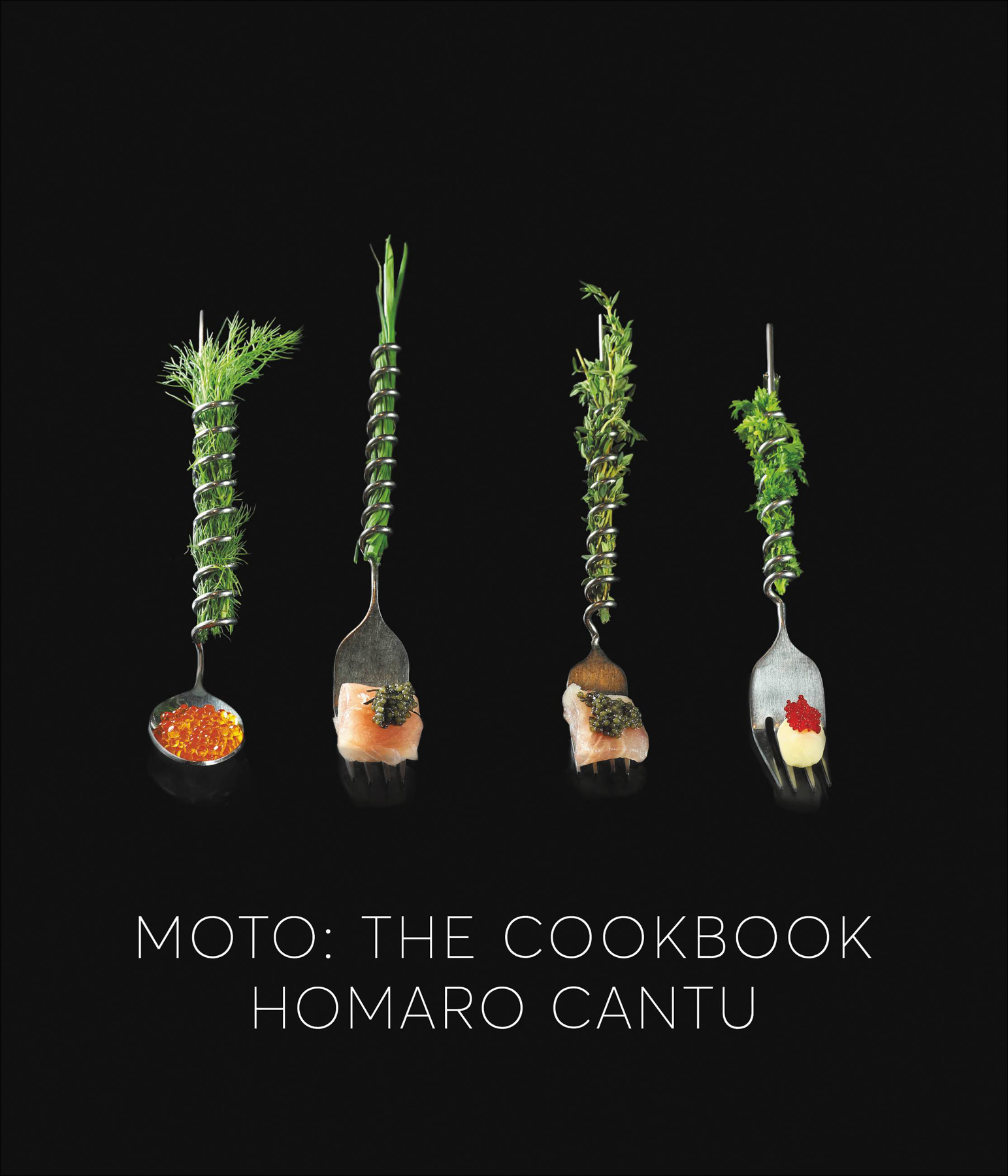

Homaro Cantu was one of the worlds most dazzling culinary artists, known for modernist cooking techniques that boggled the mind and tasted exquisite. Moto, his restaurant in Chicago, was a fine-dining destination, starred by the Michelin guide, and a home for the worlds most creative cooks.

But growing up, Omar didnt have a kitchen. Frequently homeless as a youth, his first taste of fish came while he was living in the woods with his mother. He hated it; he didnt know you had to remove the scales and bones. As an adolescent, he narrowly avoided the juvenile detention center.

But he was saved by science and by cooking. Later, as a protg of the chef Charlie Trotter, and afterwards, in his own restaurant, he became a pioneering chef who was leading us to a new future in food.

Homaro Cantu didnt just want to make you dinner. He wanted to change the world.

At the time of his death, in April 2015, he was at work on a revision of this book. He imagined it as a fitting celebration of Motos first ten years, showcasing the ten most original dishes from each year. The photography was complete, the recipes had been written, and the combination was full of Omars generous and creative spirit.

With help from his collaborators, the publisher has completed revisions on Omars behalf to prepare this book for publication. No recipes have been added or substantively changed, but methods have been further explained and measurements have been standardized. Omars comments have been edited, and a glossary has been added to aid home cooks.

It is our hope that each of these one hundred recipes opens a window into Homaro Cantus extraordinary culinary mind.

My beginnings in the restaurant business were inauspicious.

When I was very young, my mother, older sister, and I were homeless. My mother had drug addiction problems, and my father just wasnt there. I went to violent schools, and we floated from shelter to shelter, sometimes driving into the woods of the Pacific Northwest and living out of our car.

Then, when I was 11, my sister and I moved to live with our father in California. He had worked to track us down, but by the time he found us, he had started another family and had basically moved on. We didnt feel wanted. We lived on the rough side of town, and I kept getting into trouble.

I hid in a closet during recess and stole baseball cards to sell to other kids for cash. I bought pencils and sold them, tooand then made sure my customers pencils came up missing. I threw cherry bombs in the boys bathroom and damn near burned down an apartment complex. Growing up around meth and crack addicts and verbal and physical abusers took its toll on me. I was an out-of-control fuckup, headed for jail or addiction.

One of the most meaningful moments in my life came in the seventh grade, when my science teacher took an interest in me. Mr. Moore saw that I was floundering and threw me a challenge. You are a real joker, but I bet you have a couple of useful marbles upstairs, Omar. If you read an article from Popular Science and give me a full report, Ill give you an A.

Do one report so I can screw around the rest of year? Sign me up. The article was about an emerging technology called superconductors. Mr. Moore said, Something tells me youd have a knack for this stuff. When you joke around in my class and disrupt others, I think you are actually bored with what we do here. Am I right?

I had never thought of that, but I did like taking things apart to understand how they worked. In fact, I spent that summer taking apart my dads lawnmower and putting it back together.

The next day I made my full report, and Mr. Moore encouraged me to enter a science competition, building a rocket out of a two-liter bottle. I won first place. For the first time in my life, I was good at something. Mr. Moore didnt give me the answers but rather encouraged me to be artistic and use science to compete. It was a turning point for me.

Around that time I got my first real job. I lied about my age and started working at a fried-chicken joint. The food was awful, but I was fascinated by the restaurant and loved working with the cooks. I finally felt at home.

After graduating from culinary school, I worked everywhere from Spago in Beverly Hills to a Burger King in Orange County. I wanted to end up at a fine-dining restaurant but was willing to work anywhere that would teach me something new. I filed it all away for my own future use.

In 1999, I flew to Chicago with a backpack, $350, and just enough guts to ask for a tryout at Charlie Trotters restaurant. I stayed for four years and left with the title of sous chef and a million unforgettable experiences.

Charlie was a god. I paid careful attention to every move he made. I copied his vocabulary and tried to think like he did. And I worked hard. Whatever they piled on, I did it, no matter how insane it looked or sounded. When someone mentioned a chef I had never heard of, I looked him up and read all night. I tried to move a little quicker every day. I was always thinking of ways to increase efficiency, improve flavor, and make the best possible product I could.

For a long time, I was only happy at Trotters. I got four hours of sleep a night and could barely pay my rent. But motivation has to come from within, and I had found mine. Technology and science helped me to become a chef. Focusing on the present made the past nonexistent. I had all this creativity I was dying to unleash.

Eventually, I got an executive chef position at a restaurant that was still under construction. Before it opened, I convinced the investors to change their original concept to a tasting menu restaurant that incorporated the inventions I had been tinkering with. I began to work full-time on bringing those crazy ideas to life. That restaurant became Moto.