The members of the 332d Fighter Group and the 99th, 100th, 301st, and 302d Fighter Squadrons during World War II are remembered in part because they were the only African American pilots who served in combat with the Army Air Forces during World War II. Because they trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field before and during the war, they are sometimes called the Tuskegee Airmen. In the more than sixty years since World War II, several stories have grown up about the Tuskegee Airmen, some of them true and some of them false. This paper focuses on eleven myths about the Tuskegee Airmen that, in light of the historical documentation available at the Air Force Historical Research Agency, and sources at the Air University Library, are not accurate. That documentation includes monthly histories of the 99th Fighter Squadron, the 332d Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group, the 332d Fighter Groups daily narrative mission reports, orders issued by the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces, Fifteenth Air Force mission folders, and missing air crew reports.

1. The Myth of Inferiority

2. The Myth of Never Lost a Bomber

3. The Myth of the Deprived Ace

4. The Myth of Being First to Shoot Down German Jets

5. The Myth that the Tuskegee Airmen sank a German destroyer

6. The Myth of the Great Train Robbery

7. The Myth of Superiority

8. The Myth that the Tuskegee Airmen units were all black

9. The Myth that all Tuskegee Airmen were fighter pilots who flew red-tailed P-51s to escort bombers

10. The Myth that Eleanor Roosevelt persuaded the President to establish a black flying unit in the Army Air Corps

11. The Myth that the Tuskegee Airmen Earned 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses during World War II

Myth 1

The first misconception regarding the Tuskegee Airmen was that they were inferior. The myth was that black pilots could not perform as well in combat as their white counterparts. This misconception developed even before the 99th Fighter Squadron deployed as the first African American Army Air Forces organization in combat. On October 30, 1925, the War College of the U.S. Army issued a memorandum entitled, The Use of Negro Manpower in War. The memorandum noted that Negroes were inferior to whites and encouraged continued segregation within the Army. Even during the squadrons operations in North Africa, authorities challenged its right to remain in combat.

In September 1943, Major General Edwin J. House, commander of the XII Air Support Command, sent a memorandum to Maj. Gen. John K. Cannon, Deputy Commander of the Northwest African Tactical Air Force, suggesting that the 99th Fighter Squadron had failed to demonstrate effectiveness in combat, and should be taken out of the combat zone. The memorandum was based on information from Col. William Momyer, commander of the 33rd Fighter Group, to which the 99th Fighter Squadron had been attached.

Following the House memorandum, which went up the chain of command all the way to the headquarters of the Army Air Forces, the Statistical Control Division, Office of Management Control, War Department, conducted an official study to compare the performance of the 99th Fighter Squadron with that of other P-40 units in the Twelfth Air Force. The subsequent report, released on March 30, 1944, concluded that the 99th Fighter Squadron had performed as well as the other squadrons.

As you can see from the table below, there were seven fighter groups of the Fifteenth Air Force flying primarily bomber escort missions between June 1944 and the end of April 1945. In terms of aerial victory credits, which is one good measure of combat performance, the 332d Fighter Group did not score the lowest number. In fact, its total number of aerial victory credits was higher than that of two of the white groups.

Table I: Fighter Groups of the Fifteenth Air Force in World War II

Organization | Aerial victories June 1944April 1945 |

1st Fighter Group | |

14th Fighter Group | |

31st Fighter Group | |

52d Fighter Group | 224.5 |

82d Fighter Group | |

325th Fighter Group | |

332d Fighter Group | |

Sources: USAF Historical Study No. 85, USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World War II (Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978); Maurer Maurer, Air Force Combat Units of World War II (Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1983).

I should mention, however, that both of the groups scoring lower numbers of aerial victories than the Tuskegee Airmen in the same period were flying P-38 aircraft, and the 332d Fighter Group was flying, for all but one month of the period, P-51 aircraft, which had a higher speed and range than the P-38s. Of the four P-51 fighter groups in the Fifteenth Air Force, the 31st, 52nd, 325th, and 332nd, the 332nd Fighter Group shot down fewer enemy aircraft in the same period. It is possible that the Tuskegee Airmen shot down fewer enemy aircraft than the other P-51 fighter groups, and did not have any aces, because they were staying closer to the bombers they were escorting, as ordered, and not abandoning the bombers to chase after enemy aircraft in the distance. Twenty-seven of the bombers in groups the 332d Fighter Group was assigned to escort were shot down by enemy aircraft. The average number of bombers shot down by enemy aircraft while under the escort of the other groups of the Fifteenth Air Force was 46. The Tuskegee Airmen lost significantly fewer bombers than the average number lost by the other fighter groups in the Fifteenth Air Force.

Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis Sr., the first African American general in the U.S. Army, awards the Distinguished Flying Cross to his son, Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., for a mission the younger Davis led on June 9, 1944.

Myth 2

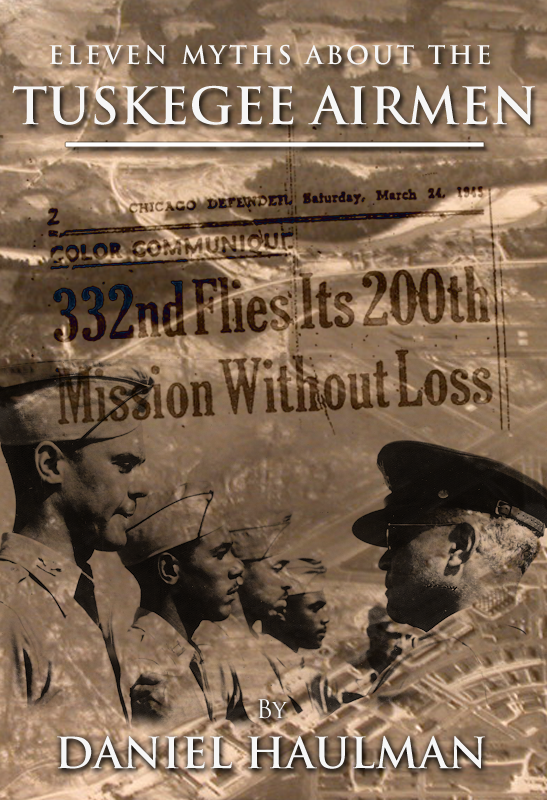

Another misconception that developed during the last months of the war is the story that no bomber under escort by the Tuskegee Airmen was ever shot down by enemy aircraft. A version of this misconception appears in Alan Gropmans book, The Air Force Integrates (Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1985), p. 14: Their record on escort duty remained unparalleled. They never lost an American bomber to enemy aircraft. This misconception originated even before the end of World War II, in the press. A version of the statement first appeared in a March 10, 1945 issue of Liberty Magazine , in an article by Roi Ottley, who claimed that the black pilots had not lost a bomber they escorted to enemy aircraft in more than 100 missions. The 332d Fighter Group had by then flown more than 200 missions. Two weeks after the Ottley article, on March 24, 1945, another article appeared in the Chicago Defender , claiming that in more than 200 missions, the group had not lost a bomber they escorted to enemy aircraft. In reality, bombers under Tuskegee Airmen escort were shot down on seven different days: June 9, 1944; June 13, 1944; July 12, 1944; July 18, 1944; July 20, 1944; August 24, 1944; and March 24, 1945. Moreover, the Tuskegee Airmen flew 311 missions for the Fifteenth Air Force between early June 1944 and late April 1945, and only 179 of those missions escorted bombers.