About the Author

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita is Julius Silver Professor of Politics at New York University and a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. A specialist in policy forecasting, political economy and international security policy, he received his doctorate in political science from the University of Michigan. Bueno de Mesquita is the author of fourteen books and numerous articles for journals, newspapers and magazines. He is a partner in a consulting firm focused on government and business applications of his game theory models. He lives in San Francisco and New York City.

About the Book

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita can predict the future.

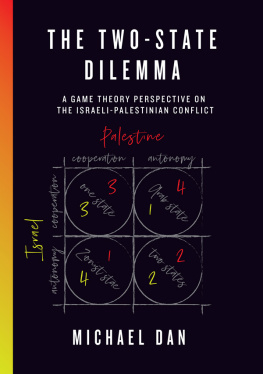

From international terrorism to corporate fraud, from climate change to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita has been predicting the future for decades. Using Game Theory (a theory based on the rationale that everyone acts in their own self-interest) he can foretell and even engineer events. His forecasts, for everyone from the CIA to major international companies, have an extraordinary 90% success rate. In this fascinating and immensely readable book he explains how you can use Game Theory to your own advantage to win a legal dispute, advance your career and even get the best possible price for your car. Prediction will change your understanding of the world both now and in the future.

Mesquita offers zingily provocative ideas Guardian

Fruitful reading that will make it difficult to look at the world through quite the same eyes as in ones virginal, pre-game theory days Kirkus Reviews

This ebook is sold subject to the conditin that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form (including any digital form) other than this in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Epub ISBN: 9781446444368

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Vintage 2010

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Copyright Bruce Bueno de Mesquita 2009

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita has asserted his right under the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

The Bodley Head

Vintage

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

www.vintage-books.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099531845

www.vintage-books.co.uk

For my grandchildren,

Nathan, Clara, Abraham, Hannah,

and those who may be yet to come.

They will be fine caretakers

of the future.

Contents

Introduction

1. What Will It Take to Put You in This Car Today?

2. Game Theory 101

3. Game Theory 102

4. Bombs Away

5. Napkins for Peace: Defining the Question

6. Engineering the Future

7. Fast-Forward the Present

8. How to Predict the Unpredictable

9. Fun with the Past

10. Dare to Be Embarrassed!

11. The Big Sweep: The History of Worms, or Bali High, Bali Low

Epilogue

Appendix

Acknowledgements

Appendices

Notes

Introduction

KING LEOPOLD II, remembered today as Belgiums Builder King, reigned from 1865 to 1909.1 A constitutional monarch who, like many of his contemporaries, longed for the bygone days of absolute power, he was nonetheless an unusually influential and activist king who helped make Belgians free, prosperous, and secure.

Belgiums good works during Leopolds reign are almost uncountable. He oversaw the expansion of political freedom with the adoption of universal adult male suffrage in competitive elections, putting his country on a firm footing to become a modern democracy. On the economic front, he encouraged free-trade policies that guided Belgium to remarkable growth. In little Belgium, coal production, the engine of industry in nineteenth-century Europe, rose to such heights that it almost equaled that of France. Social policy too moved briskly ahead. Primary education became compulsory, and with the 1881 School Law, girls were assured access to secondary education.2 Moreover, Leopolds policies provided greater protection for women and children than was then the norm in most of Europe. Thanks to legislation passed in 1889, children under twelve could not be put to work, and after they turned twelve their workdays were limited to twelve hours, a radical departure from prevailing policy of the time.

When the Belgian economy was racked by a major economic crisis in 1873, Leopold helped improve the lot of the poor with pro-labor reforms, including granting workers the right to strike, a right that was still hotly resisted in the United States half a century later. He promoted truly ambitious public works projects, including massive road and railway construction designed to reduce unemployment, promote urbanization, and increase business opportunities. He was way ahead of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Barack Obama in recognizing how to stimulate employment and economic prosperity by building up infrastructure.

Leopold was a great reformer at home, a founder of Belgiums long years of peace and plenty.

But then there was the Congo.

Though he never set foot in Africa, Leopold also ruled over the Congo Free State for nearly a quarter of a century (18851908). He built his personal wealth in the Congo first by extracting high-priced ivory from the region and then by exploiting the even more lucrative rubber trade that developed there. Unlike in Belgium, there was no chef de cabinet (roughly, prime minister), and no voters among the Congos approximately 30 million people to limit what he could do. Because it was his personal property, Leopold was free to exert the absolute rule he could not have at home. His police, the Force Publique, became the key to governing the Congo. Their job was to extract wealth for him (and for themselves) by ensuring the vast exportation of rubber to meet world demand. This band of butchers was led by a small number of Europeans who kidnapped and enslaved Congolese as soldiers who were in turn responsible for making sure that rubber quotas were met. Slave labor was the Force Publiques preferred mode of production, so its soldiers set about enslaving Congolese men, women, and children.

Leopolds police received low salaries but could earn big commissions by meeting or exceeding their rubber quotas. Unrestricted by any law governing their conduct except, literally, the law of the jungle, and provided with a huge financial incentive through the commission system, these soldiers of sorrow, from the very bottom of the ladder to the very top, used whatever means they saw fit to meet the quotas. The incentives included not only riches for those who succeeded but the severest punishment for those who failed, including beatings and even death. To avoid this fate the police tortured, maimed, and often murdered those below them who threatened (or could be claimed to have threatened) rubber production. Rewarded for killing people allegedly engaged in antigovernment activities and needing to account for every bullet they spent, soldiers quickly took to indiscriminate mutilation of innocent souls as a way to boost their counts and thereby their fees, going so far as to chop off the right hands of women and children to provide evidence of their work on behalf of Leopolds interests. Perhaps as many as 10 million people were murdered at the hands of the Force Publique in their pursuit of wealth for Leopold and, of course, for themselves.3

Next page