ON THE DAY, nearly a decade ago, when I first pulled Alice Bacons A Japanese Interior from its basement shelf at the New York Society Library, I never imagined the voyage it would send me on, or the extraordinary people I would meet along the way.

Several descendants of the protagonists and their families shared stories and artifacts and provided a living link to the past: Jean Bacon Bryant, Akiko Kuno, Michio Tsuda, Setsuko Uriu, Yvonne Ying-yue Yung. Three generations of Tsuda College alumnae in the Fujita family shared their perspective on how the school has evolved across the decades.

Sachiko Tanaka and Takako Takamizawa were the fairy godmothers of my research in Tokyo, providing critically important encouragement and access. Librarians and archivists unlocked trove after trove of letters, documents, and photographs, especially Akira Sugiura and Yuki Nakada of Tsuda College, Dean M. Rogers of Vassar, James W. Campbell of the New Haven Museum, Rie Hayashi of the International House of Japan, Fernanda Perrone of Rutgers, and Brandi Tambasco of the New York Society Library.

Many experts, friends and strangers both, were startlingly generous with insights and advice: Margaret Bendroth, Lesley Downer, Elisabeth Gitter, Robert Grigg, Ann Havemeyer, James Huffman, James Lewis, James Mulkin, Anne Walthall, Barbara Wheeler. Special thanks to Daniel Botsman, chair of the Council on East Asian Studies at Yale, whose extensive and thoughtful comments were a gift.

For close reading (and close friendship) I am grateful to Jessica Francis Kane, Gail Marcus, Zanthe Taylor, Carlton Vann, and Isaac Wheeler.

This project would never have become a book without Rob McQuilkin, who makes the most extravagant promises and keeps them; and Alane Salierno Mason, whose editorial wisdom never falters. The indefatigable Stephanie Hiebert devoted countless hours to the details. Nancy Howell drew the beautiful map.

My profoundest thanks go to Yuzo Nimura, tireless researcher, translator, and father-in-law. My work would have been impossible without him.

But the true inspiration for this book is my husband, Yoji Nimura, who took me to the other side of the world, and our children, Clare and David, who brought us back again. Home is wherever you are.

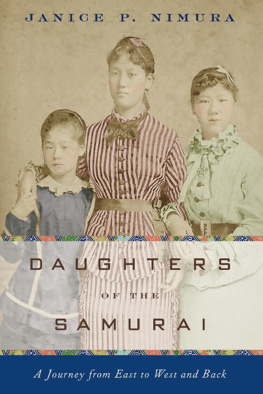

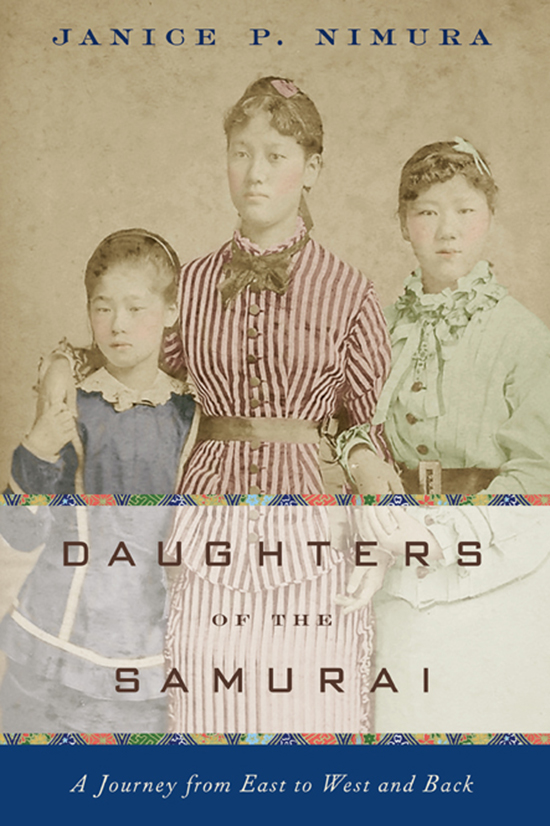

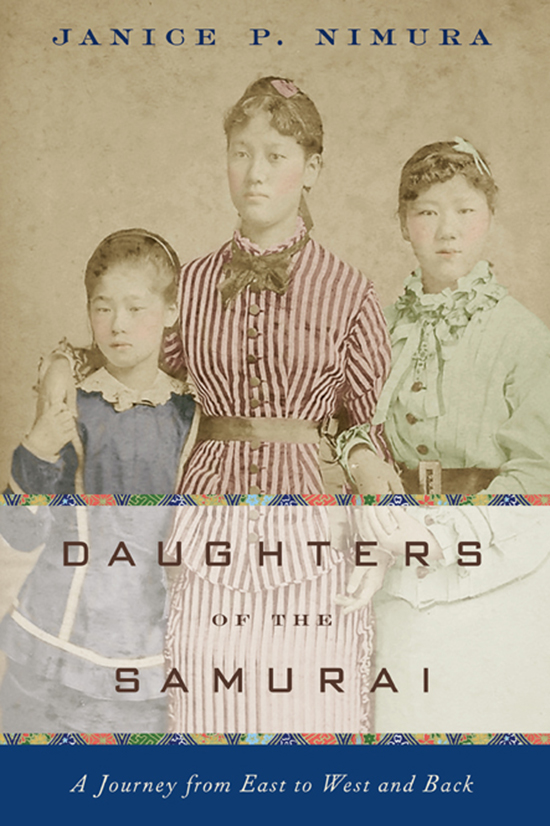

THIS IS THE STORY of three girls who were born in one world and sent, by forces beyond their comprehension, to grow up in an entirely different one. There, like all children, they absorbed the lessons of their surroundings. Though they were, each of them, purebred daughters of the samurai, they became hybrid by nurture. Ten years later, they returned to a homeland grown alien in their absence.

I live in the city where I was born, like my parents and grandparents before me. But my story converges with the one Im telling. On the first day of college, I met a boy who was born in Japan. His family had left Tokyo for Seattle when he was very small, and announced their decision to return home when he was sixteen. For him, home was America. They left, and he stayed.

Two years after our graduation and two months after our wedding, we moved to Tokyo ourselves. In many ways, my sojourn there was easier than my husbands. As my Japanese improved, I was praised for my accent, my manners, my taste for sea urchin and pickled plums. My face excused me from my failuresI was a foreigner, after all. My husband enjoyed no such immunity. He looked Japanese, he sounded Japanesewhy didnt he act Japanese?

Upon our return to New York three years later, I went to graduate school in East Asian studies and fell into a fascination with Meiji-era Japan, the moment when the Land of the Gods wrenched its gaze from the past and turned toward the shiny idols of Western industrial progress. One day, in the basement stacks of a venerable library, I found a slim green volume titled A Japanese Interior , by Alice Mabel Bacon, a Connecticut schoolteacher. It was a memoir of a year she had spent in Tokyo in the late 1880s, living with Japanese friends, known long and intimately in America. This was strange. Nineteenth-century American women didnt generally have Japanese friends, certainly not ones they had met in America.

Alice came from New Haven, where I had spent my college years; she moved to Tokyo and lived not among foreigners, but in a Japanese household, as I had; she taught at one of Japans first schools for girls, founded within a year of the one I attended in New York a century later. She wrote with a candid wit that reminded me of my own teachers, unfussy bluestockings with no patience for pretension. Following where Alice led, I discovered the entwined lives of Sutematsu Yamakawa Oyama, Alices foster sister and the first Japanese woman to earn a bachelors degree; Ume Tsuda, whose pioneering womens English school Sutematsu and Alice helped to launch; and Shige Nagai Uriu, who juggled seven children and a teaching career generations before the phrase working mother was coined.

I recognized these women. I knew what it felt like to arrive in Japan with little or no language, to want desperately to fit into a Japanese home, and at the same time to chafe against Japanese attitudes toward women. I had a husband who did not see the world through a Japanese lens, though his parents had never meant to raise an American child. A hundred years before globalization and multiculturalism became the goals of every corporation and curriculum, three Japanese girls spanned the globe and became fluent in two worlds at onceother to everyone except each other. Their story would not let me go.

In addition to the primary and secondary sources listed individually in this Bibliography, I drew upon letters, diaries, photographs, and printed material from the following archives: Bacon Family Papers, Yale University Manuscripts and Archives; Houghton Library, Harvard University; Terry and Bacon Family Papers, Connecticut Historical Society; Sutematsu Yamakawa Oyama Papers, Vassar College Library Special Collections; Tsuda College Archives, Tokyo; Whitney Library, New Haven Museum; William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University. Frequently cited archival sources are abbreviated in the notes as follows:

BFP Bacon Family Papers

SYOP Sutematsu Yamakawa Oyama Papers

TCA Tsuda College Archives

VSC Vassar College Library Special Collections

YMA Yale University Manuscripts and Archives

Newspapers and magazines of the periodespecially the Atlantic Monthly , Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper , Harpers Weekly , the New York Times , the San Francisco Chronicle , the Washington Evening Star , and Daily National Republican provided important context for the world the girls encountered in America, including lavish coverage of the Iwakura Missions movements in 1872. Meiji periodicalsincluding the Japan Weekly Mail , the Japan Advertiser , the Far East , and Shinbun Zasshi also proved invaluable in their coverage of the three women after their return to Japan.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Abbott, John S. C. The Mother at Home; or The Principles of Maternal Duty . New York: American Tract Society, 1833.

Alcock, Rutherford. The Capital of the Tycoon: A Narrative of a Three Years Residence in Japan . London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1863.

Annual Report of the Board of Education of the New Haven City School District, for the Year Ending August 31, 1874 . New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1874.

Bacon, Alice Mabel. In the Land of the Gods: Some Stories of Japan . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1905.

Bacon, Alice Mabel. Japanese Girls and Women , rev. ed. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1902. First published 1891.

Bacon, Alice Mabel. A Japanese Interior . Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1894.

Next page