TO OUR PARENTS. AND SPECIAL THANKS TO CAROL FOR ALL YOUR GREAT WORK ON THIS BOOK.

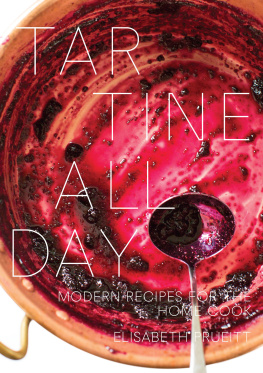

Text copyright 2006 by Elisabeth M. Prueitt and Chad Robertson.

Photographs copyright 2006 by France Ruffenach.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4521-3610-3

The Library of Congress has previously cataloged this title under ISBN-13: 978-0-8118-5150-3

Designed by Vanessa Dina

Typesetting by Janis Reed

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

The word authentic has been overused by food writers, who have turned it into a catchall term of praise for just about anything that tastes good, especially if a grandmother is hovering somewhere in the recipes back story. But whenever I see this word, another similar word springs to mindauthorand the food I recognize as authentic is real food that is unmistakably its creators own, as genuine as a manuscript in its authors own handwriting. Such food is rare, so when I first saw the handmade fruit tarts and loaves of bread from the wood-fired brick oven of Elisabeth Prueitt and Chad Robertson, I did an excited double take.

That was nearly ten years ago, when Liz and Chad had already started their tiny Bay Village Bakery in Point Reyes Station in Marin County. Twice a week, they hauled their bread to the Berkeley farmers market in big, eye-catching vintage wooden boxes, and before long Berkeley shoppers were queuing up for bread before the market had even opened. The bread was that good. It had that remarkable village-bakery quality that comes from stone-ground organically grown flour, native yeasts, coarse gray sea salt, a wood fire, and loving hands. Call it authenticity. I went to see the bakery soon after. It was in a little Victorian cottage, and the brick oven was in a fifteen-foot-square kitchen in the back of the house, where Chad baked as much as he could in the limited space.

At the time I was summering in the fog of Bolinas, a seaside village not far from Point Reyes Station, where I was reading a wonderful memoir, Life la Henri, by the French chef Henri Charpentier. I was so caught up in Charpentiers vivid descriptions of his apprenticeship in the kitchens and markets of France almost a hundred years ago that I couldnt help drawing negative comparisons between the food of then and now. But I made an immediate exception for Liz and Chads bakery. I remember thinking that their little tarts and rustic loaves would have been right at home in Henris world, a world where freshness was measured in hours rather than days or weeks and where honest food was grown and prepared by human handsa world that, even in France, has largely disappeared.

The Japanese designer Eiko visited me in Bolinas that same summer, and because I wanted to surprise her with something unexpected and beautifulno easy task, Eiko having one of the more exacting and exquisite aesthetic sensibilities I have ever encounteredI took her to the bakery one afternoon. Liz was stacking boxes of apricot tarts to take to market; I remember the sun was streaming down and the apricots were glistening, their edges just slightly caramelized, and Eiko was ravished. The whole magic tableau said everything that needs to be said about food and the joy of living.

Ive never been much of a baker or pastry cook, and so whenever family birthdays rolled around, I came to entrust Liz and Chad with baking the cake, one of which in particular floats into my minds eye (and onto my minds palate) as a kind of Platonic ideal of a birthday cake: layers of airy cake separated by thinner layers of strawberry jam; a rose geraniumflavored red wine syrup; just enough perfectly whipped cream; and little sprigs of just-picked fraises des bois, the fragile, intensely aromatic European woodland strawberries that are rarely grown in California gardens, arranged around the glazed top. It is a cake so classically restrained in appearance and so impetuously romantic in flavor that it is the finest birthday present I can imagine receiving.

More birthdays have raced by, and today Liz and Chad are the proud proprietors of the bustling San Francisco establishment that gives this book its name. On the surface, Tartine may appear to be the urban antithesis of the bucolic Bay Village Bakery. Its not just that the bakery is several times larger than their old one; Tartine is also a corner caf in a cosmopolitan neighborhood densely populated with the young, the restless, and the ambitiously hip. Yet Liz and Chad have preserved their quiet artisanal authority without making any aesthetic compromises. The desserts at Tartine are full of light and air at the same time. The bakery is lavish in the use of seasonal fruit, judicious in its deployment of sugar and decoration, and, best of all, nearly all the ingredients used are grown nearby and produced sustainably, so that everything that comes out of the kitchen is fresh, unfussy, simple, and alive.

In short, Tartine is about as authenticand as indispensableas a bakery and caf can get. No wonder people are still lining up.

Alice Waters

FOREWORD

The word authentic has been overused by food writers, who have turned it into a catchall term of praise for just about anything that tastes good, especially if a grandmother is hovering somewhere in the recipes back story. But whenever I see this word, another similar word springs to mindauthorand the food I recognize as authentic is real food that is unmistakably its creators own, as genuine as a manuscript in its authors own handwriting. Such food is rare, so when I first saw the handmade fruit tarts and loaves of bread from the wood-fired brick oven of Elisabeth Prueitt and Chad Robertson, I did an excited double take.

That was nearly ten years ago, when Liz and Chad had already started their tiny Bay Village Bakery in Point Reyes Station in Marin County. Twice a week, they hauled their bread to the Berkeley farmers market in big, eye-catching vintage wooden boxes, and before long Berkeley shoppers were queuing up for bread before the market had even opened. The bread was that good. It had that remarkable village-bakery quality that comes from stone-ground organically grown flour, native yeasts, coarse gray sea salt, a wood fire, and loving hands. Call it authenticity. I went to see the bakery soon after. It was in a little Victorian cottage, and the brick oven was in a fifteen-foot-square kitchen in the back of the house, where Chad baked as much as he could in the limited space.

At the time I was summering in the fog of Bolinas, a seaside village not far from Point Reyes Station, where I was reading a wonderful memoir,

Next page