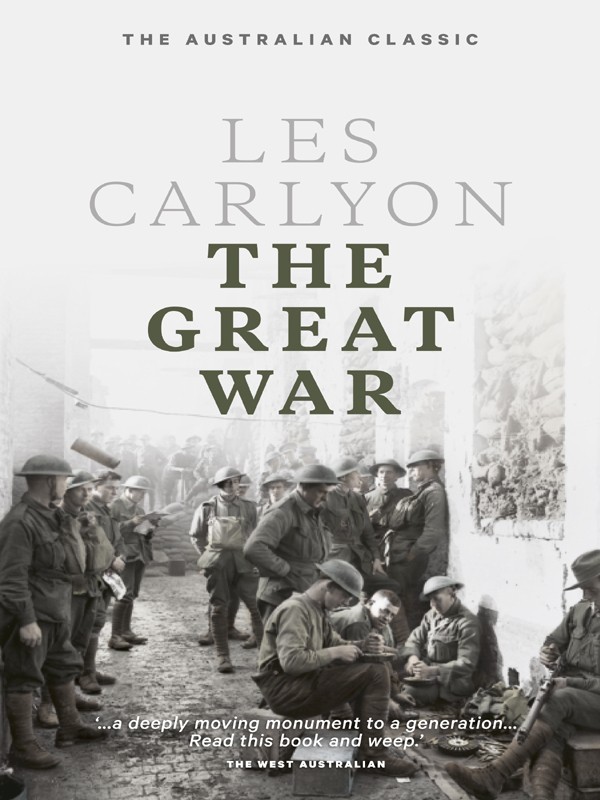

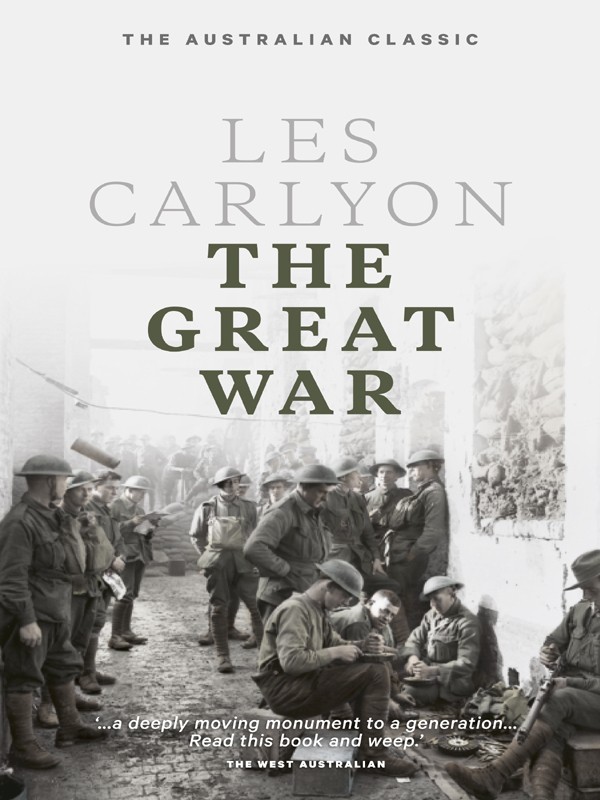

Les Carlyon was born in northern Victoria in 1942. He has been editor of the Melbourne Age, editor-in-chief of the Herald and Weekly Times group, as well as the winner of two Walkley Awards. Les Carlyons The Great War was published in 2006 to universal acclaim and became one of Australias non-fiction bestsellers. It was the joint winner of the inaugural Prime Ministers Prize for Australian History in 2007 and was honoured by the Australian Book Industry Awards, winning the Australian Book of the Year and the Best General Non-Fiction book.

The Great War is the sequel to Les Carlyons Gallipoli, published in 2001 to enormous critical and commercial success in Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain and now widely regarded as the most definitive history of the campaign yet written. Gallipoli won the Queensland Premiers Literary Award for Best History Book and the Australian Publishers Association Readers Choice Award. It has never been out of print and has sold more than 240,000 copies worldwide.

Also by Les Carlyon

Gallipoli

The Master

Imperial measurements have been used in this book as they were in documents and letters from the Great War. Exceptions to this are some gun calibres, which were measured in centimetres.

| 1 inch | 25.4 millimetres |

| 1 foot | 30.5 centimetres |

| 1 yard | 0.914 metres |

| 1 mile | 1.61 kilometres |

| 1 acre | 0.405 hectares |

| 1 centimetre | 0.394 inches |

| 1 metre | 3.28 feet |

| 1 metre | 1.09 yards |

| 1 kilometre | 0.621 miles |

| 1 hectare | 2.47 acres |

First published 2006 in Macmillan by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

This edition published in 2014 by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

1 Market Street, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2000

Copyright Les Carlyon 2006

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

ISBN 9781743535936

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available

from the National Library of Australia

http://catalogue.nla.gov.au

Typeset in Sabon by Post Pre-press Group

Printed by McPhersons Printing Group

Maps by Map Illustrations (maps@mapillustrations.com.au)

The author and the publisher have made every effort to contact copyright holders for material used in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked should contact the publisher.

Papers used by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

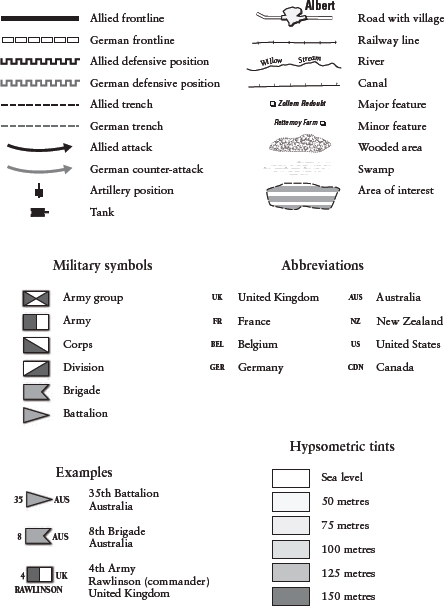

List of maps

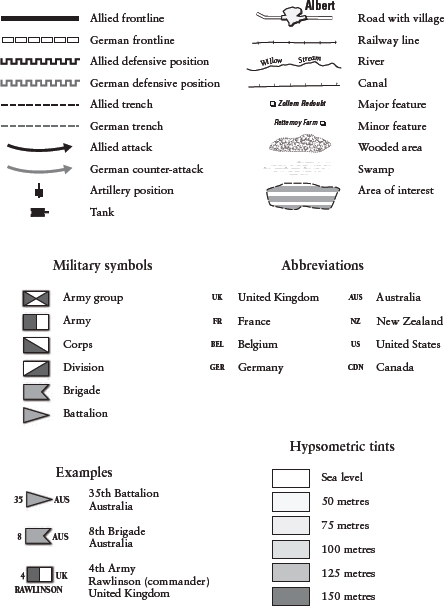

Key to maps

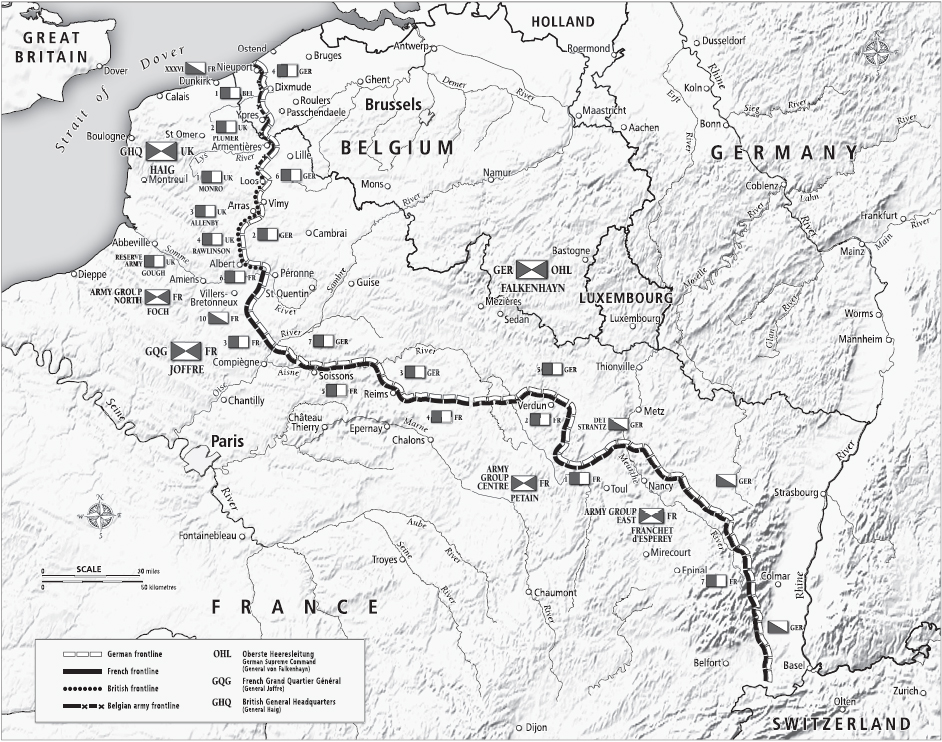

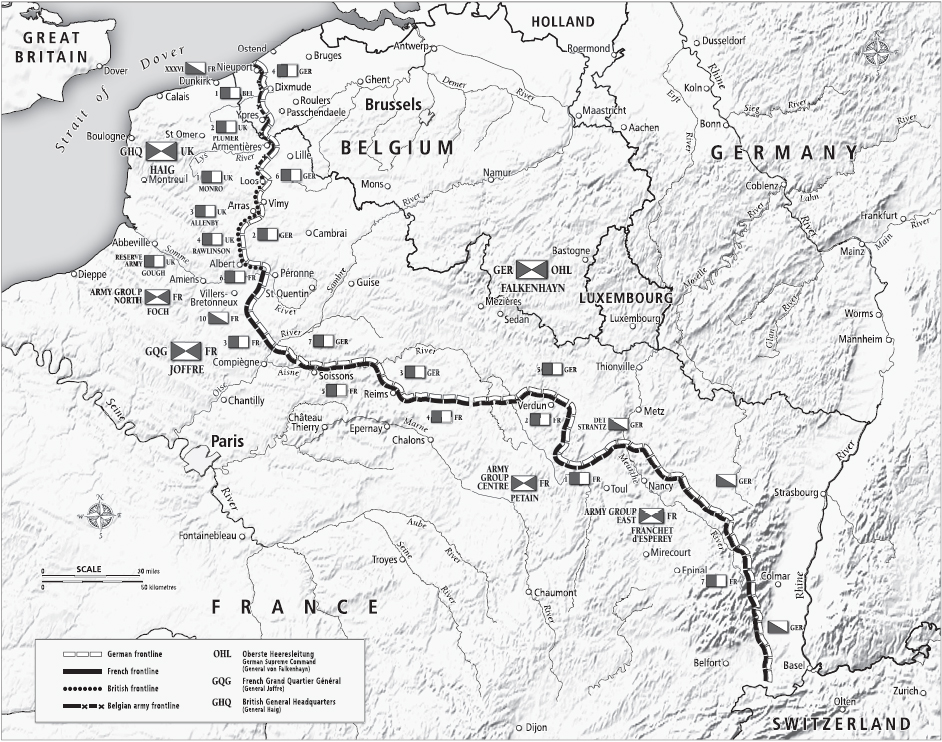

The trench stalemate, July, 1916

P ROLOGUE

In the gloaming

Here dead lie we because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

A. E. Housman

T here were so many of them, more than three hundred thousand, and we never really saw them. Not when it mattered to see them anyway, not when they were doing the things that marked them as different, then and now, from the rest of us.

Here they are resting during a lull in one of the Somme battles, their boots sprinkled with white dust. Some drag on cigarettes, lumpy and hand-rolled. One daydreams and another, eyes big, face like a slab of marble, just stares, not at the landscape, not at the shell holes that sit lip to lip like sores, but at some panorama that exists only in his mind and now holds him prisoner. One re-reads a cutting that his mother has sent him from the Ballarat Courier. Another scribbles with an indelible pencil worn so short that it needs to be gripped with the thumb and forefinger in a taut circle. He adds three or four lines to what he wrote the night before. Itseems important to write things down. It makes the absurd seem real. You could see the German shells in the sky at the top of their arc. Others saw them too. And writing makes events seem less terrible. If you can write about them, they are at least imaginable. One man, propped on his elbow, tries to doze, his helmet tilted over his eyes, a sprig of hair fluffing out one side. Another peers at the tear in his trousers as though it is a personal insult. The barbed wire has brought up a blood-stippled welt on his thigh. In this war it is nothing much. Some of the mens faces carry the soft contours of youth but sometimes the eyes look older than the faces.

They are stretched out on the downs, these men, on those redbrown earths shot through with lumps of chalk, rich dirt, soft country, nothing like home. Back there the soils were thin and hungry, as if some earlier civilisation had worn them out and left, so that all the ground could push up now was scraggy gums. But at least Australian soils smelled sweet. They didnt reek of explosives and wet sandbags and decomposing bodies that would swell up, then turn black and, if left, become huddles of khaki or grey that hid a jumble of bones, joined here and there by scraps of gristle and blown by the winter winds.

Anyone coming upon this group resting on the Somme would know at once that they were Australians. They had a look to them. There was a lankiness, a looseness in the way they moved that was occasionally close to elegance but not quite soldierly. War and the old world of Europe had failed to impose all of its formalities on them. They were good at war but in a way that offended the keepers of the orthodoxies: lots of dash, not much discipline away from the battlefield. They were good at war but they didnt want to stay in the army once the fighting ended. They were all volunteers. This was an interlude, not a career. When it was over they would go back to being commercial travellers and science teachers, farmers and bank clerks. In 1918 two architects, an orchardist and a grazier commanded four of the five Australian divisions. The corps commander, an engineer from a family of Jewish immigrants that had settled in Melbourne, also had degrees in law and arts, played the piano, sketched and wrote.

We, their kin and countrymen, didnt see the Australians when they were roistering in the cafs of Poperinghe, behind the Belgian front, where vin blanc was rhymed into plonk and used to wash down eggs and chips. We didnt see them when they sauntered around Horse Guards in London, eyes wide, because these were men from a land where the most ancient public buildings were little more than 100 years old and werent well loved anyway, since they belonged to a convict society that was best not talked about. We didnt see them queuing outside the theatres or riding in taxis, carelessly spending their pay, which was much higher than that of their British cousins. We didnt see them watching the morning horsemanship in Hyde Park and smiling at the primness of it all. These tourists wore slouch hats and woollen tunics that ballooned over their hips, partly because the pockets always seemed to be full of tins and pouches. They tended to be taller than Englishmen and used slang words that had no currency outside their homeland. They seemed to be alive with the hopes of the New World and careless when it came to the protocols of the old. They didnt expect too much from life: that was the way of people then. They wore shoulder badges that said Australia, and these really werent necessary. Their look, those languid poses, gave them away. They didnt call themselves Diggers: that came later.

Next page