Kelly Johnson, father of the Skunk Works Program.

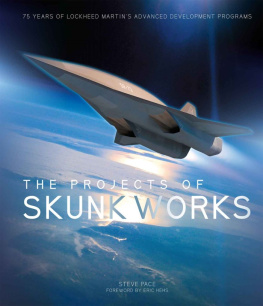

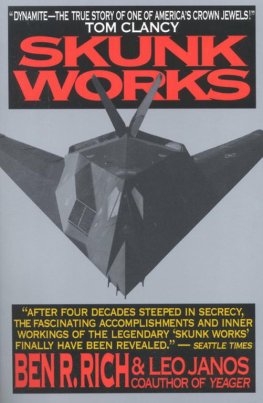

A nyone with even a mild interest in aviation has some knowledge of the Skunk Works. At the most basic level, the term connects with the highly secretive organization that developed and built the SR-71 Blackbird.

Growing up, a plastic kit model of that big black aircraft took the top center position on my bookshelf for many years. That childhood possession may have presaged my eventual career at the company that designed the aircraftor maybe it was the B-58 Hustler model next to it. Who knows?

The SR-71 Blackbird may have been the most prominent aircraft in the mind of the public, but it was not the first aircraft developed by the Skunk Works. As Steve Pace details in this book, that distinction belongs to the US Air Forces first operational jet-powered fighter, the P-80 (later known as the F-80 Shooting Star). The P-80 was followed by a number of groundbreaking aircraft including the T-33, F-94, F-104, C-130, and U-2, to name a few. The A-12 and YF-12 were direct predecessors to the SR-71.

And the SR-71 was not the last aircraft developed by the Skunk Works. The U-2R, F-117, F-22, and F-35 each have some or most of their roots in the Skunk Works.

These aircraft designations are just mile markers on highways built of details. The details can fill thousands of pages. Pieced together they can tell intricate stories about personalities, international and domestic politics, funding, design decisions, industry consolidation, and technical advances in everything from material science to digital electronics to software engineering.

The United States spent billions on the projects described here. People have devoted their lives to these projects and derived their livelihoods from them. A few of these efforts stretched the known state of the art. Some projects helped win wars. Others helped avoid them.

As someone who has covered Skunk Works topics as more or less an insider, I have a grasp of the editorial challenges the author faced in creating this book. The biggest challenges with writing projects like this tend to involve decisions on what to leave out. Theres not enough room for everything.

That filtering process begins before the point of collecting information and anecdotes. Details on some projects (and even entire programs) are withheld from public view primarily for reasons of national security, although corporate competitiveness also plays a role.

As the years progress, more information on these secretive programs becomes available to the public. At the same time, the Skunk Works adds to its long list of accomplishments. Together, these two factors explain why new books on the Skunk Works, like this one, are needed.

Not only does this book expand on the existing history of the Advanced Development Projects of Lockheed Martin, The Projects of the Skunk Works also preserves that history. Steve Pace deserves praise for keeping the conversation current and for encouraging new minds to take part in it.

INTRODUCTION

F irst and foremost, this authoritative work is not a history of the Lockheed Martin Corporation or any of its many predecessor companies. There are numerous other tomes specifically dedicated to those. Instead, this is a seventy-five-year history of the most clandestine entity of the Lockheed Martin Corporation, which is officially named Advanced Development Programs (ADP). Of course, ADP is much better known as the Skunk Works.

Close to seventy-five years ago now, on June 17, 1943, Lockheed Aircraft Corporation chief engineer Hall Livingstone Hibbard and propulsive system engineer Nathan C. Nate Price attended a top secret US Army Air Forces (USAAF) Air Technical Service Command (ATSC) meeting in Washington, DC. In attendance were Brig. Gen. Franklin Otis Frank Carroll; Cols. Marshall S. Roth, Howard Bogart, and Ralph P. Swofford Jr. (Lt. Col. Jack Carter later replaced Col. Swofford on this program); and then Capt. Ezra Kotcherproject officer and senior aeronautical engineer in the engineering division of the ATSCs Air Materiel Command (AMC). Hibbard and Price were told about gas turbine (turbojet) engine developments during this conference and prompted to submit a proposal for a pursuit (fighter) to be propelled by a single centrifugal-flow type of turbojet engine that had been designed by Maj. Frank Bernard Halford, a propulsive systems designer and engineer serving in the RAF. His engine was being produced at this time by the de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited in Great Britain as the Halford H.1B Goblin. This engine was to be produced as the J36 in the United States under license by the Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company.

The Bell Aircraft Corporation had been made aware of the H.1B Goblin engine earlier for use in its single-engine XP-59B derivative of the twin turbojetpowered P-59 Airacomet. The XP-59B was to be built under AMC Secret Project MX-398. It had acquired detailed H.1B specifications and drawings for this program. Bell, however, wouldnt be able to produce the XP-59B in satisfactory time, so the USAAF turned to Lockheed.

The primary reason the USAAF went to Lockheed was that on February 24, 1942, it had received an unsolicited proposal from Lockheed entitled Design Features of the Lockheed L-133 in a Lockheed report numbered 2571. At that time the L-133 was proposed to be a twin-engine fighter, powered by two Price-designed axial-flow turbojet engines, known in-house as the L-1000. This rather unique airframe and powerplant proposal was turned down, however, and Lockheed continued to manufacture piston-powered and propeller-driven combat and transport aircraft for the war effort.

So, on June 17, 1943, with full knowledge of Lockheeds interest in producing a turbojet-powered fighter, the USAAF correctly surmised that Lockheed would be interested in taking over for Bell. Hibbard was given the specifications and drawings related to the H.1B Goblin engine and headed back home to Burbank, California, where the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation resided. The program became known as AMC Secret Project MX-409.

Upon his return to Burbank, Hibbard and his chief of experimental design, Clarence Leonard Kelly Johnson, set their wheels in motion to generate an appropriate airplane. Two Lockheed reports associated with the MX-409 designnumbers 4199 and 4211, respectivelywere entitled Preliminary Design Investigation and Manufacturers Brief Model Specification. These were taken to the USAAF, and on June 17, 1943, Lockheed received a green light to proceed. On this very same day the USAAF issued Lockheed Letter [of intent to purchase] Contract Number W535 AC-40680. It called for the manufacture of one experimental pursuit airplane designated XP-80. As Lockheed had promised, and now by contract, the XP-80 was to be produced in about six months.