Table of Contents

2008 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2008

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lombardo, Paul A.

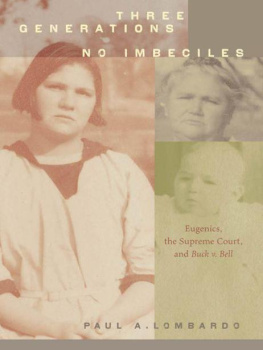

Three generations, no imbeciles : eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell / Paul A. Lombardo. p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8018-9010-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 978-0-801-89881-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Buck, Carrie, 1906-1983Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Sterilization (Birth control)Law and legislationVirginia. 3. Insanity (Law)Virginia. I. Title. II. Title: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell .

[DNLM: 1. Buck, Carrie, 1906-1983. 2. Sterilization, Involuntarylegislation & jurisprudenceUnited States. 3. EugenicshistoryUnited States. 4. Eugenics legislation & jurisprudenceUnited States. 5. History, 20th CenturyUnited States. 6. Sterilization, InvoluntaryhistoryUnited States. WP 33 AA1L842t 2008]

KF224.B83L66 2008

344.73048dc22 2008006546

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book, For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516- 693 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible. All of our book papers are acid-free, and our jackets and covers are printed on paper with recycled content.

For AJL and DAL

INTRODUCTION

I Wanted Babies Bad Woman Told of Her Sterilization

Charlottesville (VA) Daily Progress, February 24, 1980.

That headline interrupted my breakfast one day in 1980, and it continues to echo more than twenty-five years later. At the time I had only a passing acquaintance with the U. S. eugenics movement, but I would soon learn that its legal high point was the 1927 United States Supreme Court case of Buck v, Bell, Carrie Buck was sterilized following the Courts validation of a Virginia law mandating the surgery for people who had been declared socially inadequate. The article in my morning newspaper mentioned the case and explained the lawsuit that had been filed to overturn it. Carrie Bucks sister Doris was quoted in the article; she joined the new lawsuit because she had been sterilized also.

Thinking this story might provide the topic for a seminar paper, I finished my coffee and hurried to the universitys library. Finding the case was easy enough; reading it took even less time, because what is now widely considered one of the most infamous decisions in Supreme Court history is also one of its shortest. With scandalously little justification, and in an opinion of less than three pages, the Court approved the power of a state to erase the parental hopes of its unfit citizens.

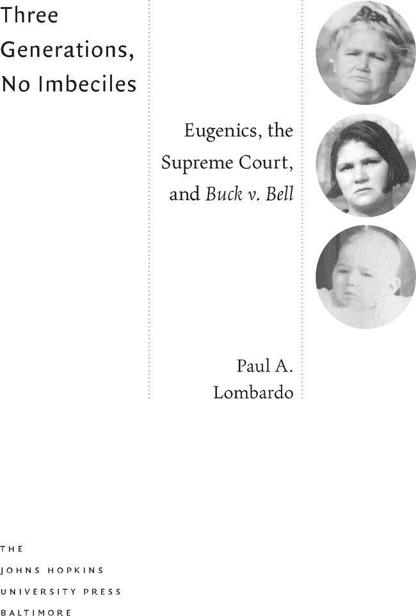

Despite its brevity, the opinion was too powerful to be ignored. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., then the most celebrated judge in America, wrote it. He was famous for pithy legal maxims, and the Buck case provided an occasion to live up to that reputation. It is better for all the world, said Holmes, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. Carrie, her mother, and Carries illegitimate infant fit Holmes category of the manifestly unfit, all touched by mental and moral defect. He did not hesitate to declare his conviction: Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

A famous judge, a Supreme Court decision, an over-the-top sound-bite in the opinionsurely this was worth writing about. I leapt into the research, which revealed that Carrie Buck, a poor girl, was separated from her family at an early age and was living quite literally on the wrong side of the railroad tracks. Not long after she turned sixteen, she got pregnant; when the pregnancy became obvious, she was sent away to a state institution. Like other girls sent to the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, Carrie was thought to be mentally defective and was considered a moral degenerate.

Virginia enacted a eugenic sterilization law in 1924, just in time for Carries arrival at the Colony. The law was based on the theory that defectscriminality, poverty, illegitimacy, and the likewere passed down from people like Carrie to their children. The Colony was founded as a place to shut such people away to live celibate, childless lives. Carries mother was already there, accused of being a prostitute and pauper. Carries baby, barely six months old, also qualified for a spot at the Colony. Experts had examined the infant, saying she was below average and not quite right, setting the stage for Holmes to condemn all three generations of the family. The Buck case confirmed the theory of hereditary defect, providing legal approval for operating on more than sixty thousand Americans in over thirty states and setting a precedent for more than half a million other surgeries around the world.

I completed the paper, but I couldnt let go of the story. Too many questions remained. Was this case an honest legal test of eugenical theory, or was it merely a charade put on by self-proclaimed Progressive social engineers? Was Carrie Bucks problem too little mental power or too much sex? How could seven other Supreme Court Justices, including William Howard Taft and Louis Brandeis, join Holmes in his caustic decision without one word written in dissent?

For the next two years I mined the papers of the lawyer who orchestrated the Buck case and completed a thesis that explained his role in writing the sterilization law and being its advocate in court. Then I went on to law school myself, but I soon stole time from my studies to find Carrie Buck and talk with her in the last weeks of her life. A tiny obituary in the same local paper that had first introduced us drew me to her funeral, where the handful of mourners made no mention of her past shame.

By then, even more driven to understand how this case had come about, I found Carries grade school report cards and her daughters honor roll record, proving the Holmes opinion false. Years later, I found the photos of the infamous three generations buried in the archives of a former eugenics expert; that collection showed how he had manufactured evidence to fit the states case against Carrie Buck. Other research revealed handwritten minutes of an official meeting between Carries appointed lawyer and her adversaries. Those records confirmed that the case was not just a tragedy. It was a legal sham.

The evidence presented at Carrie Bucks trial was transparently weak; with even a modest amount of effort, a competent lawyer could have challenged both the scientific premises of the Virginia sterilization law and the description of Carrie Bucks family offered by the state. But that defense never materialized, in large part because Carries lawyer had no intention of defending her. He offered no rebuttal to the states arguments for surgery; he called no witnesses to counter the experts who had condemned the Buck family; he never explained that Carrie had not become a mother by choice, but that she had been raped.

That lawyer, Irving Whitehead, was a founding member of the Virginia Colonys board of directors and a major supporter of the sterilization campaign of Dr. Albert Priddy, the Colonys superintendent. Following his failure at trial, Whitehead secretly met with Priddy and the Board and voiced satisfaction that the case was proceeding as planned. He had betrayed his client, defrauded the court, and set in motion a series of events that history has uniformly condemned.