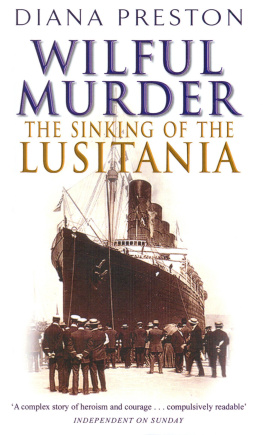

Diana Preston is an acclaimed historian and author of the definitive Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy , Before the Fallout: From Marie Curie to Hiroshima (winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Science and Technology), The Boxer Rebellion , and The Dark Defile: Britains Catastrophic Invasion of Afghanistan, 18381842 , among other works of narrative history. She and her husband, Michael, live in London.

As always I am grateful to Michael, my husband and coauthor, without whom this book would not have been written.

I would also especially like to thank the following for giving generously of their time and expertise: Dr. Tim Cook, Canadian War Museum; Dr. Janet Howarth, St. Hildas College, Oxford; Kim Lewison, Neil Munro; Professor Holger Nehring, University of Stirling; Paddy OSullivan, Dirk Ullmann, the Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft; Donald Wallace FRCS, Dr. Ingrid Wallace, and Dr. Mike Wood.

In the United Kingdom the help of the staff of the British Library; the London Library; the Bodleian Library; Churchill College, Cambridge; the National Maritime Museum; the Merseyside Maritime Museum; the National Archives; the BBC Written Archives Centre; and the Cunard Archives was invaluable. I am also very grateful for the insights of Lusitania survivor Audrey Lawson-Johnson, ne Pearl, and Joe Wynne for his recollections of George Wynne. In the United States I must thank the staff of the Library of Congress, the National Archives and Records Administration, the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, and the Mariners Museum, Newport News, Virginia. In Canada, I am indebted to CBC for access to taped interviews with Lusitania survivors and to the staff of the Canadian War Museum. In Ireland I much valued the assistance of the Cobh Museum and the National Maritime Museum and in Germany the help of the archivists of the Militrarchiv, Freiburg, and of Bernd Hoffmann of the Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin.

I would like to thank my mother, Florence Faith, for all her many years of encouragement.

I also much appreciate all the help, advice, and encouragement of my agents Bill Hamilton in London and Michael Carlisle in New York and of George Gibson and all his team at Bloomsbury.

Appendix

In April 1918, a New York judge, Julius Mayer, heard claims for negligence against Cunard by survivors or relations of the Lusitania s American victims. During preliminary discussions between lawyers the plaintiffs agreed to drop allegations that the ship had been armed and carrying clandestine ammunition and Canadian troops, all of which, if proven, would have considerably aided their case. Judge Mayer said simply, That story is forever disposed of.

Statements were taken from, or evidence given by, many people, including Captain Turner. Several passengers confirmed portholes had remained open despite Captain Turners instructions to close them. Much further evidence was given on the cargo. An expert from Remington stated that neither fire nor impact could have caused the rifle cartridges aboard to explode. A representative from Bethlehem Steel confirmed the shrapnel cases were unfilled and that the separate consignment of fuses did not contain any explosives. On torpedoes, witnesses said there had been from one to three, with most suggesting two. Wesley Frost, the U.S. consul in Queenstown whose report to the State Department had unambiguously stated that the Lusitania was sunk by one torpedo and had collected numerous statements from American survivors on which he based his view, was not called to give evidence. Nor did the State Department volunteer to make available the passengers statements.

Judge Mayers opinion, handed down on August 23, 1918, absolved Cunard and Captain Turner from blame: The cause of the sinking of the Lusitania was the illegal act of the Imperial German Government, acting through its instrument, the submarine commander, and violating a cherished and humane rule observed, until this war, by even the bitterest antagonists. Mayer also ruled that no materials had been carried that could be exploded by setting them on fire in mass or in bulk nor by subjecting them to impact. He agreed with Lord Merseys erroneous conclusion that there were two torpedoes, declaring the weight of the testimony (too voluminous to analyse) is in favour of the two torpedo contention and that as there were no explosives on board it is difficult to account for the second explosion except on the theory that it was caused by a second torpedo.

On Captain Turners conduct Mayer concluded, The fundamental principle in navigating a merchantman whether in times of peace or of war is that the commanding officer must be left free to exercise his judgement. Safe navigation denies the proposition that the judgement and sound discretion of the captain of a vessel must be confined in a mental straitjacket.

Despite Judge Mayers conclusions that some issues were forever disposed of, this did not prove to be the case. Controversies about the Lusitania have continued to this day, only partially resolved by dives on the wreck, in particular that by Bob Ballard and his Woods Hole team, backed by National Geographic , in 1993 using remotely controlled submersibles with modern video and lighting equipment.

Some writers have quoted Churchills comments of February 1915 to Walter Runciman, president of the Board of Trade, that it is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores in the hope especially of embroiling the USA with Germany. They link these words with the limited efforts made to warn or protect the Lusitania to suggest that Churchill deliberately conspired to expose the Lusitania to bring the United States into the war. The kaiser on some occasions subscribed to this theory. Nearly a year after the sinking, he told U.S. ambassador Gerard that England was really responsible as the English had made the Lusitania go slowly in English waters so that the Germans could torpedo it and so bring on trouble.

However, there is no evidence of any such conspiracy. The general consensus at the time in the British government was that it was better to maintain the United States as a friendly supplier of munitions, rather than have it enter the war and wish to have a large say in dictating the peace. Rather than conspiring, the Admiralty appears to have been complacent, almost to the point of negligence, in disregarding information that the Lusitania was a German target (including the New York newspaper warning) and trusting in the Lusitania s speed to get her through without taking any protective measures. Such complacency is partially explained by Churchill and Fisher being distracted by the foundering Dardanelles/Gallipoli campaign over which they were at loggerheads.

There is, however, clear evidence that after the sinking the British government, concerned not to forfeit any part of the propaganda advantage, conspired first to place the blame on Captain Turner for putting his ship at risk, and then to explain away the widely reported second explosion by attributing it to a second torpedo when they knew definitely from the message intercepted by Room 40 that there had only been one. The U.S. administration, unsurprisingly at the time of the Mayer hearing when the United States was in the war, took no action to disturb this conclusion despite the considerable information it had to the contrary.

When he realized the damage world outrage was causing to his and Germanys reputation, the kaiser said that he would not have authorized the sinking with the resultant deaths of so many women and children had he known in advance. At the same time the German authorities continued illogically to justify the sinking on the grounds of Lusitania s alleged armament and carriage of Canadian troops and of munitions. They did not recognize the inconsistency that if Schwieger had not known which ship he was attacking he could hardly have known her armament, cargo, or passenger list, thereby invalidating any justification based on them. The reality is that the Lusitania was an acknowledged target for the German U-boat service. Her name appears the most frequently in the merchant shipping targets identified in the German telegrams decoded by Room 40. U-boat commander Bernhard Wegener did not doubt that she was an authorized target when he lay in wait for her in the U-27 in Liverpool Bay in March 1915. He recorded his actions carefully in his war diary stating he was following guidance from Half-Flotilla Commander Hermann Bauer. He signed off his war diary for each day of the cruise. It was circulated as normal and he was not rebuked or told he was wrong to target the Lusitania .

Next page