There are many people and institutions that have contributed to the realization of this book. These include writers, historians and teachers, as well as museums and historical societies in Japan. The author is particularly indebted to those following for their invaluable inspiration, ideas, and support, without which this book would not have been possible. Names are listed alphabetically.

John Bonow, George L. Cohen, Minako Cohen, Suiken Fukunaga, Michio Hirao, Mitake Katsube, Mamoru Matsuoka, Saichiro Miyaji, Tae Moriyama, Mariko Nozaki, Tsutomu Ohshima, Kiyoharu Omino, Kan Shimosawa, David Stern, Tokyo Ryoma-kai.

AUTHORS NOTE

FROM THE FIRST EDITION

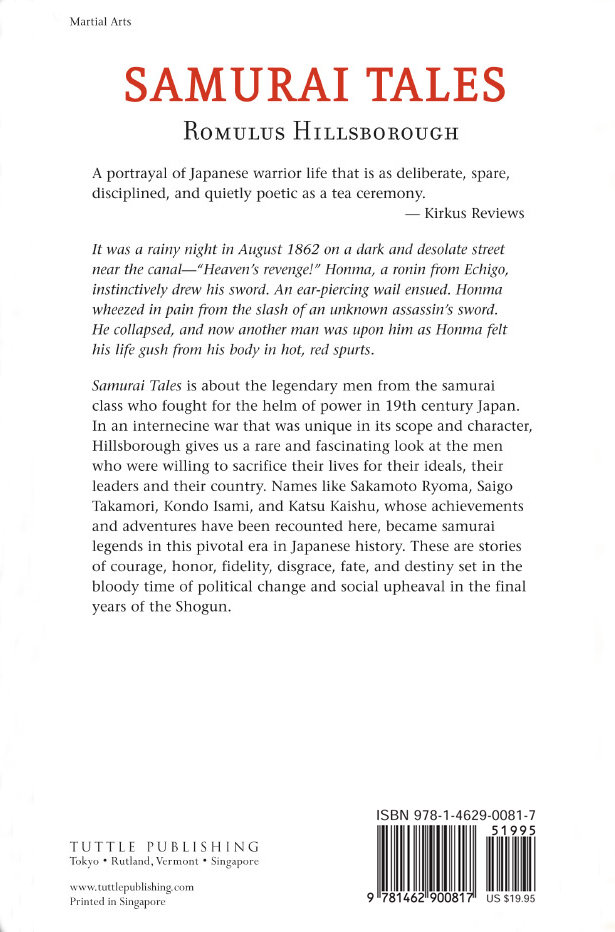

Each tale herein is a separate story in and of itself. In telling the tales collectively, however, it has been my wider objective to coherently, though briefly, recount the great epic that was the dawn of modern Japan. Accordingly, the reader will find that the circumstances, both historical and situational, laid out in previous stories do much to elucidate those of subsequent ones. It is therefore recommended that these tales be read in the sequence they appear. To provide a clearer understanding of the overall tapestry of these complicated times, I have included A Brief Historical Background of the Meiji Restoration . It is a summary of the historical, political, and social mindset wherein these samurai lived and died. Kiyoharu Omino, a distinguished Japanese historian and sword specialist, has been generous enough to write the introduction, On the Samurai, which I have translated. It is a terse, insightful exposition on Japans two-sworded class, written with the Western reader in mind and providing important information not otherwise available in the English language.

Writers of history of a distant period must depend almost entirely on recorded information, augmented perhaps by oral tradition, and aided, hopefully, by a vivid imagination. Accordingly, I hereby qualify every historical fact written herein with the statements it has been written that or it is generally assumed that, which, for obvious reasons, I have omitted in the text.

As in my previous books, for the sake of authenticity I have placed Japanese family names before given names, and used the Chinese calendar rather than the Gregorian one to preserve the flavor of the mid-nineteenth century. I have Romanized Japanese terms when I felt that translation would be syntactically awkward or semantically incorrect. Romanized terms other than proper nouns are italicized, except for those words, such as samurai and kimono, which are included in the lexicon of modern American English. I have translated proper nouns that lend themselves favorably to an English rendering. I have not necessarily adhered to standard translations of terms that have been handed down by past writers of things Japanese. Japanese terms have not been pluralized, because their Anglicization, I feel, would appall the Japanized ear.

In anticipation of a common question, I have not included a bibliography because most of my references have been Japanese works. Their titles would therefore be meaningless to a readership unfamiliar with the Japanese language. Works in the English language that I have referred to include A Diplomat in Japan (Sir Ernest Satow), Bushido (Inazo Nitobe), Samurai and Silk (Haru Matsukata Reischauer) and The Samurai Sword (John Yumoto).

Unlike the first sixteen stories, the last two sections preceding the Historical Background are collections of anecdotes and shorter vignettes. I have included them because I believe they warrant an English rendering, in that the spiritual design inherent in each adds to the overall tableau of the soul of the samurai that I have hoped to capture herein.

The four poems in this book, namely those by Takechi Hanpeita, Kondo Isami and Serizawa Kamo, and the quatrain on the Japanese sword cited at the beginning of the story titled Cutting Test, are my own translations. I have also provided an English rendering of the short jingle that Sakamoto Ryoma contrived at the expense of his enemies, and appears in the tale titled A Natural and Overwhelming Desire.

For the benefit of readers who have trouble keeping track of Japanese names, I have included a brief list of main players (in order of appearance) at the beginning of each story, and a more detailed Dramatis Personae before the first story. To remind readers which side of the revolution these samurai represented, following their names are the letters (L) [(short for Loyalist) for anti-Shogunate Imperial Loyalist], (S) [for supporter of the Shogunate] or (U) [for supporter of a union between the Imperial Court and the Shogunate]. If a characters political stance is not indicated, it does not apply to these pages. The glossary located before the index will further help readers to recall the meanings of Japanese terms.

Settings

A highway near a small village, some thirty-four miles west of Edo, August 1862

Kagoshima Bay, off of Kagoshima Castletown, capital of the Satsuma domain, at the southern extremity of the island of Kyushu, summer 1863

Players

Shimazu Hisamitsu (U) : Lord of Satsuma

Narahara Kizaemon (L) : A Satsuma samurai

To Cut a Foreigner

All of us were anxious to cut a foreigner. Suddenly there was a noise from behind, and I put my hand on the hilt of my sword. As I turned around I saw an Englishman on horseback holding his left side, galloping straight at me. I waited until he got close enough, then drew the blade, and in the same motion cut him about the left side of the body. A bloody piece of something fell on the grass. I suppose it was part of his entrails. I wanted to cut him again, so I chased after him. But since I was on foot, I couldnt catch up to him. I turned back and saw another foreigner galloping in my direction. I cut him about the right side with the same technique. I tell you, it was so awfully pleasant to cut them. I felt so very relieved. Fifty years have passed since then. When I think about it now, its like a dream.

Such were the words of a retired Japanese Army major, reminiscing of his part in the brutal slaughter of an Englishman, and the wounding of two others, in August 1862. The good major had been among a retinue of Satsuma samurai escorting Shimazu Hisamitsu, lord of the Satsuma domain, from the Shoguns capital at Edo on a twoweek trek to the Imperial capital at Kyoto. Lord Hisamitsu had been in Edo on a tour de force , accompanying two Imperial envoys who carried orders from the Imperial Court for the Shogun to report to Kyoto to discuss, among other pressing matters, expelling the barbarians from Japan and restoring peace and order to the empire.

The Shogun was Head of the House of Tokugawa, the dynasty that had ruled Japan for two and a half centuries. For fourteen generations, the Shogun had carried the official title of Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Forces Against the Barbarians. It had been conferred by the Emperor upon the founder of the Tokugawa dynasty, commonly known as the Tokugawa Bakufu, at the beginning of the seventeenth century. The Shogun had borne his illustrious title well, ruling the Japanese nation peacefully from his stronghold of Edo Castle, unopposed by the some 260 feudal lords throughout Japan, who, in turn, ruled peacefully over their individual domains. The halcyon days ended when, in 1858, the Tokugawa regime yielded to foreign pressure and authorized the first commercial treaties with foreign nations. A Shogun had not visited the Imperial Court in over two hundred years, until, pressed by the formidable Lord of Satsuma, the fourteenth Tokugawa Shogun yielded to the Imperial demand.