Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

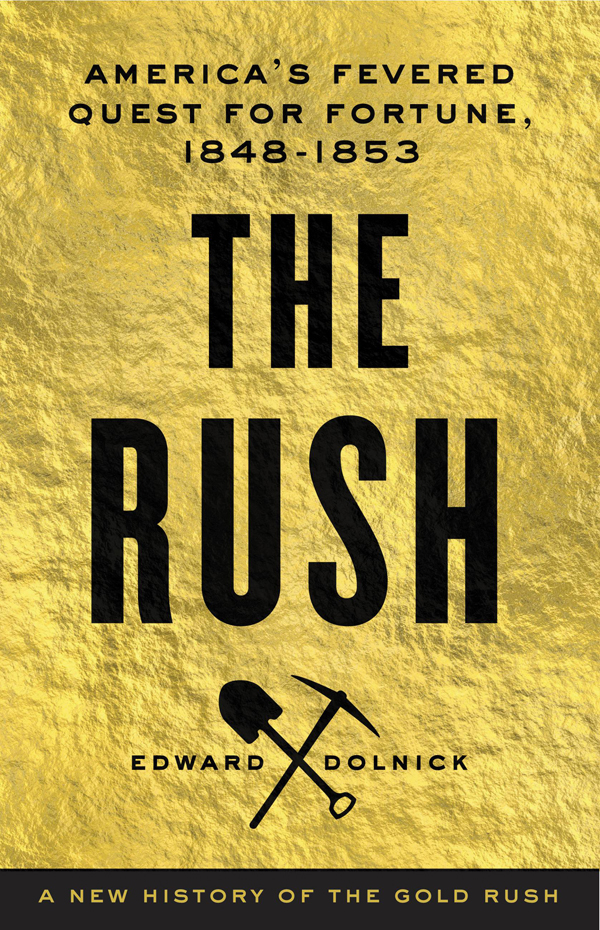

Copyright 2014 by Edward Dolnick

Cover design by Ben Wiseman; cover texture Dimec / Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2014 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Author photography by Lynn Golden

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: August 2014

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The author is grateful for permission to reprint illustrations as follows:

, Henry W. Bigler Diary, Jan. 24, 1848. The Society of California Pioneers.

, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

, Rufus Porter, Aerial Navigation (New York: H. Smith, 1849).

, Le Petit Journal, Dec. 1, 1912.

, Joseph Goldsborough Bruff, Diaries, Journals, and Notebooks, Western Americana Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

by the author.

ISBN 978-0-316-28055-6

E3

The Clockwork Universe

The Forgers Spell

The Rescue Artist

Down the Great Unknown

Madness on the Couch

To Lynn

The planter, the farmer, the mechanic, and the laborer all know that their success depends upon their own industry and economy, and that they must not expect to become suddenly rich by the fruits of their toil.

President Andrew Jackson, 1837

A frenzy seized my soul; piles of gold rose up before me at every step; castles of marble; slaves bowing to my beck and call; virgins contending with each other for my love in short, I had a very violent attack of the Gold Fever.

James Carson, a soldier stationed in California, 1848

A BANDONED BY HIS COMPANIONS, starving, and trapped by snowstorms high in the Sierra Nevada, even a pathologically optimistic man like J. Goldsborough Bruff found himself fretting. He had thought he could outlast the cold and snow until a rescue party turned up, but months had passed. Now he could scarcely muster the strength to stumble in search of food.

Dinner one night had consisted of candles melted in a skillet, and, another night, boiled woodpecker. A few days later, Bruff found a half-decayed deers skull; the worms and bugs had left a bit of meat, and Bruff shared it with his faithful dog, a bull terrier named Nevada. (The scraps, Bruff conceded in his diary, would have been, probably, in different circumstances, quite disgusting!) That was breakfast on April 1, 1850. It marked a step up from another recent meal, coffee grounds with salt. To keep his spirits up, Bruff recited over and over, I will soon have plenty to eat! Bread and meat, coffee and milk! A house to sleep in! An end of my sufferings!

Back at home, he had entertained more extravagant fantasies. Bruff was an architectural draftsman from Washington, D.C., with a wife, a houseful of children, a secure job, and a thirst for adventure. In 1849, no one in the East could talk of anything but the gold strike in California. For weeks, Bruff listened and pondered and sat awake late at night studying guidebooks. Finally, his mind made up, he shoved his sharpened pencils aside. Soon he had organized a company of sixty-six men and seventeen mule-drawn wagons. The party sported dashing uniforms, new weapons, and a suitably imposing name.

On April 2, 1849, with Bruff at their head, the Washington City and California Mining Association marched to the White House to meet the president. Then they headed for California and a life of ease and luxury.

Almost exactly a year later, Bruff gathered his strength for a final attempt at escaping the mountains. Staggering his way, falling to the ground every few steps, he inched along. He ate the last of his candles. He gave the wick to Nevada.

I N AMERICA IN THE mid-1800s, everyone knew that two laws governed the world. First, the path to success was long and difficult; the race was not to the swift but to the diligent, who collected their pennies day after day. Second, calamity came in countless guises and swooped down without warning. Jobs, savings, and homes could vanish overnight. In the Panic of 1837, a forerunner of the Great Depression, meat doubled in price; so did flour. Nearly half the banks in the country failed. President Martin Van Buren, who rejected any efforts by the government to ease the crisis as effeminate indulgence, came to be known as Martin Van Ruin. In eastern cities, one man in three was unemployed, and crowds of rioters shouted, Bread! Bread! Bread! Tens of thousands of hungry, homeless New Yorkers wandered the citys streets.

Private disasters struck as broadly and haphazardly as public ones. In an age with no understanding of germs or bacteria or infection, disease ran unchecked. Doctors had little to offer their patients but kind words and dubious potions. Mothers and fathers watched helplessly as scarlet fever or whooping cough or measles picked off one of their children, and then another, and then another. Parents who had not seen a child die were unusually fortunate.

Amputations and other operations were ordeals that looked like scenes from Edgar Allan Poe. Surgeons operated in blood-soaked frock coats and, in the interest of speed, held their knives in their teeth as they switched between cutting and sawing. Every family had seen mishaps turn into calamities. In 1842 Henry Thoreaus brother nicked himself while shaving; in a week lockjaw set in, and spasms and convulsions racked his body; in another three days he was dead. The powerful and prominent were as vulnerable as everyone else. William Henry Harrison, elected president in 1840, delivered a two-hour-long inaugural address on a cold, rainy day, without a coat. He caught pneumonia. The best doctors in the land bled him and blistered him and plied him with castor oil, opium, wine, and brandy. To no avail. Harrison died a month after taking office.