To Bethan Lily, Owen Thomas and Isaac Albert the new generation of Mounts

First published 2016

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright Toni Mount, 2016

The right of Toni Mount to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781445652399 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445652405 (eBOOK)

Typesetting and Origination by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A Year in the Life of Medieval England was conceived as a diary with entries covering events from AD 1066 to 1500, one for each day of the year, including 29 February. I tried to select a wide range of subject matter: from local news and weather reports to events of national significance; from poetry to health and gardening tips, songs and cookery recipes a mixture of items like those we might see today in newspapers and magazines. My aim has been to give the reader a taste of the lives and interests of the people in medieval England.

Court rolls, coroners rolls and wills give insights into the lives of the common folk and, usually being dated, were important sources for this book. Unfortunately, a few excellent stories were undated, so these havent made it into the diary. Occasionally, even big celebrity events, such as the death of King John, are given various dates in different sources, in which case I have made that clear.

As with any diary, there were dates when more than one event occurred; on other days nothing happened or at least nothing was recorded, insofar as I could discover in which case I took the opportunity to put in recipes or medical remedies appropriate to the season, instructions for bathing, comments on medieval sleep patterns or similar insights into everyday life.

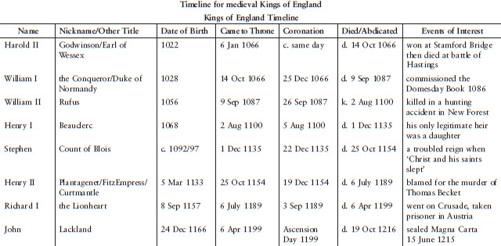

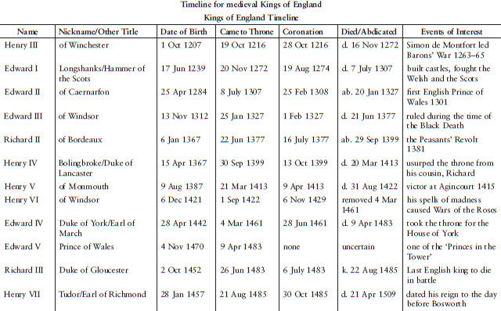

One possible problem for readers, with this day-by-day format, is that although the days are chronological, the years are not, so entries may leap from the eleventh century to the fifteenth, back to the twelfth and then forward again to the fourteenth. This was unavoidable and meant that a monarch might have died in April, been crowned in September and was born in November, so his story is told backwards. To aid the reader, I have included a timeline of English kings to provide a chronological framework against which other events can be set.

Most important to medieval folk, at a time when the great majority of the population was tied to the land, was the agricultural round of tasks through the seasons, as set down in this late fifteenth-century carol from a manuscript in the Bodleian Library, Oxford:

January By this fire I warm my hands,

February And by my spade I delve my lands.

March Here I set my things to spring,

April And here I hear the birds sing.

May I am light as bird on bough,

June And I weed my corn well enow.

July With my scythe my mead I mow,

August And here I shear my corn full low.

September With my flail I earn my bread,

October And here I sow my wheat so red.

November At Martinmas I kill my swine,

December And at Christmas I drink red wine.

J. L. Forgeng, Daily Life in Chaucers England

Also of significant importance in this historical period was the Roman Catholic Church, with its calendar of feasts and saints days, some of which I have included. Church laws controlled everyones lives. For example, you couldnt marry during Lent and on almost half the days in the year meat was supposed to be off the menu, although it is impossible to be certain just how strictly the rule was observed. For example, when Christmas Day fell on a Friday as it does in 2015 and did so in 1304, 1388, 1467 and 1472, for instance which took priority: the Chrismas boar or Fridays fast? I dont know the answer to that but I have tried to reflect some of these issues in my choice of material.

I had great fun compiling the entries and hope readers will enjoy this journey through the year, either as a dip-into book or as a trip back in time to meet our ancestors.

Toni Mount

December 2015

MEDIEVAL KINGS OF ENGLAND TIMELINE

JANUARY

1st A Day for Gifts

In medieval England, the day for giving and receiving gifts was 1 January rather than Christmas. The Ryalle Book, a manual for royal practices which dates to Edward IVs reign, explains how the king was to receive his New Year presents:

On New Years Day in the morning, the King, when he cometh to his foot-sheet, an usher of the chamber to be ready at the chamber door; and say: Sire, here is a years gift coming from the Queen. And then he shall say: Let it come in, Sire. And then the usher shall let in the messenger with the gift and then after that the greatest estates servant as is come, each after other as they be estates ; and after that done, all other lords and ladies after the estates that they be of. And all this while the King must sit at his foot-sheet. This done, the chamberlain shall send for the treasurer of the chamber and charge the treasurer to give the messenger that bringeth the queens gift, and he be a knight, the sum of ten marks, and he be a squire, eight marks, or at the least 100 shillings, and the kings mother 100 shillings, and those that come from the kings brethren and sisters, each of them six marks, and to every duke and duchess, each of them five marks, and every earl and countess 40 shillings. This being the rewards of them that bringeth the years gifts. For I report me unto the kings highness, whether he will do more or less: for this I know hath been done. And this done, the King to go make him ready, and go to his service in what array that him liketh.

On New Years Day 1464/65, Sir John Howard gave a gift of horses to King Edward IV and his queen, Elizabeth Woodville. The horses are even named in the Howard accounts: Lyard Duras (Lyard means grey) was a fine courser, costing 40; Lyard Lewes for the queen was worth only 8.

J. Ashdown-Hill, Richard IIIs Beloved Cousyn:

John Howard and the House of York

New Years Day (and Christmas and May Day too) was a time for medieval Mummers plays. These were free street theatre entertainments, although the players would pass around hats, pots and even ladles, hoping the audience would put in a few coins. A favourite play was that of St George in which the not-so-saintly knight fought and slew an assortment of enemies, from dragons and evil knights to Beelzebub. New Year was a popular opportunity for George to do his worst. Costumes were often very basic but the players either blackened their faces or wore masks it was a tradition since pagan times that they shouldnt be recognised, except as the character they played. The script was always in verse. Here is a brief excerpt from one of many versions, though no originals are extant: