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-2069-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2070-8 (ebook)

1. McNair, Lesley James, 18831944. 2. GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. 3. United States. ArmyOfficersBiography. 4. Military educationUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. United States. ArmyOfficersTraining ofHistory20th century. 6. SoldiersTraining ofUnited StatesHistory20th century. 7. World War, 19391945--United States. 8. World War, 19141918Biography. 9. World War, 19391945Biography. I. Title.

E745.M42C45 2015

355.0092dc23

[B]

2015002822

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials z39.481992.

For Mark Taylor Calhoun Jr.

Contents

Illustrations

Frontispiece:

Preface

Many historians advised me not to pursue this topic for my first book, mostly because of their concern that insufficient archival records existed to support a detailed analysis of Lesley McNairs career. I did receive encouragement from a few individuals, but most reminded me that no single source of McNair Papers exists, and they warned me that I would have to visit many different archives in hopes of finding adequate sources, risking much on the conviction that such records existed. Despite this well-intentioned advice, I stubbornly continued my potentially fruitless questand through a combination of luck, persistence, and the help of many talented archivists and supportive colleagues, I managed to amass a much larger collection of papers than I ever imagined I would.

When I first began to discuss with colleagues and friends my desire to work on this topic, I heard an often-repeated story, which soon took on the form of folk wisdom. It always centered on an unnamed graduate student who had supposedly begun work on a dissertation on McNair but could not complete it because he could not find adequate sources. After much searching for this mysterious graduate student, I finally found one historian who thought he knew who it might be. This historian had a student some years hence that did intend to write his dissertation about Lesley McNair, but he dropped out of his PhD program for personal reasons in his first year, before he even began to conduct dissertation research.

I also often heard the rumor that Clare McNair, Lesleys wife of nearly forty years, burned his papers out of grief in 1944, after her husband died in Normandy, and only twelve days later, their only son, Doug, died in Guam. I soon found evidence that she did not burn her husbands papers. In 2010, I discovered a set of McNair papers at the Library of Congress. The first of the nine boxes included a short letter that Clare McNair wrote when she donated the papers. This collection consisted of various personal items including letters, poster-sized promotion orders (sheepskins), and several scrapbooks of photos and newspaper clippings that Clare collected throughout her husbands career. Interestingly, the letters in the collection of personal papers include none between Lesley and Clare (or between McNair and any family members or colleagues); they consist entirely of Clares communications with friends of the family and Lesleys professional acquaintances. However, no evidence exists that Clare selectively destroyed any of Lesleys personal records or letters. The collection appears complete, with no chronological gaps or signs of Clare removing any documents from the scrapbooks or other collections.

Army personnel who worked with McNair soon learned of his habit of working long hours and doing little else. One can see this aspect of his personality in the documents he left behind, as they consist almost exclusively of professional correspondence. He rarely wrote personal letters (and those few located in various archives usually address both business and personal matters). He also did not maintain a journal or diary, although he did accumulate a small collection of articles and board reports related to projects that he worked on throughout his career. These files now reside in Record Group 337 at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland (NARA 2). An exhaustive search turned up no more personal files or correspondence at other archives than those located at NARA 2.

Another fact helps explain the lack of personal correspondence in archival collections of McNair papers. He spent most of his career, and nearly all of World War II, in stateside assignments. Although he worked long hours, he lived at home and saw Clare regularly, and therefore he did not need to maintain a lengthy written correspondence with her. If he exchanged letters with her during any of his early career deployments (the Vera Cruz Expedition, the Punitive Expedition, and World War I), they apparently did not find their way to an archive. One aspect of this lack of personal correspondence seems rather odd: the absence of letters to Doug McNair, his only child and fellow artilleryman who served during World War II, both stateside and overseas. McNair appears to have kept track of his sons career indirectly, through correspondence with colleagues who had regular contact with him. No evidence exists that he corresponded with Doug directlyat least not regularly. This probably merely serves as an example of McNairs formal demeanor, which might have led him to see Doug first as a junior army officer and then as a son. (This formality comes across, at least, in the few letters located in various archives that he wrote to Doug, or in which he mentioned him.) The reliance on his wife to handle their social correspondence fits with McNairs businesslike demeanor, as well as with the culture of the era, but his limited interaction with his son seems indicative of an unusually formal, even distant, attitude toward personal relationships.

McNair also generally avoided the public eye. He disliked engaging the media, and he did not do so regularly until his duties during World War II required it. He exhibited no interest in fame or notoriety. One can only speculate whether he might have produced a memoir had he survived the war, like so many of his peers did, but no evidence exists that he began work on one during his career. While the various archives cited in the bibliography collectively contain a great deal of material on McNairs careermost of which does not appear to have been used in any previous secondary workthey consist almost exclusively of official documents. This book therefore serves as an analysis of one army officers career and the impact that he had on the armys effectiveness in the caldron of battle during World War II. It contains minimal biographical information, instead focusing on McNairs military life. It provides the first comprehensive analysis of McNairs duties, professional experience and performance, and development as a military leader and thinker over the full forty years of his career. Most importantly, this study identifies the connections between McNairs key formative experiences during his early career and the thinking that guided his actions during his last five years of service, when he rose to the highest levels of rank and responsibility of his career and made a significant impact on Americas war effort from 1939 to 1944.

Next page