For my mentor and friend, Kurt Fischer

In all affairs its a healthy thing now and then

to hang a question mark on the things

you have long taken for granted.

BERTRAND RUSSELL, BRITISH PHILOSOPHER

CONTENTS

Guide

I n the late 1940s, the United States Air Force had a serious problem: its pilots could not keep control of their planes. Although this was the dawn of jet-powered aviation and the planes were faster and more complicated to fly, the problems were so frequent and involved so many different aircraft that the Air Force had an alarming, life-or-death mystery on its hands. It was a difficult time to be flying, one retired airman told me. You never knew if you were going to end up in the dirt. At its worst point, seventeen pilots crashed in a single day.

The two government designations for these noncombat mishaps were incidents and accidents, and they ranged from unintended dives and bungled landings to aircraft-obliterating fatalities. At first, the military brass pinned the blame on the men in the cockpits, citing pilot error as the most common reason in crash reports. This judgment certainly seemed reasonable, since the planes themselves seldom malfunctioned. Engineers confirmed this time and again, testing the mechanics and electronics of the planes and finding no defects. Pilots, too, were baffled. The only thing they knew for sure was that their piloting skills were not the cause of the problem. If it wasnt human or mechanical error, what was it?

After multiple inquiries ended with no answers, officials turned their attention to the design of the cockpit itself. Back in 1926, when the army was designing its first-ever cockpit, engineers had measured the physical dimensions of hundreds of male pilots (the possibility of female pilots was never a serious consideration), and used this data to standardize the dimensions of the cockpit. For the next three decades, the size and shape of the seat, the distance to the pedals and stick, the height of the windshield, even the shape of the flight helmets were all built to conform to the average dimensions of a 1926 pilot.

Now military engineers began to wonder if the pilots had gotten bigger since 1926. To obtain an updated assessment of pilot dimensions, the Air Force authorized the largest study of pilots that had ever been undertaken. In 1950, researchers at Wright Air Force Base in Ohio measured more than 4,000 pilots on 140 dimensions of size, including thumb length, crotch height, and the distance from a pilots eye to his ear, and then calculated the average for each of these dimensions. Everyone believed this improved calculation of the average pilot would lead to a better fitting cockpit and reduce the number of crashesor almost everyone. One newly hired twenty-three-year-old scientist had doubts.

Lieutenant Gilbert S. Daniels was not the kind of person you would normally associate with the testosterone-drenched culture of aerial combat. He was slender and wore glasses. He liked flowers and landscaping and in high school was president of the Botanical Garden Club. When he joined the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Air Force Base straight out of college, he had never even been in a plane before. But it didnt matter. As a junior researcher, his job was to measure pilots limbs with a tape measure.

It was not the first time Daniels had measured the human body. The Aero Medical Laboratory hired Daniels because he had majored in physical anthropology, a field that specialized in the anatomy of humans, as an undergraduate at Harvard. During the first half of the twentieth century, this field focused heavily on trying to classify the personalities of groups of people according to their average body shapesa practice known as typing.

Daniels was not interested in typing, however. Instead, his undergraduate thesis consisted of a rather plodding comparison of the shape of 250 male Harvard students hands.

So when the Air Force put him to work measuring pilots, Daniels harbored a private conviction about averages that rejected almost a century of military design philosophy. As he sat in the Aero Medical Laboratory measuring hands, legs, waists, and foreheads, he kept asking himself the same question in his head: How many pilots really were average?

He decided to find out. Using the size data he had gathered from 4,063 pilots, Daniels calculated the average of the ten physical dimensions believed to be most relevant for design, including height, chest circumference, and sleeve length. These formed the dimensions of the average pilot, which Daniels generously defined as someone whose measurements were within the middle 30 percent of the range of values for each dimension. So, for example, even though the precise average height from the data was five foot nine, he defined the height of the average pilot as ranging from five seven to five eleven. Next, Daniels compared each individual pilot, one by one, to the average pilot.

Before he crunched his numbers, the consensus among his fellow air force researchers was that the vast majority of pilots would be within the average range on most dimensions. After all, these pilots had already been preselected because they appeared to be average sized. (If you were, say, six foot seven, you would never have been recruited in the first place.) The scientists also expected that a sizable number of pilots would be within the average range on all ten dimensions. But even Daniels was stunned when he tabulated the actual number.

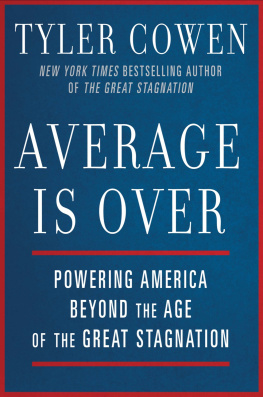

Zero.

Out of 4,063 pilots, not a single airman fit within the average range on all ten dimensions. One pilot might have a longer-than-average arm length, but a shorter-than-average leg length. Another pilot might have a big chest but small hips. Even more astonishing, Daniels discovered that if you picked out just three of the ten dimensions of sizesay, neck circumference, thigh circumference, and wrist circumferenceless than 3.5 percent of pilots would be average sized on all three dimensions. Danielss findings were clear and incontrovertible. There was no such thing as an average pilot. If youve designed a cockpit to fit the average pilot, youve actually designed it to fit no one.

Danielss revelation was the kind of big idea that could have ended one era of basic assumptions about individuality and launched a new one. But even the biggest of ideas requires the correct interpretation. We like to believe that facts speak for themselves, but they most assuredly do not. After all, Gilbert Daniels was not the first person to discover there was no such thing as an average person.

A MISGUIDED IDEAL

Seven years earlier, the Cleveland Plain Dealer announced on its front page a contest cosponsored with the Cleveland Health Museum and in association with the Academy of Medicine of Cleveland, the School of Medicine, and the Cleveland Board of Education. Winners of the contest would get $100, $50, and $25 war bonds, and ten additional lucky women would get $10 worth of war stamps. The contest? To submit body dimensions that most closely matched the typical woman, Norma, as represented by a statue on display at the Cleveland Health Museum.

Norma was the creation of a well-known gynecologist, Dr. Robert L. Dickinson, and his collaborator Abram Belskie, who sculpted the figure based on size data collected from fifteen thousand young adult women. Like many scientists of his day, Dickinson believed the truth of something could be determined by collecting and averaging a massive amount of data. Norma represented such a truth. For Dickinson, the thousands of data points he had averaged revealed insight into a typical womans physiquesomeone normal.