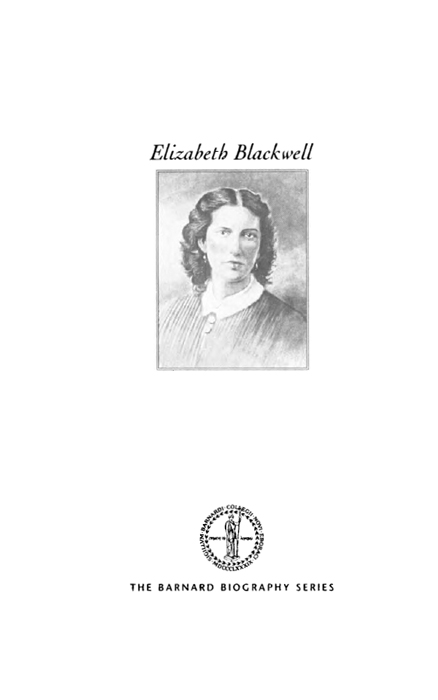

Copyright 1997 by Nancy Kline

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Conari Press, 2550 Ninth Street, Suite 101, Berkeley, CA 94710.

Conari Press books are distributed by Publishers Group West

Cover design: Suzanne Albertson

Cover portrait: Lino Saffioti

Illustration credit, page xvii: Charles Pfizer & Company

ISBN: 1-57324-057-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kline, Nancy.

Elizabeth Blackwell: a doctor's triumph / by Nancy Kline; foreword by Nancy Dubler.

p. cm. (A Barnard Biography Series; 2)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Describes the personal life and achievements of the woman credited with being the first woman physician in the United States.

ISBN 1-57324-057-5 (trade paper)

1. Blackwell, Elizabeth, 1821-1910Juvenile literature. 2. Women physiciansUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. [1. Blackwell, Elizabeth, 1821-1910. 2. Physicians. 3. WomenBiography.] I. Title. II. Series: Barnard biography series (Berkeley, Calif.); 2.

R154.B623K576 1997

610'3.92dc20

[B]

96-42011

CIP

AC

Printed in the United States of America on recycled paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

For

Adam

and

Ana

Acknowledgments

A number of people have given this biography attentive readings and have offered invaluable suggestions as to how it might be strengthened. I want to thank them all. Among my earliest and most helpful audiences were the XIs, XIIs, and XIIIs of City & Country School and their teacher Ellen Wertzel, as well as the members of the Women Writing Women's Lives Seminar. Both Theresa Rogers and Nancy Woloch of Barnard College read the book with an expert eye and made detailed and insightful comments on the manuscript that were crucial to its revision.

I am grateful to Sandra and Kelly Turner for their enthusiasm, support, and patience in the early stages of the project; to Dr. Ann Yee and Dr. Morris Podolsky for their technical expertise; and to the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and The MacDowell Colony for providing me with the space and silence in which to finish my work.

Special thanks are due Catherine Gourley, my exemplary editor at Conari Press, for the scrupulous attention with which she read and helped to shape the manuscript, and for her grace and humor in dealing with its author.

To Beverly Solochek, who championed the book from the very start, I offer my deepest gratitude. She is a splendid colleague and a dear friend.

Contents

Foreword

T wenty years ago, when my daughter was four, her post nursery school treats included watching Sesame Street. In one particular episode, the Cookie Monster was visited by a doctora womanwho prescribed medicine for his fever. My daughter seemed puzzled. Men were doctors, she explained confidently, and women were nurses. She delivered this review of gender divisions in the healing professions despite the fact that she was regularly cared for by a woman pediatrician, her teeth examined by a woman dentist, and her eyes tested by a woman ophthalmologist. Six months before, when her brother had mashed her finger in the hinge of the door, she had been sutured by a woman surgeon. Despite personal history, however, her observations reflected both the power of popular imagery and how slowly masculine professional hegemony in medicine had receded.

Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor in America, had begun the process of professional reform in 1847, when she was admitted to the Geneva Medical College of Western Medicine on a fluke. For Elizabeth, entrance into medical school was the result of years of dogged persistence in pursuit of her dream to become a doctor.

The reasons for the exclusion of women from the professions were many. Acceptable eighteenth century notions of middle-class womanhood began and ended with domesticity. Lower-class women and girls regularly worked at bone-crunching jobs, acting as donkeys and pulling carts in the coal mines or toiling in the factories for long days and a few pennies' wages, but middle-class women were restricted to work in the home, cultivating delicate sensibilities and house-womanly skills and virtues. Victorian sensibilities, values, and laws precluded women's independence and suffrage, most inheritance, and all professional learning and opportunity.

Victorian prudishness also recoiled at the notion of a woman learning about or touching a body. Medicine was about bodies, and bodies were shameful aspects of the human condition to be denied and hidden away. Discussions about body functions, illness, disease, and sexuality were not proper in any polite company that included women.

Not only did the biases of society differ from our own, but the practice of medicine would be unrecognizable to a contemporary physician. In Elizabeth Blackwell's time, medicine would occasionally diagnose, sometimes give comfort, but almost never cure. Surgery was done without anesthesia, and many patients preferred certain death to the horror of the surgical knife. Antisepsis was unknown and physicians went from one patient to another spreading the very diseases they sought to combat. The discovery of antibiotics was still a century away, and the development of machines to support breathing, heart rhythms, and kidney function were not even within the purview of futuristic speculation.

What medicine was, however, was a large and fairly well-organized men's club that offered some prestige andfor at least some doctorssubstantial financial reward. There was no state licensing of physicians and anyone who chose to could post a sign and begin practice. Some had skill and education; others had little more than callous disregard for the welfare of the patient.

The worst care was probably that given to women. Victorian prudishness banned male physicians from looking at their female patients if they were examining them for vaginal or uterine illness or for breast cancer. A broken ankle might be carefully examined but little else was. Women escaped total butchery because childbirth was largely handled by women midwives whose formal education, folk wisdom, and empathy prepared themsomewhatto assist during childbirth with at least a small modicum of competence. But this, too, was under attack as physicians, seeing midwives as competitors, tried to have laws passed that would prohibit non-physicians from supervising childbirth.

In Elizabeth Blackwell's time, various states first began to pass statutes that made abortion a crime. For some men, who were then the sole occupants of state legislatures, these statutes reflected religious dictate and moral obligation; for others, they were the means to limit women's decision-making ability over family size and to restrict the place of women in medicine. As midwifery was strangled, it left the care of women in the hands of men.

In Elizabeth Blackwell's time, a woman's individual choices about careers, about the size and timing of a family, and about how women can control their own bodies were denied. Rather than accepting the way things were, Elizabeth Blackwell responded to this powerlessness. Determined to change the complex economic, social, and moral universe that was her world, Elizabeth Blackwell provided women with skilled and sensitive care so that they would not choose death over the horrible prospect of being touched or examined by a strange man.

Next page