It would not have been possible to complete a project such as this, which draws on archive material distributed all around the world, without assistance from many correspondents, colleagues and enthusiasts, and I would like here to acknowledge those persons and organisations for their valued contributions. It is thanks to their generosity with photographs that would otherwise have been difficult to locate, and the benefit of their specialised and detailed knowledge of the careers of some of the less well-known ships, that this extensive account of the wartime mercy ships has been made possible.

Accordingly, I would like to put on record my warmest appreciation of the help I received from: Jean-Yves Brouard, Michael Cassar, Nereo Castelli, Luis Miguel Correia, Mario Cicogna, Lars Hemingstam, Richard de Kerbrech, Anibal Jos Maffeo, Carlos Mey, Peter Newall, the late Luca Ruffato, and Paolo Valenti.

Besides those individuals, a number of institutions have graciously supported my efforts, among them the following, with recognition of their members of staff who assisted me: British Path (Ruth Cahir), British Red Cross HQ, London (Jane High), Bndesarchiv (Martina Caspers), Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum (Klaus Fuest), East Asiatic Co. (Erik Ljunggren), Guildhall Library, Histarmar, Museu Maritim di Barcelona (Javier Aznar), National Archives, News UK Group Publishing Services (Nick Mays), NYK Maritime Museum (Hakuei Wakiya), International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva (Daniel Palmieri and his staff), Sjfartsmuseet Akvariet (Cilla Ingvarsson), Swedish Red Cross (Sonja Sjstrand), United States National Archives & Records Administration (Kim McKeithan), World Ship Society (Jim McFaul and Tony Smith) and WZ-Bilddienst Bildarchiv (Sibylle Jaspers).

Last but not least, I would like to express my thanks to Amy Rigg of The History Press for her invaluable support and guidance.

CONTENTS

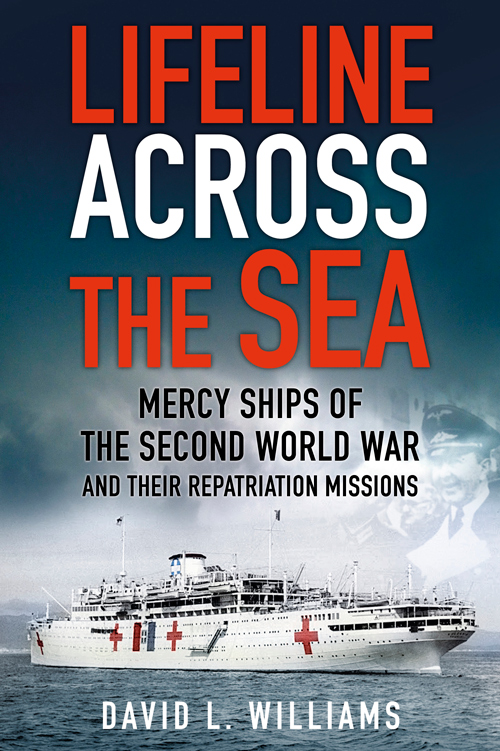

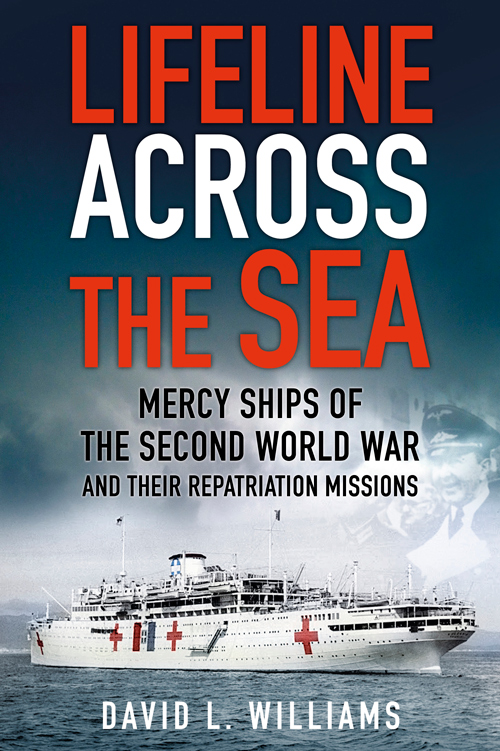

Behind the scenes during the Second World War, a series of agreements were concluded through negotiations between the combatants whereby prisoners, usually wounded or gravely ill, protected personnel doctors, nurses, stretcher bearers, ambulance crews and other medical personnel, as well as chaplains and diplomats, civilians and alien internees could be safely exchanged. It is a dimension of the war at sea about which, with few exceptions, little is widely known. Working through neutral intermediaries and conducted under the auspices of the International Red Cross, deals were reached individually between the United Kingdom and each of the Axis belligerents, Germany, Italy and Japan. Likewise, such exchanges were also arranged with the Axis by the United States and other Allied nations.

Some thirty or so repatriation missions, derived primarily from the rules of the Geneva Convention, took place during the war, while more than fifty ships, both Allied and Axis, defined as specific types of Safe-passage vessels by the Hague Convention and other maritime law, were engaged in the highly dangerous work of sailing undefended and invariably alone through hostile waters to deliver their precious human cargoes. Mainly former passenger liners, they were supported by short-sea vessels and train ferries as well as some cargo ships, many of them adorned in unique livery. At night, they were required to be brightly illuminated, making them strangely conspicuous when most ships were seeking concealment. The ships were constantly at risk of erroneous attack by submarine or aircraft, their safety and security depending totally on the transmission and receipt of unambiguous commands to the armed units in their paths stipulating that they should be allowed to proceed unharmed. The vagaries of war circumstances, the possibility of misidentification in inclement weather and the still relatively primitive nature of radio equipment at that time, prone to interference and restricted in its use to prevent detection, all combined together to magnify the hazards. The prospect of attack and severe loss of life were a constant cause of anxiety for those involved in these operations.

To set the scene, in order to appreciate the complexities and potential issues that surrounded these humanitarian efforts, some of the legal and organisational framework requires explanation the nature and work of the facilitating institutions, the types of protected ship and the criteria and mechanisms whereby persons qualifying for exchange were selected.

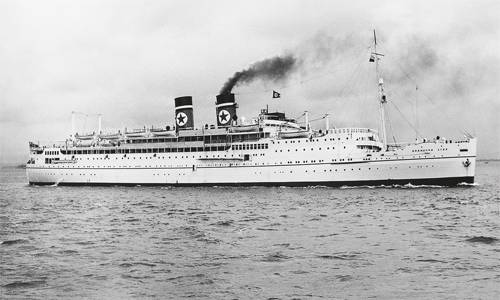

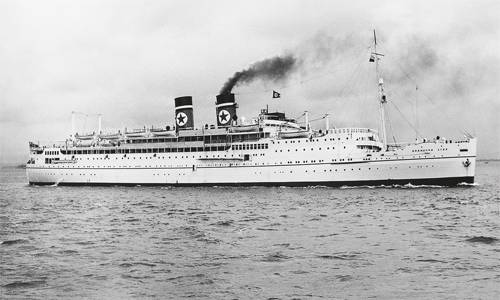

Those endangered persons from whom potential repatriates could be drawn were both numerous and various in character. Warfare, no matter what its intensity or duration, can throw up thousands, even millions, of displaced persons of a variety of descriptions. In the Second World War, within all the belligerent countries, there were countless numbers of those who were either directly affected by the conflict or who became victims of security clampdowns on the outbreak of hostilities. Quite apart from refugees seeking shelter from the violence, there were many other civilian categories at threat, either trapped or incarcerated. Among them were enemy aliens, ex-patriot and domiciled foreigners who previously had been accepted by a domestic population but who, at the onset of hostilities, were rounded-up and interned. In Britain around 80,000 aliens were identified who potentially presented a security risk. The vast majority were interned in camps on the Isle of Man. Over 7,000 were subsequently deported to Australia and Canada, a risky business as substantiated by several high-profile losses to U-boat attack, among them the Arandora Star with 805 casualties, the majority Italians, and the Empress of Canada from which another 392 were killed.

The Arandora Star was sunk west of the Bloody Foreland on 2 July 1940 while bound from Liverpool to Canada with Italian and German internees. Lacking safe-conduct protection, she was a legitimate target for U-47. Maritime Photo Library

In the case of the Empress of Canada , sunk on 14 March 1943, she was loaded with both refugees and Italian prisoners, many of whom perished. Authors collection

In Germany, millions of Jewish civilians were sent to concentration camps along with the political opponents of the Nazis and members of minority religious orders. When war broke out in the Far East, the American Government implemented a major programme of arrest and internment of 100,000 Japanese-Americans, often in poor conditions, and between 1941 and 1942 more than 130,000 civilians of British, American, Dutch and Commonwealth origin who were living and working in invaded territories were incarcerated by the Japanese. Last, but not least, arising from the normal process of exchange of embassy and consular staff, there were the diplomats located in foreign embassies and consulates, along with their families. Often the last to leave because their essential services were required to the end, they were frequently and unavoidably left stranded within enemy borders when diplomatic relations were severed or war was declared.

Next page