Mission to China

Matteo Ricci and the Jesuit Encounter with the East

MARY LAVEN

For Jason, Daniel, and Benjamin.

Contents

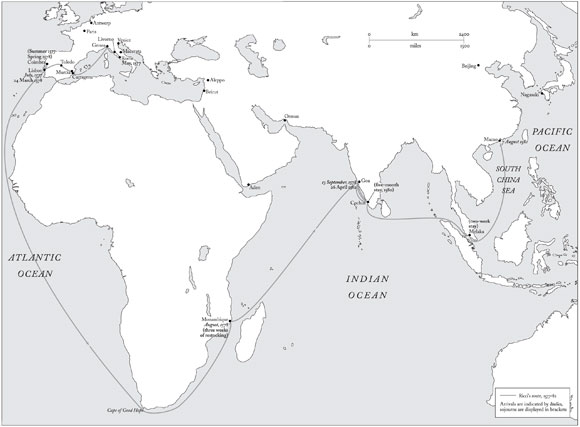

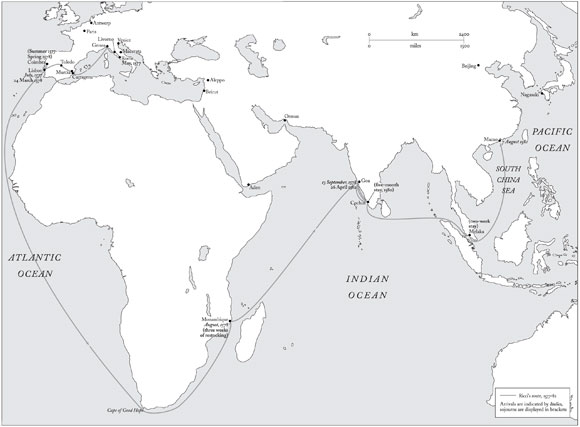

From Rome to Macao: Ricccis Voyage Out

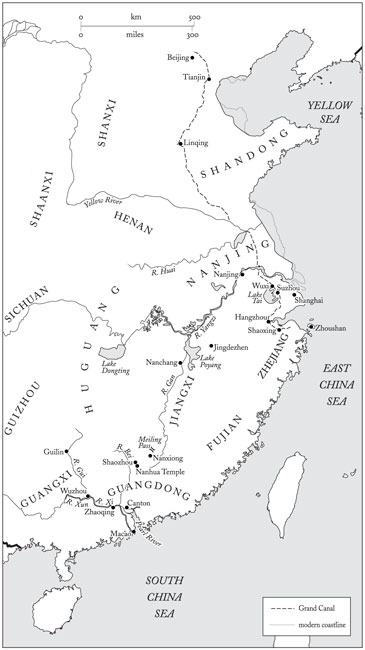

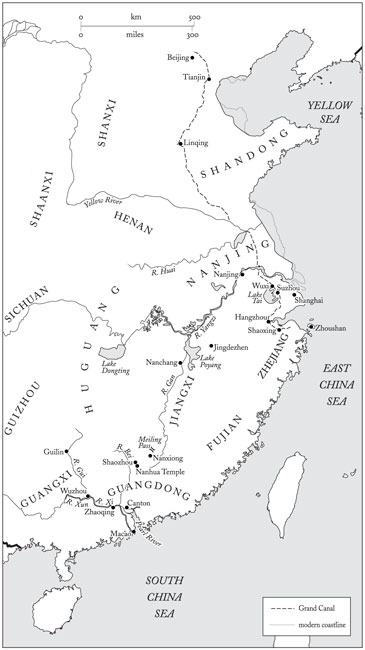

From Macao to Beijing: the Jesuits China

I have adopted the modern pinyin system of romanisation for the transcription of Chinese names and terms. There are a few exceptions. For example, I write of Canton rather than Guangzhou, because the former term was so resonant with Europeans who travelled to southern China during the period of the Jesuit mission. On the other hand, I have opted for Beijing rather than Peking (Riccis Pacchino), because the latter now sounds jarringly old-fashioned. Inevitably, alternative romanisations appear in some passages of quotation; I have silently emended these so as to avoid confusion.

Cambridge is a city in the south-east of Great Britain, the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire and one of the countrys oldest university centres. It is situated on the River Cam (actually a tributary of the River Ouse), 75 km north of London. There are 90,000 inhabitants (1981); the area of the city is 25 km2.

The city is surrounded by cultivated hills or flat plain (absolute height up to 70 m) traversed by rather shallow river valleys. The altitude of the hills and ridges is 1050 m, the summits of the hills are rounded or flat with gentle slopes. The predominant soil in Cambridge is boulder clay, with large areas of sand to the north of the city. When wet, the clay becomes waterlogged and severely impedes off-road movement of mechanised transport. The most important water obstacle in the city and its surroundings is the River Cam (or Granta), which is navigable north of Cambridge The rivers do not freeze and are in full flow all year round Practically all land surrounding the city is under cultivation, with crops of wheat, barley, potatoes and sugar beet Fields are bordered and roads lined with high hedges, which significantly impede observation of the countryside. A dense network of motor highways in the region of the city ensures the movement of transport in all directions throughout the year. The LondonCambridge motorway is dual carriageway with asphalt and ferro-concrete surfacing, each carriageway being 11m wide, with a dividing strip 2.55 m wide From the air Cambridge is easily recognised by its shape, its situation on the River Cam and the pattern of the road network Cambridge is an important scientific centre of Great Britain The Cambridge railway junction includes two stations, with comprehensive facilities and many warehouses, including storage for inflammable materials and lubricants.

These extracts come from an account of Cambridge published in 1989 to accompany a 1:10,000 city plan. It is one among many thousands of descriptions of cities and regions that were produced by the Soviet military authorities as part of their extraordinary and top-secret project to map the world. This global mapping project was underway before World War II, but intensified during the Cold War. In every embassy, a diplomat was given the responsibility of gathering as much information as possible regarding the topography of the land to which he or she was posted. All available published maps, guides, and directories were collected and sent to Moscow. In addition, any mode of espionage that might uncover the location of significant buildings, resources, and defence structures was encouraged. The plan that survives for Cambridge is fuller, more detailed, and more up to date than any Ordnance Survey map that was available at the time. It was also one of the last such maps to be published, since in the very same year the Berlin Wall came down, reorienting the world anew.

The sinister implications of the Soviet enterprise have faded fast. Since the first batch of secret maps was discovered in the early 1990s in Latvia, they have become collectors items, curios that provoke laughter more than fear. In the United Kingdom, their quaint transliterations (Perli for Purley, Sarri Doks for Surrey Docks) and occasional errors (Timlico for Pimlico) have attracted much discussion among amateurs of cartography. unarguably accurate, are eerily detached. The predominant soil in Cambridge is boulder clay. The rivers do not freeze and are in full flow all year round. Fields are bordered and roads lined with high hedges, which significantly impede observation of the countryside. These statements do not come readily to the mouth of a Cambridge-dweller.

Although belonging to a very particular moment in twentieth-century international relations, the Russian maps provide a striking comparison with a more remote episode in the history of global mapping. Five hundred years earlier, the world was riven by another iron curtain, which separated Europeans from the vast and secretive empire of China. The so-called Middle Kingdom, ruled by the Ming and rumoured to be extremely rich and highly civilised, was a land prohibited to foreigners. But in 1583 two men from Italy took a boat from Macao up the Pearl river and settled in the ancient city of Zhaoqing. The men who dared to penetrate the forbidden country were Jesuits, members of the recently formed Society of Jesus, and their intent was to convert the Chinese to Christianity. It was a plan perhaps no less brazenly imperialistic than that nurtured by the Soviet authorities in the twentieth century. In order to achieve their goals, the Jesuits (like Russian spies and diplomats) would need information. Thus they set about mapping the lands, customs and beliefs of the Chinese. Their accounts are inevitably those of outsiders. For all that the Jesuit missionaries were astute and conscientious observers, their attempts to make sense of (for example) Chinese religion or government would have seemed strangely alien to those whose practices they described. But that is not to say that their insights hold no validity, nor that relations between the missionaries and their would-be converts were as consistently chilly as the cold-war analogy might suggest. This then is a book about encounter and mutual perception: about the understandings and misunderstandings, conversations and confusions, descriptions and distortions that arose from the meeting of two worlds.

The two Jesuits who entered mainland China in 1583 belonged to an order that had originated among a group of students at the University of Paris fifty years earlier. There were ten companions to begin with: Ignatius (a former soldier from Loyola in the Basque country, who following a battle injury in 1521 had determined to devote himself to religion and learning), Francis Xavier (another Basque and Ignatiuss room-mate) and eight others, a majority of Iberians and a minority of Frenchmen. They spoke, they prayed, they planned, and one day, on 15 August 1534 (the Feast of the Assumption), they met in the Church of Saint Denis in Montmartre, bound themselves by vows of poverty and chastity and pledged to go to Jerusalem, or failing that wherever else the pope might direct them. Unable to obtain passage to the Holy Land, they went instead to Rome, where in 1539 they presented a proposal for a new religious order, the Society of Jesus, to Pope Paul III. Despite the objections of some cardinals, Paul was persuaded of the benefits of supporting this new order, distinguished as it was by its direct accountability to the papacy. There was even to be a fourth vow (in addition to the conventional obligations of poverty, chastity and obedience) that bound members of the order to journey anywhere in the world, when ordered to do so by the pope. According to the papal bull that gave formal approval to the Society in 1540, the purpose of the Jesuits was the propagation of the faith and the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine. In 1550, a further bull spelled out that the defence and propagation of the faith would include public preaching, lectures the

Next page