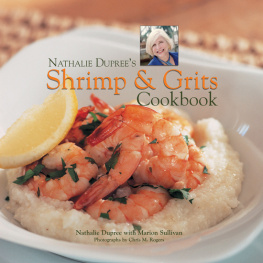

Photographs 2006 Chris M. Rogers

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Introduction

Shrimp and grits, one of the Souths beloved foods, leaves a lingering taste and a folkloric mystique that borders on the mythical. Each community and ethnic group along the regions shorelines brings its own cultural influences to this dish.

A carriage driver in Charleston might tell visitors romantic tales about shrimpers heading out before dawn and using their catch for a tasty and nourishing early breakfast of shrimp and grits.

Others might imagine Native Americans bringing their corn to the Jamestown, Virginia colony and adding tiny local shrimp to their corn mush. No one really knows how the combination of shrimp and grits first came about.

We do know, however, that starting in early colonial days, many Carolina lowcountry inhabitants were dependent on fish and shrimp for food. Some form of grits have been around since before the Native Americans greeted the first white man with rockahominie (the Native American name for cracked corn; hence, we think, hominy). Grits are produced by grinding or pounding dried corn into pieces.

People who grew up on the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts remember catching the tiniest and most flavorful of shrimpcreek shrimpin the salt marshes and rivers and bringing them home to top their grits, unshelled, slathering everything with butter and pepper, and relishing them all together for breakfast. Perhaps they added a tad of hot sauce, or cooked up some country ham and made some brown sauce, or added some greens from last nights supper, and poured all that over the shrimp and grits.

Now, the crme de la crme of New Southern chefs combine grits, shrimp and a variety of ingredients from crisp bacon to finely chopped truffles, with more than fifty restaurants in Charleston, South Carolina, alone serving their own version of shrimp and grits. Some go so far as to grind dried corn and make their own grits or hominy. Youll find many of their recipes, easily done by the home cook, in this book.

Throughout much of the history of Southern cookery, grits have been eaten as a staple with a variety of seafood. Among the Jewish immigrants who settled in small Southern towns a century or so ago, some housewives served grits with fried salt herring, soaked overnight in water to leach out the brine, then fried in butter. My husband, Jack Bass, remembers this childhood dish as delicious.

Grits are embedded in the regions bi-racial culture and celebrated in poetry, song, and story. There is even an annual grits festival in the town of St. George, South Carolina. An award-winning film, Its Grits, produced by South Carolina filmmaker Stan Woodward, captures the historic place of grits within the Souths popular culture.

Grits, says Southern food writer John Egerton in Side Orders, are an all-purpose symbol for practically anything of importance to Southerners. They stand for hard times and happy times, for poverty and populism, for custom and tradition, for health and humor, for high-spirited hospitality. They also stand for baking, broiling, and frying. After a bowl of grits, we half expect to find the day brighter, the load lighter, the road straighter and wider.

While attending the St. George Grits Festival, I found all sorts of grinders for the fresh-milled corn, and purchased a number of different ones to use while testing these recipes. (I did not, however, join in the grits weighing contest, where contestants roll in a bathtub of cooked grits and then are weighed to see how much grits stuck to them.)

Various kinds of quick grits were used in testing recipes and developing this book. Most quick grits are lye-based. Others are freshly milled but are ground more finely and cook more quickly than stone-ground grits. Almost any grits can be ground finer in a food processor. No instant grits were used to test these recipes.

Nathalie Dupree

Charleston, SC

Shrimp & Grits Basics

How Shrimp Are Sold

While shrimp may be sold simply as small, medium, large, and jumbo at the seafood market or grocery store, the origin for these designations is a commercial grading system. The parameters are somewhat loose, but on average small has 50 to 60 shrimp to a pound, medium 36 to 50, large 21 to 35, and jumbo 16 to 20. The very biggest can be as large as 5 shrimp to the pound. When substituting a different size of shrimp in a recipe, check what size the recipe calls for and adjust the cooking time accordingly.

Most retail shrimp are sold headless. Occasionally, what looks like a bargain can be found: heads-on fresh shrimp at less than half the headless price. However, the discarded weight of the heads will almost equal the higher price for heads-off and the purchaser or cook will have the task of beheading the shrimp. So it is probably no bargain. The task of snapping off the head is worth it to many because fresh heads-on shrimp are one of the real treats of the sea. To tell just how fresh a shrimp is with a head on, look for its whiskers or antennae. They are prone to fall off as the shrimp ages more than a few hours off ice, or 12 hours or so after being caught. The heads are wonderful for stock and some people like eating the cooked head meat.

As for the sometimes black vein down the back of a shrimp, which is its digestive tract, some people see no need to remove the vein if they dont think it is sandy. Some chefs insist on having it removed with a pin, toothpick, or a plastic shrimp peeler that removes the shells at the same time.

Kinds of Shrimp and Where They Come From

Those who live on the shore consider fresh shrimp to be those which are not more than 12 hours old. Shrimp this fresh are considered a luxury food, whether you catch them yourself or buy them at a commercial shrimpers dock. In the South, wild shrimp spawn in the saltwater marshes along the Carolina and Georgia coasts and along the Gulf shores. People with access to tidal creeks or marshes will go out during shrimp season with a seine or drop net and catch the small shrimp during their journey to the sea. These creek shrimp at their finest have a fragile, edible shell and a sweeter taste that aficionados prefer. When they have grown to the size of a thumbnail, the shrimp start to wind their way through the brackish sluices and marsh grass toward the saltwater where they will mature and grow.

Wild Gulf and South Atlantic Coast brown, pink, and white shrimp are among the finest in the world. These names dont clearly describe them, since most shrimp change color according to bottom type and water clarity. The scientific names are: Brown: Farfantepenaeus aztecus; Pink: Farfantepeneus duorarum; and White: Litopenaeus setiferus.

In addition, there is domestic shrimp farming and an abundant supply of imported frozen shrimp available throughout America.