Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

ALSO BY RICHARD RHODES

Hedys Folly

The Twilight of the Bombs

Arsenals of Folly

John James Audubon

Masters of Death

Why They Kill

Visions of Technology

Deadly Feasts

How to Write

Dark Sun

Nuclear Renewal

Making Love

A Hole in the World

Farm

The Making of the Atomic Bomb

Sons of Earth

The Last Safari

Looking for America

Holy Secrets

The Ozarks

The Ungodly

The Inland Ground

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2015 by Richard Rhodes

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition February 2015

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Akasha Archer

Jacket design by Thomas McKeveny

Jacket art work: Guernica , 1937 Pablo Picasso Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain/Bridgeman Images

Jacket art work 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4516-9621-9

ISBN 978-1-4516-9623-3 (ebook)

For Stanley Rhodes, 19362013

A grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation supported the research and writing of this book.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

E rnesto Vinas, a tall, ruggedly handsome man in his late thirties, a husband and father, lives on the edge of an old battlefield in the small Spanish town of Brunete, fifteen miles west of Madrid. In 1937, in the heat of Spanish summer, thousands of young men died at Brunete, one side defending the Spanish Republic, the other side fighting for Francisco Franco and the generals he led in rebellion. Ernesto is a dental technician, but he knows more about the battle of Brunete than anyone else in the world.

Ernesto mastered Brunete from the ground up. Curious about a battle fought decades before he was born but only blocks from his door, he started searching the battlefield with a metal detector. Seven decades had embedded the Brunete debris, but the metal detector found some of it: bullet casings, badges, belt buckles, shell fragments, empty grenades. The iron objects were blistered with rust, the brass and copper sulfated gray-green. Ernestos trowel uncovered more, calcined a chalky gray and dirt-dusted: eyeglass frames, toothbrushes, nests of carpals, shards of femur, shells of skull. Flesh had weathered until only what was hard remained, a flattened and scattered map.

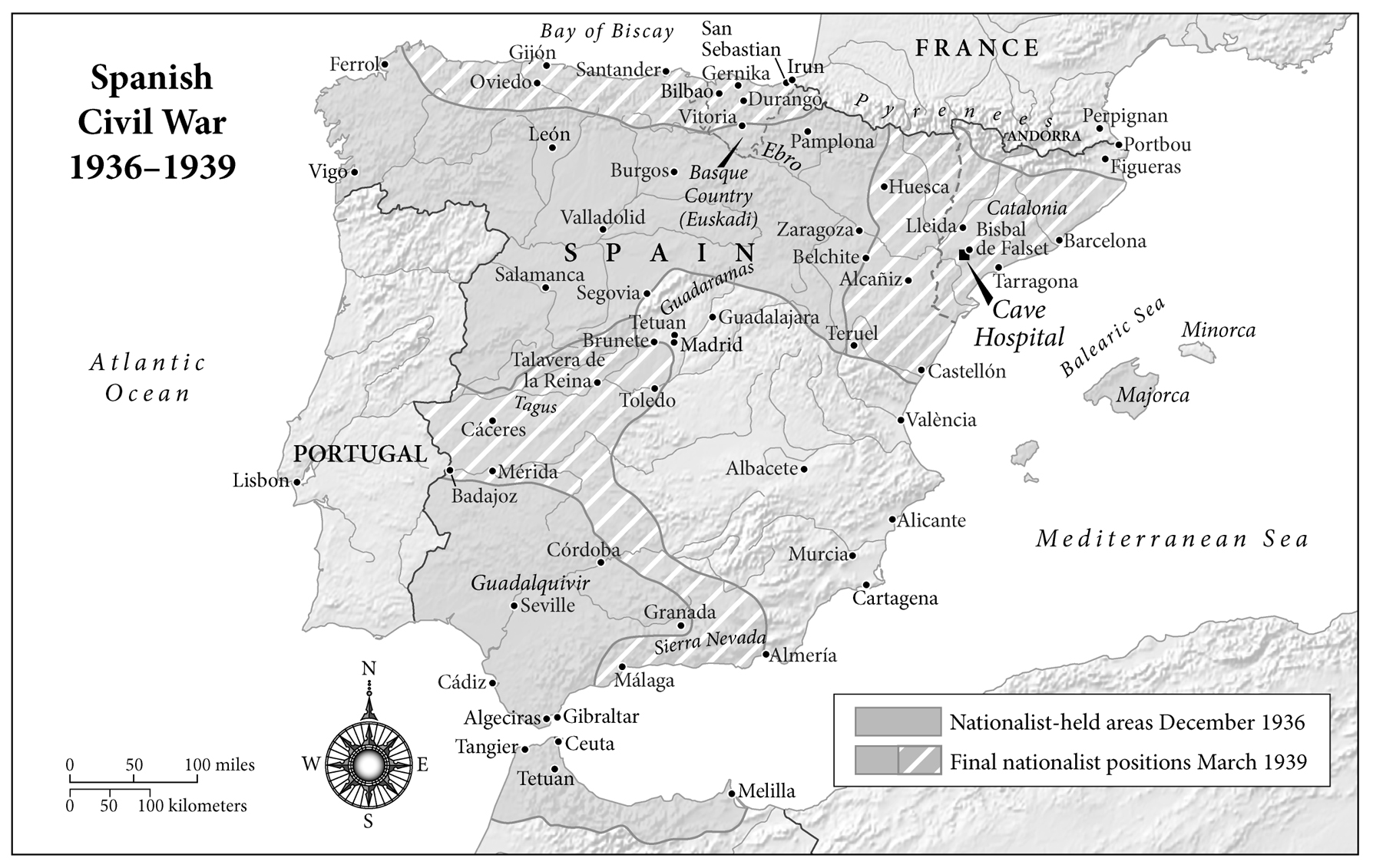

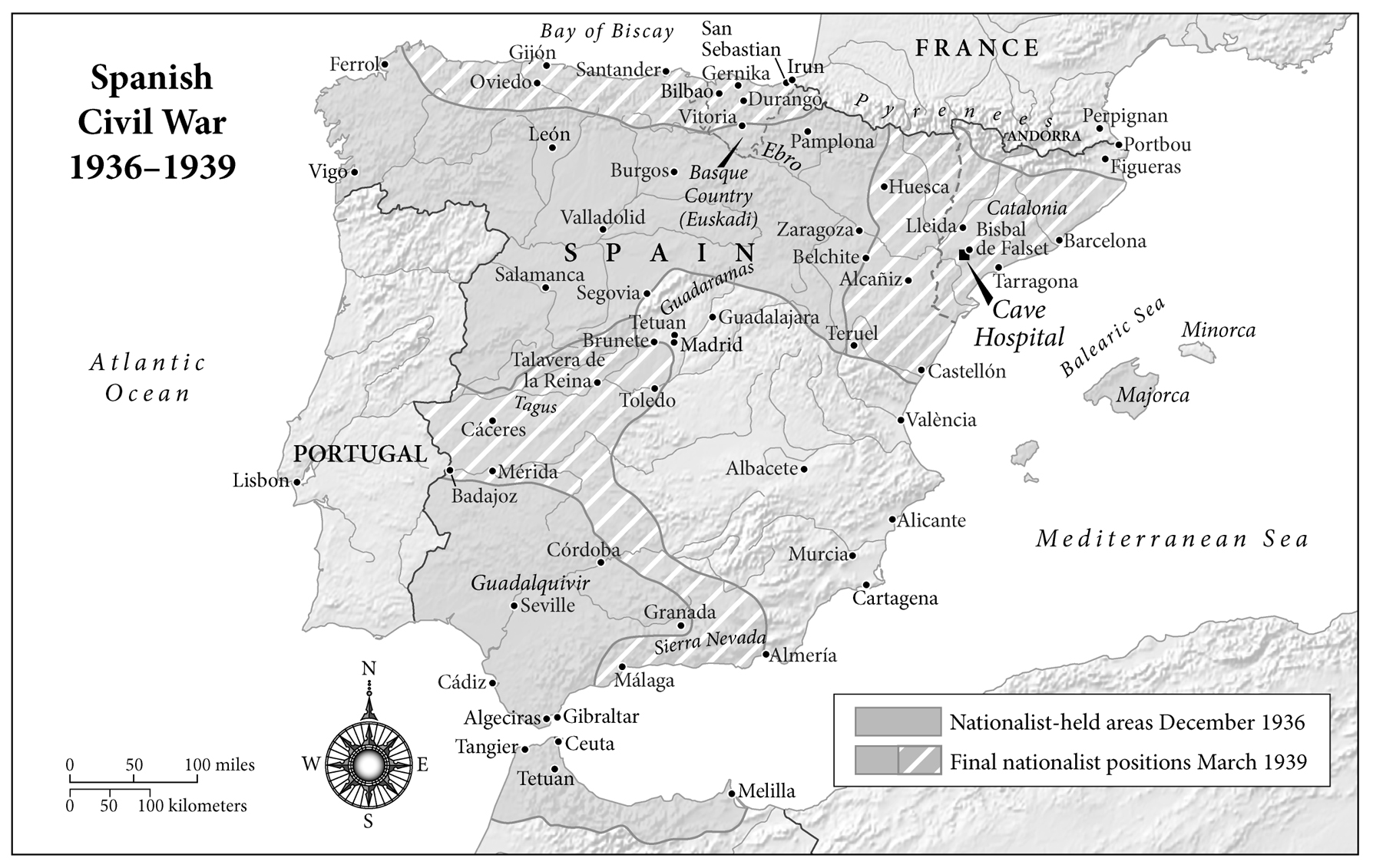

I toured the battlefield with Ernesto one brisk, sunny day in October. Afterward, he led me down into his basement, where his years of collections were arrayed floor-to-ceiling on white shelvesthousands of relics of metal and bone. I photographed the grenades, some of the badges, and particularly the burned-out casings of incendiary bombs. Those bore German markings: in April 1937 the German Luftwaffes Condor Legion had rained down similar bombs on the Basque village of Gernika, to the worlds outrage and Picassos inspiration.

Ernestos collecting had been a beginning for him. He had paralleled it with reading, visits to the archives, and discussions with veterans. So did I. All the veterans are gone now, but many left recollections. At New York Universitys Tamiment Library I found folders filled with them, never published, brown with age. World War II began in Europe only five months after the Spanish struggle ended, in 1939, and the war in Spain that had been a laboratory for the larger war and a test bed for the best and worst of its technologies was all but forgotten.

Spain had convulsed with civil war between 1936 and 1939 when her generals had revolted against a government determined to retire them from their positions of well-upholstered privilege. The ambition of every Spanish general, writes the Spanish diplomat and historian Salvador de Madariaga, is to save his country by becoming her ruler. Spain had suffered from an excess of generals since the turn of the twentieth century, when the loss of her colonies in the Philippines and Cuba in the Spanish-American War had sent them crowding home.

At the beginning of the 1930s the long-suffering Spanish people had finally laid claim to a share of their countrys natural wealth, wealth that the landed nobility for centuries had colluded with the military and the Catholic Church to hoard. Turning against a military dictatorship allied with King Alfonso XIII, popular leaders had proclaimed a republic, deposed the dictator, and forced the king into exile. The Spanish Republics new constitution endowed universal suffrage, public education, land redistribution, and Church disestablishment. From 1931 to 1936, the Republic struggled to improve its peoples lives during the worst years of the Great Depression even as it fought off first an armed revolt of the Right and then an armed revolt of the Left. The civil war that began in July 1936 was another and final armed revolt of the Right, led by yet another general, Francisco Franco, who then ruled Spain as its absolute dictator for more than three decades until his death in 1975.

Many books have been written about the Spanish Civil War. Few of them explore the aspects of the war that interest me. This book only incidentally concerns Spanish politics. Spain today is a democracy. Who was a communist, who a fascist, who connived with whom in the Spanish labyrinth are questions for academics to mull. I was drawn, rather, to the human stories that had not yet been told or had been told only incompletely. I was drawn as well to the technical developments of the war. If destructive technology amplifies violence, constructive technology amplifies compassion, and the lessons of technology are universal.

Some of the innovative technologies of the Spanish war still have direct application today. Spanish and foreign volunteer doctors made medical advances in blood collection, preservation, and storage; in field surgery; in the efficient sorting of casualties. Fortuitously, these innovations came just in time to save lives not only in Spain but worldwide, among combatants and civilians alike, in the larger war that followed. The Catalan physician Josep Truetas method of cleaning, packing, and then protectively casting large wounds in plaster was recently independently rediscovered; in its new incarnation, as vacuum-assisted wound therapy, it is preserving limbs that organisms resistant to antibiotics might otherwise destroy.

Next page