ALSO BY JANIS OWENS

My Brother Michael

Myra Sims

The Schooling of Claybird Catts

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2009 by Janis Owens

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or

portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address

Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of

The Gale Group, Inc., used under license

by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008032676

ISBN-13: 978-1-4391-0056-1

ISBN-10: 1-4391-0056-X

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

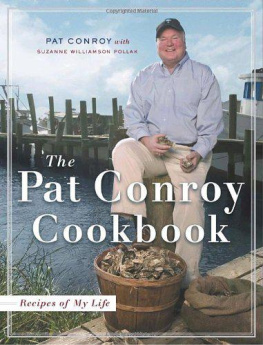

This book is for my father, foremost: Roy Junior Johnson, son of the South and Old Testament Prophet Extraordinaire. Also in honor of our great family cooks: Mama and Grannie and Big Mama; Aunt Doris and Aunt Izzy, Dessie and Grannie Hart; Jeana, Laurabell, and Burgerinawho taught me more lessons than I can remember, in the kitchen and every other room in the house. And finally, for Arkansas Wendel and my literary brothers, Pat Conroy and the late (and great and dearly grieved) Doug Marlette, whose unending delight in our shared Southern history informs this work.

Grace and peace to all of you, and to Daddy: Proverbs 20:7.

A truer verse, there never was.

What cracker is this same that deafs our ears with this abundance of superfluous breath?

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, KING JOHN, ACT II, SCENE 1, 1594

CONTENTS

I t was my great friend Doug Marlette who first brought me news of the amazing Florida novelist Janis Owens. He had met her at a book festival when he was publishing his first novel, The Bridge, and called to tell me he had found a new best friend for both of us. He was reading her first novel, My Brother Michael, and he didnt understand why Janis Owens wasnt famous. When I asked what was so great about her, Doug mentioned her pure authenticity, her comfortableness in her own skin, and her amazing gifts at storytelling. As Doug knew, I have a primordial attraction to the storytellers of the world. I ordered her three novels that night, and by the time I met Janis, I had read My Brother Michael, Myra Sims, and The Schooling of Claybird Catts. The three novels were an astonishment and a dilemma for me. She wrote about the hookwormed, xenophobic redneck South that has received such incessant ridicule in the literature of the South (including my own works) and in Hollywood movies that shiver with pleasure when their villains speak with those phony Southern accents. Janis used the term Cracker with affection and great understanding, and as I read her, I understood that she was awakening ghosts in my own kingdom that I would sooner or later have to interrogate if I was ever to understand the reign of both beauty and confusion in the life of my own mother, Peg Conroy. When I finished reading the three books, I called Doug Marlette and echoed his question: Why isnt Janis Owens world famous?

When I read her cookbook, it was a revelation. She would refer to herself and her family as Crackers and Rednecks with pride and affection and a great tenderness. If I had ever called my family or my cousins rednecks, I think it doubtful that my mother would have talked to me again. Though my mother hailed from an Alabama family whose Cracker credentials were in perfect order, she spent much of her energy and all of her life in denial of this unassailable fact. She became a brilliant historian of her own life, and almost nothing she said about herself was true.

After my mother read Gone With the Wind, and after her total immersion in the character of Scarlett OHara, my mother reinvented herself. The young girl who had previously answered to the name of Frances changed her middle name to Margaret and ordered her family to call her Peggy, after her new heroine Margaret Peggy Mitchell. I learned this story on the day we buried my mother in the Beaufort National Cemetery. It was the same day my grieving stepfather, Dr. John Egan, said between sobs that it was such an honor to be married to a Southern aristocrat. My mother was an open-field runner against her past. Because I adored everything about her, I think I let her turn me into the same thing.

Janis Owenss cookbook is a love letter written to celebrate the poor white people of the American South who were my mothers people and my own. Since Janis is incapable of writing a bad sentence, her cookbook is a joy to read and a pleasure to return to again and again. She has produced a Cracker Escoffier, or a White-Trash Julia Child, that is hilarious and charming. Her tour of Southern food seems definitive to me. She does not gussy up any of her recipes for stylistic or culinary reasons. It makes you hungry just to flip through the pages of this high-spirited and user-friendly book. It also took me to long-forgotten memories of my past.

Ive often written about my mothers failure as a Southern cook. As a housewife in the fifties, my mother discovered the labor-saving pleasures of frozen food. Even today, I cannot pass a frozen chicken-pot pie without becoming bulimic. My brother Mike has a freezer full of them and eats them with relish whenever he feels nostalgic for Mom. Frozen macaroni and cheese is an abomination unto the Lord to me. When I escaped my mothers kitchen and entered The Citadel, I discovered that I had never eaten spinach, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, and a whole produce department of other vegetables. Most cadets complained bitterly about the food in the mess hall, but I thought it was the finest food I had ever eaten, a cornucopia of guilty pleasures to discover and savor.

Yet, Janiss book caused me to remember some of the Southern dishes that my mother did well in the early years of her marriage. She could make perfect cornbread in a black skillet, and her fruit pies were legendary. Once a week, she composed a velvety lemon bisque that I could have inhaled with a straw. But it was in Piedmont, Alabama, and Orlando, Florida, that I feasted on the foods that Janis so lovingly describes in this cookbook. In Piedmont, my aunts and cousins would cook for hours preparing lunch for the men still in the fields. The meals were enormous, sensuous, and completely satisfying. Throughout the meal the women would burst out of the kitchen with some new steaming vegetable or fresh supply of biscuits. The gravies were heavenly, the fried chicken indescribable. Those were some of the happiest meals of my childhood.

In Orlando Aunt Helen and Uncle Russ would invite my family to the picnics at their Baptist church, and again, the recipes of Janis Owens were spread before my eyes in what seemed like endless profusion. When I asked my mother why Baptists ate so much better than Roman Catholics, she told me to shut up. I begged Aunt Helen to invite us to every church picnic that the Baptists organized, and if so, I promised not to fidget when she read from the Bible to my cousins, the Harper boys, each night. In Orlando I learned about congealed salads, aspics, deviled eggs, cole slaw, country ham, fried catfish, and dozens of other dishes that I had never encountered before. When we left Orlando, I thought that Baptists were the happiest, most well-fed people on earth. Later Id tell my mother that I was thinking of becoming a Baptist so I would have lifetime access to those picnics, but Mother told me to hush up; if my father heard me, hed kill me. I never brought up the subject again.