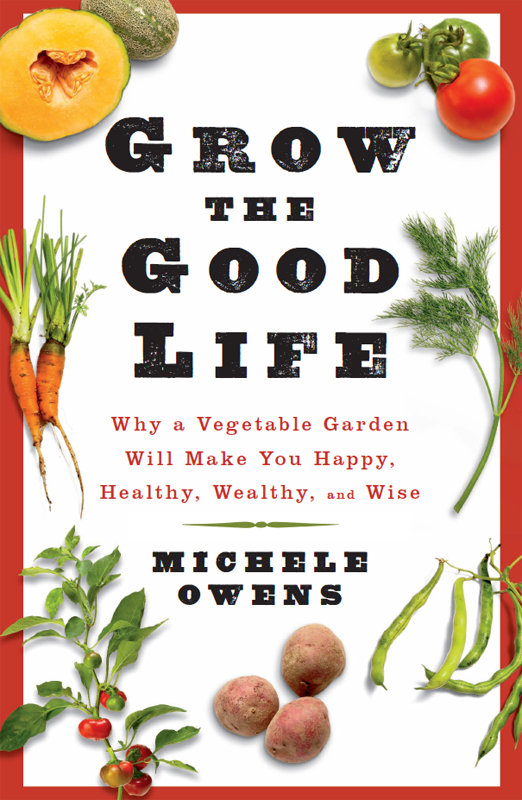

For Milo, Georgia, and Grace

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

What Ive Hauled Out of the Garden

2 MONEY

Better Than Berkshire Hathaway Stock Bought in 65

3 FLAVOR

If You Havent Grown It, You Havent Tasted It

4 HEALTH

Eternal Youths Not in a Fountain, But in a Garden

5 THE SOIL

Why Dirt Isnt Dirty

6 BEAUTY

Prettier Than Sod and Shrubs Any Day

7 THE KIDS

What Theyll Take Out of the Garden

8 THE NEVER-ENDING EDUCATION

Why Youll Soon Be as Much of an Expert as Any Expert

9 SURVIVAL

How to Stay Adaptable in Uncertain Times

10 HAPPINESS

The Best Reason to Garden

INTRODUCTION

What Ive Hauled Out of the Garden

I wrote this book to help people see how easy and how rewarding it is to grow beautiful food. Those ideas seem obvious to me, now that Ive spent the last 18 years considering my vegetable garden one of the great joys of my life. However, they are clearly not obvious to many of my neighbors, who look at me with some degree of puzzlement whenever they see me out with my shovel.

America in the early 21st century is definitely not a gardening culture, but it may well be on its way to becoming one, and Id like to give that transformation a definite shove. I hate to think of anybody deprived of such a source of pleasure as a vegetable garden just because he or she doesnt know where to begin.

Let me tell you how I got started. I certainly belonged to the ranks of the super-ignorant when I made my first garden, but it was not a gradual process of enlightenment that turned me into a backyard farmer. It was one single moment of towering pique, at 3:00 p.m. on a miserably cold January afternoon in 1993.

Yes, the ground was frozen, and yes, it would be another 3 months at least before anyone could push the first peas into the earth, but no matter: I was transformed in the dead of winter at the Grand Union supermarket in the rural village of Cambridge, New York. My husband and I had people coming over for dinner that night, and I was horrified to discover the limits of the produce department in January. My choices were wilted cabbage, rubbery carrots, soft potatoes, or hari-kari.

I was doubly horrified because Id recently dragged my husband out of New York City, which he loved, and talked him into buying an old house upstate because I needed something I couldnt put my finger on that I couldnt find in New York: light, air, soil, something. We were in our early thirties and married only a few years. Jeff was miserable in the country, so I was miserable.

My beloved husbands grim mood was not all that was getting me down, either. It had taken me a long time to find a job in the uncongenial labor market of Albany, New York, and the one Id found was with such uniquely seamy peopletheyd soon be investigated for running a pyramid schemethat I shuddered every time I entered their office building. The heating bills for the decrepit 200-year-old house wed bought because it was cheap and beautiful and had a center hall big enough to drive a truck through were arriving like body blows. The thermometer seemed to be reaching below minus 30 every night, such extreme cold that your nose hairs would freeze instantly the moment you stepped outside.

And the discovery that our sufferings were going to include no food worth eatingwell, that was just too much for me. A nice dinner at the end of the day is to me what I imagine church on Sunday is to the faithful: the minimum requirement to keep my spirits from dragging entirely on the ground.

This will not stand, I vowed there in the produce aisle of the Grand Union, a newly minted revolutionary with a bunch of limp carrots in her fist.

That spring, I made my first garden. I was so stupid about the task at hand that my husband actually had to show me how to use a shovel. Still, I was in such a rage to lay in some decent ingredients for a change that I managed to rip 60 square feet out of the lawn with a pick, an unbelievably arduous job.

I didnt plant muchonly the holy triumvirate of basil, tomatoes, and arugula. But they grew and were gorgeous and delicious and gave me beautiful salads and pesto for months. My ambitions were stoked. The next spring, we hired a guy with a tractor to dig a much bigger garden. My husband, a little more used by then to his country exile, bought me a very romantic birthday presenta truckload of mushroom compostand I was off and running, a full-fledged backyard farmer who rarely ate any vegetable she wouldnt try to grow.

The Grand Union supermarket chain, on the other hand, which condescended so unforgivably to its rural customers, soon entered bankruptcy and then disappeared as a freestanding company. I like to think I had a hand in that.

I started gardening because I wanted better-tasting food, and I certainly took that out of my garden, in floods. What I didnt expect were the many other things Ive taken out of my garden besides beautiful meals. I discovered that I loved the exercise of digging and that it made a nagging pain in my shoulder disappear. I loved the way the garden looked. I loved the way it smelled. I got intense pleasure from the creatures who shared my gardentoads, birds, and spectacular yellow and black garden spiders that would set up shop among my greens. I liked the way the seasons followed each other in the garden, each with its own purpose. I liked managing early crops and late crops, with one replacing another like a symphony. After eating my beautiful food, I liked turning the stuff other people threw awayapple cores, carrot ends, potato peelingsinto compost that would yield beautiful food again. My garden gave me a profound sense of connection to the whole cycle of life. In the garden, I always felt happy.

The other thing I didnt know when I began was how seamlessly my garden would fit into the normal insanity of modern life. From the time I made my first garden, I not only worked like mad at various jobs, I had three babies, sold my house and bought two others, acquired various cats, dogs, hens, and goldfishand yet became so slick and efficient as a backyard farmer that every year I produced more food in less time.

In fact, Ive taken so much out of my vegetable garden over the years for such limited effort on my part that Ive long considered non-gardeners faintly crazy. Now, however, we are arriving as a nation at a political, economic, epidemiological, and environmental moment when it clearly is crazy not to grow a little food.

As I write this, we are struggling to emerge from the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Millions of jobs have been lost; the values of homes and retirement accounts have plummeted. And food prices, which soared with the oil price spike in 2008, remain highwhile a package of vegetable seeds is still one of the worlds great bargains.

Of course, money is not the only reason why it makes infinite sense at this particular moment for more of us to become gardeners. Our current food system represents a fifth of Americas fossil fuel consumption, an enormous contributor to the environmental and political anguish associated with this countrys carbon habit. Industrial farmings overreliance on artificial fertilizer made from natural gas not only gives every radish a watermelon-sized carbon footprint, but the excess nitrogen from this fertilizer also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and flows into rivers and oceans, where it causes algae to bloom and fish to die. Commercial farming compromises our water supply by sending pesticides and salts into itand by consuming enormous amounts of water to make large-scale production possible, for example, in an arid place like Californias Central Valley. The giant machines used in farming destroy the structure of the soil by compacting it and lead to erosion. To call industrial farming an ecological disaster is understating the case. Meanwhile, the backyard vegetable garden requires not a drop of oil or grain of artificial fertilizerabsolutely nothing whatsoever out of balance with nature.

Next page