Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

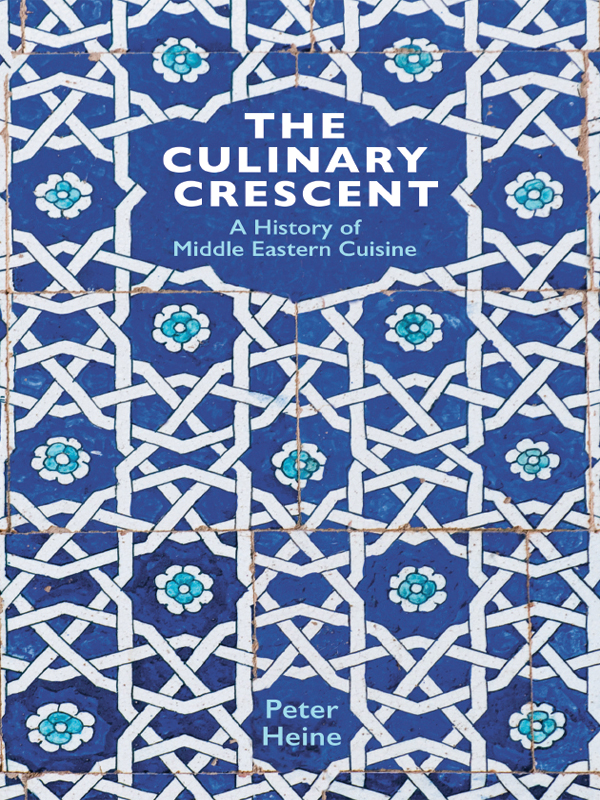

Falafel, hummus and doner kebabs; couscous, stuffed vine leaves and marzipan the delicacies of the Middle East have long since found their way onto menus in the West, while spices such as cloves, cardamom, saffron and cinnamon that were once beyond most peoples means are today familiar ingredients in every well-appointed kitchen. But how much do we really know about Middle Eastern cuisine?

In this book, the renowned Islamic scholar Peter Heine explains, among other things, why Muslims never eat pork, but are not infrequently partial to a glass of red wine. He goes on to describe the kinds of dishes that were prepared in the Thousand and One Saucepans of the Ummayads, Abbasids, Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals and how almsgiving came to be considered part of good etiquette at table. The author recounts tales of the great Middle Eastern chefs and cooks, both male and female, of the distribution of different vegetables and fruit across the region and the routes by which they were brought to Europe, and of how the supply of halal produce worldwide has now become a multi-million pound industry.

Since Heine is also an avid gourmet, this unique cultural history is garnished with over a hundred recipes, including everyday dishes for the modern kitchen, classic preparations from the annals of Mughal and Abbasid cookery, and lavish confections that conjure up the culinary delights of Paradise.

Peter Heine

THE CULINARY

CRESCENT

CRESCENT

A History of

Middle Eastern Cuisine

Translated by Peter Lewis

First published in English in 2018 by Gingko Library

4 Molasses Row

London SW11 3UX

First published in German as Kstlicher Orient by Peter

Heine, 2016 Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin

English language translation copyright Peter Lewis 2018

Cover illustration: Julie August from a photo of an Uzbek

mosaic Konstantin Kalishko / depositphotos

The rights of the author has been asserted in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotation in a review,

no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by

any electronic or mechanical means, including information

storage and retrieval systems, without written permission

from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for the book is available from the

British Library.

ISBN 9781909942257

eISBN9781909942264

Layout by Denise Sterr

Typeset by Mitchell Onuorah in Minion Pro and Gill Sans

Printed in Spain

www.gingko.org.uk

@gingkolibrary

Prologue

The German scholar Adam Mez, who founded the School of Islamic Studies at Basel University in Switzerland, is thought to have been the first person to produce an intensive study of the role played by eating and drinking in Islamic societies. All he had at his disposal were literary and historical sources. Accordingly, the end result was a somewhat skewed picture of medieval Oriental cuisine by which he meant principally Arab cuisine. The first medieval Arab cookbook to come to light, which was only edited as late as 1934 by the Iraqi scholar Daoud Chelebi, was translated into English five years later by the British Arabist Arthur John Arberry. In 1949, research into the culinary history of the Islamic world took a great leap forward with the completion of a doctoral dissertation by the French orientalist Maxime Rodinson (19152004) entitled Recherches sur les documents arabes rlatifs la cuisine (A study of Arab documents on the subject of cookery and food). This was the first account of Arab/Islamic cuisine to proceed from the basis of a cookbook. In addition, Rodinson, who was influenced by the contemporary Annales School of French historiography, focused primarily on the social and political significance of the art of cooking in his research and addressed the question of the influence of Arab cooking on European cuisine. There followed studies of Arab cookbooks from al-Andalus (Moorish Spain) and a variety of Islamic cuisines ranging from Morocco to Indonesia, all of which have substantially enhanced our knowledge of food and drink in Muslim societies.

The great boom which has taken place in the publication of cookbooks over the last two decades or so has not passed by Eastern cuisines. Thanks to her encyclopaedic knowledge of the culinary traditions and cuisines of the Near and Middle East, the most important author in this regard has been Claudia Roden (b. 1936), who since the late 1960s has produced numerous volumes containing recipes she has collected and notes on the cultural history of food, along with anecdotes and autobiographical observations.

The majority of cookbooks on individual countries of the Islamic world are devoted to the cuisine of Morocco; the doyenne of this particular field is the French author Zette Guinaudeau-Franc. One of the first writers to introduce an English-speaking audience to the real cuisine of the Middle East was Elizabeth David (19131992). Her celebrated first work, A Book of Mediterranean Food (1950), included recipes and ingredients that harked back to the time she had spent in Cairo and Alexandria in British-occupied Egypt during the Second World War.

Further references to cookbooks and works on the cultural history of food and drink in the Islamic world can be found in the Bibliography section.

No Pork, no Alcohol

O you who believe! Eat of the good things which We have provided for you and be grateful to Allah if it is Him that you worship. Thus declares Surah 2, verse 172 of the Quran, the holy book of Islam. Whereas other religions tend to treat eating and drinking as mere necessities for the maintenance of life, Islam also regards these functions as manifestations of the perfection of the divine creation. The Quran exhorts people to delight in eating and drinking. The Prophet Muhammad, who in the view of Muslim believers had the deepest, most complete knowledge of the Quran, called the uncreated word of Allah a banquet ( maduba ) to which everyone was invited. For everyone who read it, the Prophet further elucidated, it offered the greatest diversity of dishes piquant, sweet or sour. On the other hand, the Quran admonished the faithful not to indulge in gluttony; Eat and drink, but not to excess. For He [Allah] does not love the intemperate (Surah 7:31).

Of course, in common with all other religions, Islam is not without its precepts and proscriptions. However, in comparison to the dietary requirements in Judaism, these are positively simple. In Islam, there are rules relating to eating and fasting. Prior to eating, a person must wash their hands and invoke the name of God before partaking of their first mouthful. It is equally important to eat only with ones right hand. As far as fasting is concerned, there are certain days and periods during which people are enjoined to refrain entirely from taking food and drink, others on which fasting is allowed, and finally yet others on which fasting is forbidden. Hence, fasting is prohibited on the feast days of Eid al-Adha (The Feast of the Sacrifice) and on Eid al-Fitr , the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, the Islamic holy month of fasting, as well as on every Friday except those which fall in Ramadan. Dietary taboos, on the other hand, relate almost exclusively to the consumption of pork and alcoholic beverages. To the devout Muslim, pork in any form is harm that is, strictly forbidden.

CRESCENT

CRESCENT