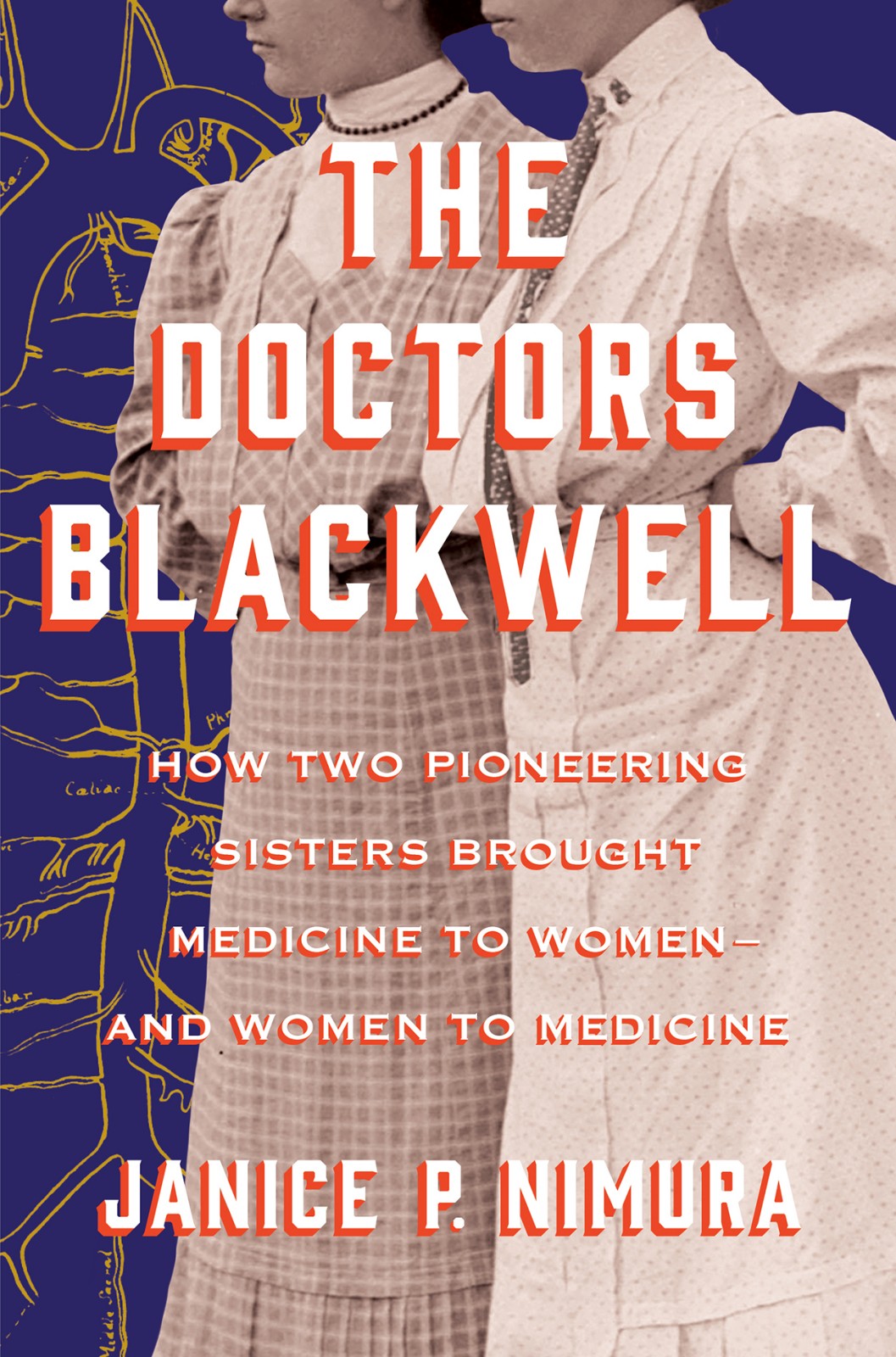

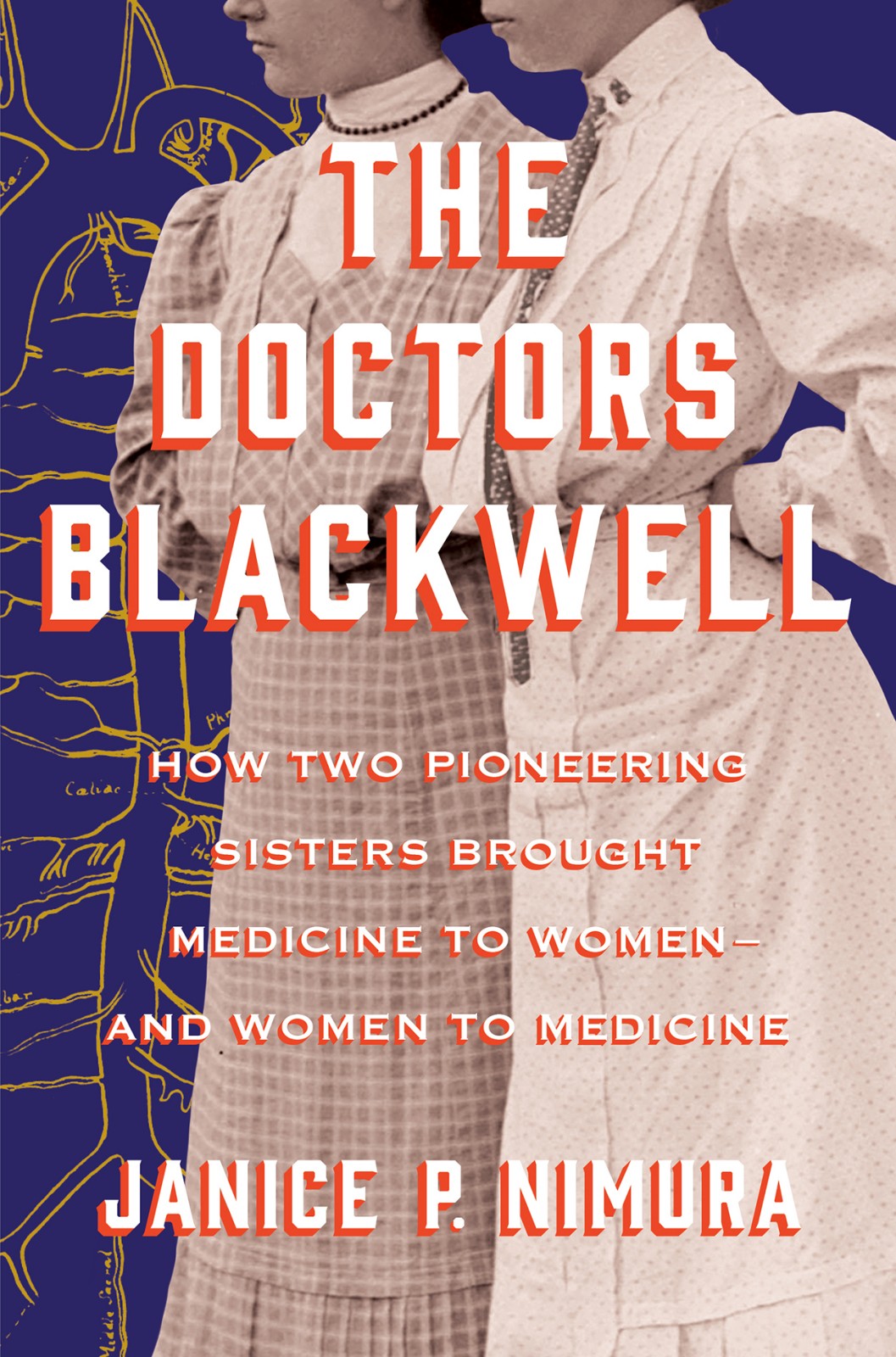

THE DOCTORS

BLACKWELL

HOW TWO PIONEERING SISTERS

BROUGHT MEDICINE TO WOMEN

AND WOMEN TO MEDICINE

JANICE P. NIMURA

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

FOR CLARE AND DAVID,

SCIENTISTS AND FEMINISTS

THE DOCTORS

BLACKWELL

O n May 14, 2018, a cheerful crowd of activist New Yorkers blocked the sidewalk at the corner of Bleecker and Crosby streets. Before them stood an elderly and unremarkable building: four stories topped by a pair of attic dormers, battered brick facade obscured by a fire escape, pre-hipster neighborhood bar on the ground floor. After a parade of speakers, all but one of them women, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation unveiled a commemorative plaque, the newest stop on its Civil Rights and Social Justice Map. In this building, it read, the first female doctor in America, Elizabeth Blackwell, established the first hospital for, staffed, and run by women.

Applause erupted, VIPs grinned, cameras clicked. There was a triumphant sense of reclaiming a hero; of restoring a story of female agency; of lifting, for just a moment, the grim political mood. Someone was selling eye-popping T-shirts, black and hot pink on white: ELIZABETH BLACKWELL: OG MD. The celebrants dispersed into the balmy evening, imagining the first female doctor: saintly and sepia-toned, bending solicitously over her grateful patients; or maybe a fiercer version, Original Gangster of medical women, crusading feminist. Both images were satisfying. Neither was accurate.

O n May 12, 1857, in a room overlooking that same corner of Bleecker and Crosby, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwellpetite, unsmiling, soberly dressedmoved into the light slanting through tall sash windows to address a small audience of ladies and a sprinkling of gentlemen. Two rows of iron bedsteads filled the space, made up with mismatched but carefully smoothed white linens. The assembled guests had settled themselves with a waggish chuckle or two about the impropriety of mixed company gathering in a room that was, strictly speaking, a ladies bedchamber. It would never be so pristine again, but for now, stethoscopes and scalpels, opium and mercury, blood and piss and all the unmentionable mess of illness and childbirth and surgery and death were nowhere to be seen.

Elizabeth cleared her throat to be heard over the hoofbeats and clatter of busy Broadway, a short block away, and read with stiff gravity from the document she held: This institution, which is publicly opened today, is a hospital and dispensary for poor women and children.

Its unprecedented purpose, she read on, was threefold: to allow women to consult doctors of their own sex, free of charge; to provide the growing number of female medical students with the practical experience denied them by established hospitals; and to train nurses. Her tone was level and businesslike, betraying no sense that for most of New Yorks burghersnot to mention their wivesthe idea of a woman doctor was outrageous. She did not mention the loneliness, drudgery, and pain she had transcended to become the first woman in America to receive a medical degree, in 1849. Nor did she acknowledge the taller, equally grave woman by her side, who shared her direct gaze and determined jawline: her sister Emily, who had struggled just as mightily to earn her own degree in 1854, and without whom this moment might not have arrived.

The trustees of the newborn New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children, thirteen men and four women, had rejected the suggestion that one of these female physicians should tell her own story that day, fearing she might sound off-puttingly like an agitator for womens rights. But Elizabeth was not a radical, however radical her choice to study medicine might seem. The full thorough education of women in medicine is a new idea, and like all other truths requires time to prove its value, she continued. Women must show to medical men, even more than to the public, their capacity to act as physicians, their earnestness as students of medicine, before the existing institutions with their great advantages of practice and complete organization will be opened to them. Then she ceded the floor to a man: Henry Ward Beecher, the heavy-lidded, silver-tongued, irrepressibly libidinous pastor of Brooklyns Plymouth Church, arguably the most famous man in New York.

There are none less able to make provision for themselves in this world than women and children, Beecher intoned, and thenwith more brio than coherenceinsisted that he believed most thoroughly in womans accomplishments. Indeed, women might well be better suited to medicine than men. Her intuition, perception and good mother wit render her so, he explained, surrendering to stereotype and dispensing with science altogether. The tread of woman in the sick chamber is itself antidote. Their expressions neutral, the Blackwell sisters applauded with the rest. Allowing this patronizing, magnetic manwhom they had known, in fact, long before his fame took holdto proclaim that woman was ordained to be a doctor was the best publicity imaginable.

A dozen years earlier, at the age of twenty-four, Elizabeth Blackwell had selected medicine as a means of proving a truth she believed to be divinely sanctioned: that women could be anything they wished according to the limits of individual talent and toil, and in reaching their fullest potential would raise humanity closer to its ideal. Medicine had not been an obvious choice for a young woman who equated illness with weakness, cared little for anyone beyond the circle of her eight siblings, and preferred the life of the mind to the functions of the bodywhich she found, quite frankly, disgusting. But God had chosen her, she believed, to pursue this arduous path, and she had chosen Emily, her most capable sister, five years younger, to follow her.

In the decades to come, Elizabeth would make greater use of her pen than her medical instruments, her opinionated eloquence preserved in reams of her own writing, both private and published. It was plainspoken, understated Emily who quietly embraced the challenge of medicine itself, Emily who would spend her life as a practicing physician, surgeon, and instructorthough like her sister, she too fell short of empathy. There is certainly nothing attractive in the care of miserable forlorn sick people, she wrote to Elizabeth. It is only as scientific illustration that I can take the least interest in them, unless it were possible to raise them, and that is a difficult matter.

Raising the expectations and ambitions of women, from the slums of Five Points to the salons of Fifth Avenue: a difficult matter indeed. Together the Blackwell sisters managed it. Their story does not fit on a plaque.

T he yellowed notebook is inscribed with perfectly straight lines of Elizabeth Blackwells careful eleven-year-old penmanship. There lived as my story says a Lady and Gentleman, it begins. The Gentleman, a manufacturer like Elizabeths father, watches his friends emigrate from England to America,

and as he knew that his business was a very good one and that he could bring up his children better there than in England he asked his wife what she thoght about going though she was was sorry to leave her native land, yet as she knew, that it was for her chidrens good she consented. [

Next page