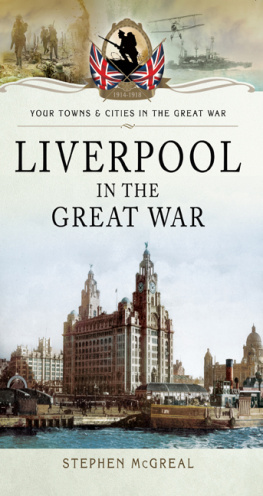

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by

PEN & SWORD MARITIME

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Stephen McGreal, 2008

ISBN 978 1 84415 858 4

ISBN 978 1 84468 249 2(ebook)

The right of Stephen McGreal as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by Biddles Ltd.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

This book is dedicated to the memory of Claire Louise McGreal

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave

Who biddest the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!

William Whiting 1860

Contents

Appendices:

During the early seventies while working as an apprentice shipwright within Cammell Laird Shipbuilders and Engineers I first became aware of men who, while serving in the merchant navy, survived an attack by torpedo. In this instance an unlikely-looking veteran of the Second World War had sailed as a carpenter on merchant ships running the gauntlet of the U-boat packs. In my youthful innocence the man appeared rather old, forgetful and occasionally confused. His workmates explained his demeanour in whispered tones His ship was torpedoed while he was securing cargo in the hold. He managed to scale the hold escape ladders with the sea water lapping at his heels and never quite recovered from the experience. He was evidently suffering from what we now term Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, something I would again become acquainted with during a stint as a carpenter in the merchant navy.

In the 1970s ageing veterans of the Second World War Atlantic convoys still abounded in an ever shrinking British-staffed merchant navy; they, like so many former veterans, shied away from discussing their wartime experiences. However, one individual routinely kept his cabin light off during the night, so as not to show a light to submarines! During the war his tanker was torpedoed off the Caribbean island of Curaao, and whenever our tramp tanker approached the island he suffered flashbacks, packed a valise and prepared to go to hospital. Three decades later the consequences of the term ship torpedoed took on a new meaning as I witnessed at first hand, the trauma revisit an ageing seaman. It is a sobering thought indeed to imagine the fear and anxiety experienced by the merchant navy personnel as they determinedly maintained the United Kingdoms essential food and materials lifeline. The fourth service depended on women and men like my maternal great-grandfather who survived a torpedo attack off the Irish coast; family legend maintains he returned home, still in his wet clothes. To add insult to injury when a vessel sank, the shipping companies automatically ceased paying wages to the crew. Denied an income, the seafarer generally signed on the next outward bound ship; faced with the starvation of their families most took to the sea, to worry about the U-boats another day. During the great recruitment drive for the army, volunteers officially had to be aged between eighteen and forty-one years old, extended upwards in 1918 to fifty-one. The Mercantile Marine had no such confines, exemplified by Mrs Bridget Trenerry, a sixty-five-year-old stewardess drowned on Asturias. If a persons past life flashes by in the seconds before death, seventeen-year-old Henry George Taylors must have passed in the blink of an eye, as he drowned trapped in the bowels of the Dover Castle. Their status as non-combatants meant little during the merciless war at sea.

As a keen amateur military historian, occasionally my research into a Great War combatant abruptly halted, with the sinking of what I imagined to be a troopship or leave boat. Occasionally further research revealed the torpedoed or mined vessel was actually a hospital ship. It seemed perverse that any belligerent should torpedo a vessel fulfilling a humanitarian role, yet history records numerous deliberate instances. Perhaps after the wars everyone decided to let sleeping dogs lie, for although the First World War press used the hospital ship losses as a powerful anti-Germanic propaganda weapon, evocative books on this still controversial subject are scarce. Internet forums abound with questions and answers appertaining to the demise of this or that hospital ship. Despite the immunity of the Geneva Red Cross the hospital ships became fair game, in a theatre of war largely overlooked by people whose modern perception of the First World War is one of trench warfare.

Intrigued by this relatively unrecognised aspect of the First World War and remembering my experiences with torpedoed veterans, I pondered on how much worse the situation may have been for those incapacitated on a rapidly sinking hospital ship. While searching for first hand survivor accounts within archives my enquiries revealed a startlingly overlooked chapter of maritime history fought by belligerents with an intensity to equal the war of attrition waged on the Western Front. In the post-armistice years the vessels of the Mercantile Marine resumed their usual service, past glories eventually faded into obscurity, as did the crews who faded away. This work attempts to again bring to the fore the terrible price paid by the heroic men and women of the Mercantile Marine and medical services who served on the Commonwealth hospital ships.

Throughout the compilation of this book my working day has been enlightened by the occasional arrival of information, or photographs of individuals and vessels connected with the war on the hospital ships. With the assistance of the following people this project has greatly benefited from the assorted images sent by email or snail mail to my overflowing desk, and for this I would like to thank the following. Rather than list the contributors in any specific order I have elected to list the names alphabetically.

Stanley Amos for shipping images. Bryan Bidwell, for information relating to Private E Bamford. Pat Cartmell for the Dover Castle survivors image. Mike Carty for images. Jennifer Marrack Cohen, for the photograph of Alice May Swaffield Milward VAD. Jonathan Collins. George Donnison. Pamela Eustice of Southern Australia, for the image and details of Robert Sharp. Angela Hamilton. Barbara Head of the Trinity House Corporation. P Jones for the copy of With a camera in my pocket. Stephanie Levitt for a photograph of the Hollybrook Memorial. Mair and Dennis Miller for the images of Private Huws and Warilda. Gina Parsons. Paul Robinson. Joyce Stevenson, for her Warilda information and the image of Walter Long. Myra Thomas. Peter Threlfall for various images. Mike Whiteford, for the photograph of Private W A Boggis.

Next page