Jacques Lacoursire and Robin Philpot

A Peoples

History

of Quebec

SEPTENTRION

SEPTENTRION

Baraka Books and Les ditions du Septentrion thank the Canada Council for the Arts for the support provided for the translation of this book from French to English.

ditions du Septentrion thanks the Canada Council for the Arts and the Socit de dveloppement de entreprises culturelles du Qubec (SODEC) for the support provided to its publishing program, and the Government of Qubec for its Programme de crdit dimpt pour ldition de livres. We also acknowledge the financial assistance of the Government of Canada through its Canadian Book Publishing Development Program.

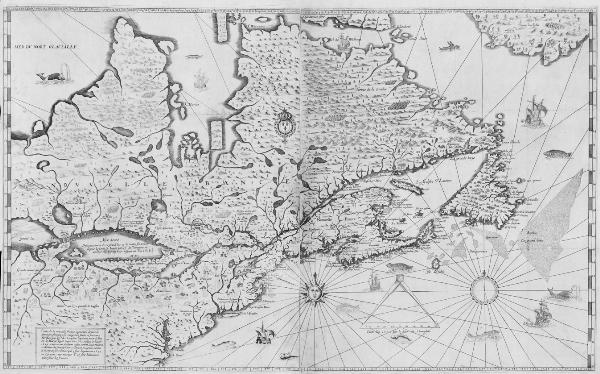

Cover: Samuel de Champlains 1632 map of New France, in Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France occidentale dicte Canada.

Inset from left to right: Port of Montreal in 19th century, based on lithography by Duncan, Toronto Public Libarary; Battle of Saint-Eustache, 1837, National Archives of Canada; Ren Lvesque at victory celebration, November 15, 1976.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Lacoursire, Jacques, 1932-

A people's history of Quebec / Jacques Lacoursire and Robin Philpot; translated by Robin Philpot. Translation of Une histoire du Qubec. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-926824-14-7

1. Qubec (Province) - History. I. Philpot, Robin II. Title.

FC2911.L3413 2009 971.4

C2009-903650-9

Legal Deposit 3rd quarter 2009

Bibliothque et Archives nationales du Qubec

Library and Archives Canada

Translation and adaptation by Robin Philpot

ePub conversion by Studio C1C4

Baraka Books

6977, rue Lacroix

Montral, Qubec

H4E 2V4

Telephone: 514-808-8504

info@barakabooks.com

www.barakabooks.com

Les ditions du Septentrion 1992

1300, av. Maguire

Sillery, Qubec

G1T 1Z3

www.septentrion.qc.ca

Original first edition: Une histoire du Qubec raconte par Jacques Lacoursire , Septentrion 2002.

Trade Distribution & Returns

LitDistCo

C/o 100 Armstrong Ave.

Georgetown, ON

L7G 5S4

Ph: 1-800-591-6250

Fax: 1-800-591-6251

orders@litdistco.ca

Map of New France by Samuel de Champlain, published in Paris in 1632. When the Kirke brothers, privateers from Dieppe, captured the habitation at Quebec, Champlain returned to Europe and struggled to ensure that France recovered its colony. This map was published to support his work.

CHAPTER 1

Hard Slow Beginnings

The history of Quebec began formally on Friday, July 24, 1534. Ship captain Jacques Cartier sent his seamen ashore at the end of the Gasp Peninsula to erect a cross bearing an escutcheon with three fleurs-de-lis and a plate where it was engraved Vive le roi de France. Jacques Cartier described the scene in his log. Once the cross was raised, we knelt down and joined hands before it in worship. The French visitors used signs to explain what the ceremony was about and pointed to the heavens above whence cometh our redemption.

Cartiers Iroquoian hosts did not realize that in fact the cross-raising ceremony was a formal way of claiming possession of their land on behalf of the King of France. Nor did they know that the Europeans believed they could take over any portion of land that did not already belong to a Christian Sovereign. Their chief Donnacona sensed nonetheless that something serious was amiss. For Donnacona and his people Mother Earth belonged to everybody and these visitors from France had not requested permission to erect the cross. When Donnacona paddled out to meet the French ship, he insisted that the land belonged to them and that Cartier should have asked for permission. Cartiers answer was a half truth, but a whole lie. He claimed that the cross was nothing more than a beacon indicating the entry to the harbour. Cartier then brought two of Chief Donnaconas sons on board and, as was the custom, took them back to France to prove he had reached new lands.

Jacques Cartier, who was long considered to have discovered Canada, was not really the first European to reach what is now known as Quebec. For decades French, English, Portuguese, Spanish, Basques, and Northern Europeans had fished cod on the grand banks off Newfoundland. Cod was a staple for all Catholics. In those days Catholics were bound to abstinence for 140 days every year. Eating meat was a mortal sin on those days and fish was the only substitute allowed.

Long before Europeans had ever reached the continents to which they gave the name America in 1507, the land had been inhabited for tens of thousands of years. The St. Lawrence Valley was settled a little later than elsewhere since it took longer for the glaciers to melt and for the Champlain Sea to recede. Depending on the region, archaeological research shows human occupation of the land dating back eight toten thousand years.

The two Iroquois people Cartier brought to France sparked considerable interest, especially when they were paraded before the Kings Court. They soon learned the rudiments of French and were astonished by the way Europeans raised their children. Corporal punishment was commonplace in France whereas children in Aboriginal North American society were never reprimanded physically.

Jacques Cartier set out in 1535 on a second expedition to what Europeans considered to be the New World. His two Aboriginal guestsor captivesspoke of a river that would take him deep into the interior of the continent. As for other explorers, he hoped to find a route to China, the land of spices the value of which had shot up after the Ottomans had seized Constantinople in the middle of the 15 th century.

The French sailed upriver as far as Stadacona, later to be called Quebec. Stadacona was at the heart of a region known as the Kingdom of Canada, with Canada being a place name of Iroquoian origin meaning a village or group of houses. After a brief visit to the large Aboriginal town of Hochelaga on the island of Montreal, Cartier and his men settled in to face the rigours of their first North American winter. Early in May 1536 before weighing anchor for France, he erected another cross with the French coat of arms and the Latin inscription, Franois I reigning by the grace of God, King of the French. This was in fact a second claim to possession of the land.

Along with the Spanish and the Portuguese who had established settlements in America, the French hoped to settle the St. Lawrence Valley. In 1541, Jacques Cartier was appointed second in command to Jean-Franois de La Rocque, sieur de Roberval, and they crossed the Atlantic again bringing hundreds of settlers with them, many of whom came straight from prison. Cartier returned hastily to France however, believing that the gold and diamonds he had in his ship would be proof of the riches in the New World. Roberval had reached Newfoundland by then and was preparing to sail upriver. This second attempt to settle was also doomed to fail and the failure was compounded by the fact that Cartiers riches were nothing but fools gold and quartz.

Thus ended the first chapter in the history of the formal French presence in Quebec. More than half a century went by before other plans were hatched to settle the St. Lawrence River Valley. Lack of a settlement did not mean however that the St. Lawrence was abandoned during that period. The Basques and the French continued to conduct fur trading and fishing expeditions, and rivalry was intense. In 1587, for instance, two of Jacques Cartiers great-nephews, Jean and Michel Nol, were confronted with competing traders along the river.

SEPTENTRION

SEPTENTRION