Published by Little, Brown

ISBN: 978-1-4055-1973-1

Copyright 2014 John Kampfner

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Little, Brown

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

To my parents Betty and Fred

Contents

PART ONE

Then

PART TWO

Now

No man is rich enough to buy back his past.

Oscar Wilde

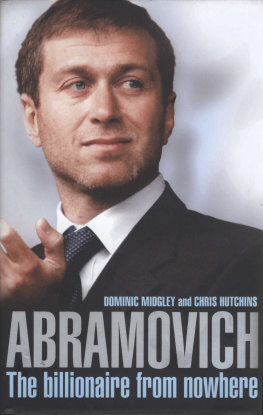

This wasnt any old lobster. It was super-sized, a giant crustacean struggling to fit onto my bone-china plate. Opposite me the wife of a British diplomat smiled nervously, sharing my anxiety about how to tackle this dead monster. This was 1992, my first social engagement with a Russian oligarch. Vladimir Gusinsky and his wife Lena had invited a small group for dinner to their Moscow apartment, just down the road from the citys largest sculpture of Lenin at October Square. The waiters in their bowties hovered around us with excessive courtesy, constantly refilling our glasses with Chablis premier cru.

Russia was changing before my eyes. A tiny slew were getting rich beyond their wildest dreams. Only a year or two earlier, the roles were reversed. Although the best I would offer guests was a can of Heineken, from a foreigners-only hard-currency shop, I knew that as part of a small band of comfortable Western expats I was the object of envy. By the middle of that decade, by now back in London, I watched the gradual invasion of the first generation of New Russians. Some of those same friends of mine would pick disdainfully at their food at Gordon Ramsay, leaving most of it on their plate for show. Or they would drop into conversation about their most recent long weekend in Cap Ferrat.

Thus began my personal fascination with the global super-rich, their lifestyles, but more their psychology. First things first: we should admit that we are obsessed with the super-rich. We envy and abhor their lifestyles. We say we loathe what they have done to society, but we love to read about them in glossy magazines and to chart their success on lists.

How have these people achieved their success if success is the right term for the sudden appropriation of wealth? Why are they so blessed? Are they smarter, more determined or just luckier than the rest of us? Is the present crop of wealthy any different from those who have come before? The people who are blamed for the economic crisis and for widening inequality are still living in their parallel worlds, raking in the bonuses, taking their private jets to their private islands, while doling out the odd scrap known as philanthropy. We think in the second decade of the third millennium AD that we are living through a uniquely divisive and unequal era. But are we? I decided to investigate, to delve into the past two thousand years in fact in search of answers.

Starting with ancient Rome, moving on to the Norman Con quest, the Malian kingdom, the Florentine bankers and the great European commodity traders, this story culminates with the oligarchies of modern Russia and China and the elites of Silicon Valley and Wall Street. From ancient times to the present day, from periods of stability to those of hubris and decline, they have more in common than we realise. For every Roman Abramovich, Bill Gates and Sheikh Moham med there is an Alfred Krupp and Andrew Carnegie. The twenty-first-century super-rich are not an oddity of history. They can thank their predecessors for teaching them the lessons.

How do people become rich? They do so by fair means and foul, by entrepreneurship, appropriation and inheritance. They make markets and they manipulate them. They defeat the competition or they eliminate it. They gain or buy influence among the political leadership and the cultural and social elites. For more than a century American politics has made no secret of the link; indeed, it celebrates it. The more lavish the fundraiser, the more politicians feel obliged to attend. One such example is the Alfred E. Smith memorial dinner, a white-tie affair at New Yorks Waldorf Astoria hotel, in memory of the countrys first Catholic presidential candidate. Nobody aspiring to the White House would dream of missing it. In October 2000, George W. Bush only half joked: This is an impressive crowd the haves and the have-mores. Some people call you the elites; I call you my base. The remark had the merit of honesty, and could be applied to many a global leader around the world in many an era.

This is the topography of the global nomads they mix with a narrow group of similar-minded people, sparring with each other at the same auctions, fraternising on each others yachts. They compare themselves only against each other, which often leads to dissatisfaction with their lot, to the belief that they are not wealthy or powerful enough. They pay as little back to the state in tax as they can get away with. They reinforce each other in their certainties, convinced that their acquisition of wealth, and spending of it through charitable enterprise, have earned them their place at the apex of global decision-making and moral supremacy. Lloyd Blankfein, the chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs, spoke for many of his group when he famously quipped that he was doing Gods work.

Most of all, they are compulsively competitive in the making of money and the spending of it. The first stage after the acquisition of wealth is the flaunting. Opulence has been manifested differently over the ages, but the psychology underlying it has rarely changed. For slaves, concubines, gold and castles of ancient and medieval times, read private jets, holiday islands and football and baseball clubs of the contemporary era. For some that is enough. They shun the limelight, hiding behind the high walls of their mansions, indulging themselves and their small coteries of friends and hangers-on in discreet luxury.

At an early stage the laws of gravity intervene. The richer you are, the richer you become. Equally, the poorer you are, the easier it is to fall further. Investment advisers say that making the first ten million is the hard part. Once youve reached that milestone, beneficent tax regimes, lawyers and regulators will do the rest for you. The best brains follow the money, so the regulators earning a fraction of the incomes are no match for them. The plutocrats exhort the state to get off their backs and yet when the going gets tough the state is invariably their best friend, bailing out banks and other institutions deemed too big to fail. Profits are privatised, debts are socialised. As the American economist Joseph Stiglitz puts it: Much of todays inequality is due to manipulation of the financial system, enabled by changes in the rules that have been bought and paid for by the financial industry itself one of the best investments ever.

Now, as in centuries past, status symbols are not enough. Once satiated by wealth, they want more. Some (though not many) seek political office. One might think of Silvio Berlusconi. He has followed in the footsteps of Marcus Licinius Crassus. A safer, more plied, route is the businessman/banker who wields influence at one step removed not in secret, but not fully in the open either. Think Cosimo de Medici; think pretty much everyone who has acquired wealth and public profile in the modern day, from bankers to entrepreneurs to internet moguls. A seat on a government commission or cultural institution provides them with the respectability they crave, but also an assumption of vindication for their work.