Published in 2017 by the Feminist Press

at the City University of New York

The Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5406

New York, NY 10016

feministpress.org

First Feminist Press edition 2017

Copyright 2017 by Brittney C. Cooper, Susana M. Morris, and Robin M. Boylorn

Lucille Cliftons poem wont you celebrate with me from The Book of Light is reprinted on page 111. Copyright 1993 by Lucille Clifton. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Copper Canyon Press, www.coppercanyonpress.org.

All rights reserved.

This book was made possible thanks to a grant from New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

No part of this book may be reproduced, used, or stored in any information retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

First printing January 2017

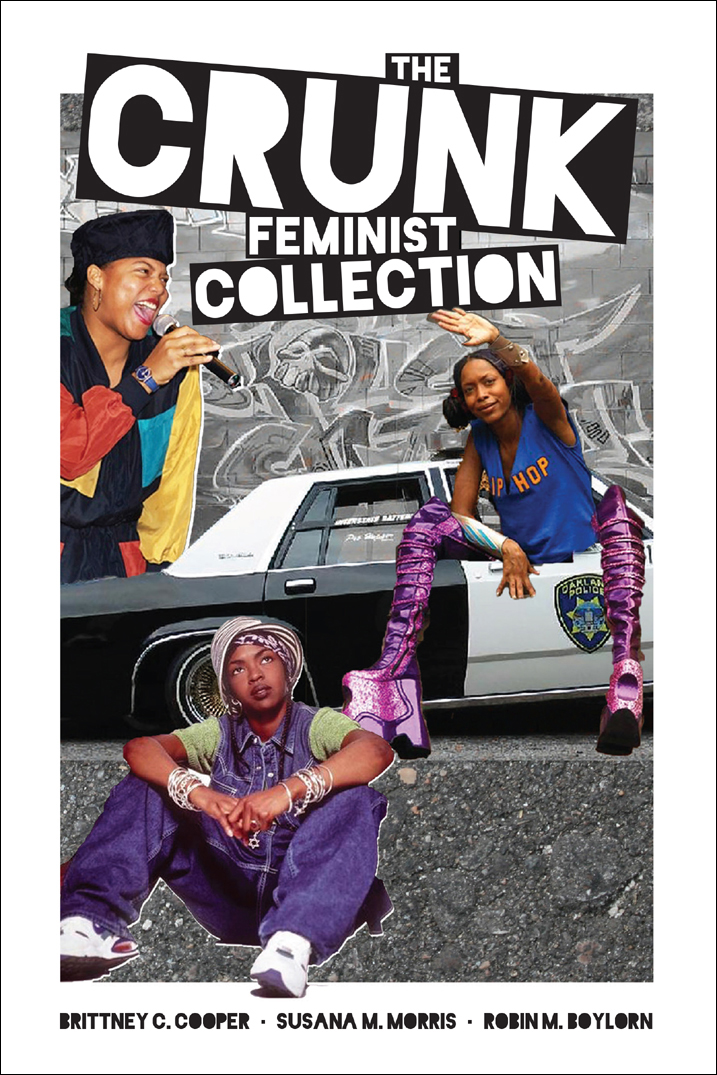

Cover design by Elise Peterson

Text design by Sarah Evelyn Castro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title.

For our mamas, our homegirls, and each other

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

The Crunk Feminist Collective (CFC) will create a space of support and camaraderie for hip hop generation feminists of color, queer and straight, (with)in the academy and without, by building a rhetorical community, in which we can discuss our ideas, express our crunk feminist selves, fellowship with one another, debate and challenge one another, and support each other, as we struggle together to articulate our feminist goals, ideas, visions, and dreams in ways that are both personally and professionally beneficial.

The CFC aims to articulate a crunk feminist consciousness for women and men of color who came of age in the hip hop generation by creating a community of scholar-activists from varied professions who share our intellectual work in online blog communities, at conferences, through activist organizations, and in print publications, and who share our commitment to nurturing and sustaining one another through progressive feminist visions. This collective is a forum where we seek to speak our own truths and to both magnify and encourage the feminist credos that shape and inform our lives and that we use to engage and transform our world. Crunk feminism is the animating principle of our collective work together and derives from our commitment to feminist principles and politics and also from our unapologetic embrace of those new cultural resources, which provide or offer the potential for resistance. Crunk(ness) is our mode of resistance that finds its particular expression in the rhetorical, cultural, and intellectual practices of a contemporary generation.

Beat-driven and bass-laden, crunk music blends hip hop culture and Southern Black culture in ways that are sometimes seamless but more often dissonant. Its location as part of Southern Black culture references the South both as the geography that brought many of us together and as the place where many of us still do vibrant and important intellectual and political work. The term crunk was initially coined from a contraction of crazy or chronic (weed) and drunk and was used to describe a state of uberintoxication, where a person is crazy drunk, out of their right mind, and under the influence. But where merely getting crunk signaled that you were out of your mind, a crunk feminist mode of resistance will help you get your mind right, as they say in the South. As part of a larger women of color feminist politic, crunkness, in its insistence on the primacy of the beat, contains a notion of movement, timing, and of meaning-making through sound that is especially productive for our work together.

Percussion by definition refers to the sound, vibration, or shock caused by the striking together of two bodies. Combining terms like crunk and feminism and the cultural, gendered, and racial histories signified in each is a percussive moment, one that signals the kind of productive dissonance that occurs as we work at the edges of disciplines, on the margins of social life, and in the vexed spaces between academic and nonacademic communities. Our relationship to feminism and our world is bound up with a proclivity for the percussive, as we divorce ourselves from correct or hegemonic ways of being in favor of following the rhythm of our own heartbeats. In other words, what others may call audacious and crazy, we call crunk because we are drunk off the heady theory of feminism that proclaims that another world is possible. We resist others attempts to stifle our voices, acting belligerent when necessary, and getting buck if and when we have to. Crunk feminists dont take no mess from nobody!

The Crunk Feminist Collective, 2010

We are hip hop generation feminists. We unapologetically refer to ourselves as feminist because we believe that gender, and its construction through a White, patriarchal, capitalist power structure, fundamentally shapes our lives and life possibilities as women of color across a range of sexual identities. We are members of the hip hop generation because we came of age in one of the decades, the 1990s, that can be considered post-soul and postcivil rights. Our political realities have been profoundly shaped by a systematic rollback of the gains of the civil rights era with regard to affirmative action and reproductive justice policies; the massive deindustrialization of urban areas; the rise and ravages of the drug economy within urban, semiurban, and rural communities of color; and the full-scale assault on womens lives through the AIDS epidemic. We have come of age in the era that has witnessed a past-in-present assault on our identities as women of color, one that harkens back to earlier assaults on our virtue and value during enslavement and imperialism. Our era has likewise been marked by an insidious reimagining of earlier forms of violence to include the proliferation of stereotypes, both from the public sphere and from our communities, which have now named us welfare queens, quota queens, baby mamas, hoochies, gold-diggers, wifeys, bitches, hoes, and tricks, along with a range of (un)creative rhetorical permutations.

We identify with hip hop because the music, the culture, the fashion, and the figures provide the soundtrack to our girlhood and our young womanhood. Our coming-of-age happened in the linguistically and rhetorically rich cultural milieu and transformation that was the 1990s, the decade of the woman, but also the decade of the female emcee: Queen Latifah, MC Lyte, Da Brat, Left Eye (and TLC), Foxy Brown, Lil Kim, and Lauryn Hill. We not only jammed to new jack swing, we reveled in the beats of new jill swing too, because we understood what Queen meant when she sang, In a nineties kind of world, Im glad I got my girls. We witnessed Puffy invent the remix, Mary J. Blige pioneer hip hop soul as she looked for a real love, and FUBU start a global Black fashion trend that was for us by us. We were captured by Darius and Nina falling in love, breaking up, and falling in love again, even as we observed that the art of