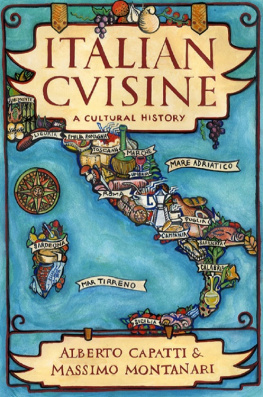

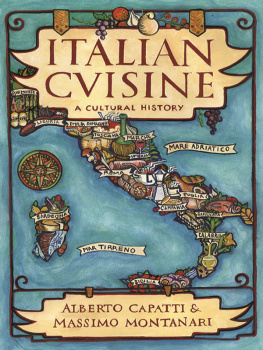

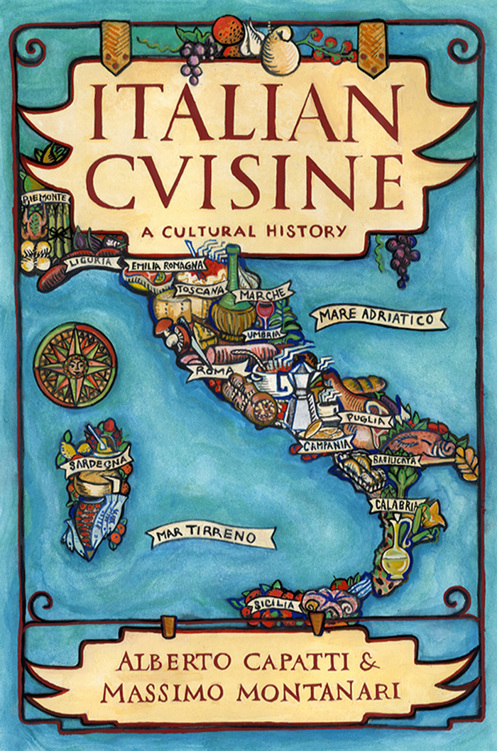

alberto capatti & massimo montanari translated by aine ohealy

columbia university press new york

columbia university press new york

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

Copyright 1999 Gius. Laterza and Figli SpA

Translation copyright 2003 Columbia University Pres s All rights reserve d

This translation of La cucina Italiana: Storia di una cultur a is published by arrangement with Gius. Laterz a and Figli SpA, Rome-Bari .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Dat a Capatti, Alberto, 1944 [Cucina italiana. English ] Italian cuisine : a cultural history / Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari . p. cm. (Arts and traditions of the table ) Includes bibliographical references and index . isbn 12232 (alk. paper ) . Cookery, ItalianHistory. . ItalySocial life and customs . . GastronomyHistory . I. Montanari, Massimo, 1949 II. Title. III. Series .

TX .C 28313 2003 641 . 5945 ' dc 21 2003044009

Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper.

Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Linda Secondari

c 10987654321

To Libista, a peasant woman fro m Cernuschio in Lombardy , who invented ravioli wrapped in doug h

contents

Series Editors Preface xi i Introduction: Identity as Exchange xii i

chapter one

Italy: A Physical and Mental Space Mare Nostrum From the Mediterranean to Europe From Europe to Italy The Fifteenth-Century Definition of the Italian Model Lists of Things... Generally Used in Italy Itineraries Toward Regionalization Municipal Recipe Collections Artusi and National-Regional Cuisine The Mediterranean Again

chapter two

The Italian Way of Eating

Flavors and Fragrances from the Vegetable Garden Polenta, Soup, and Dumplings The Invention of Pasta Torte and Tortelli The Pleasure of Meat Eating Lean Food: The Liturgical Calendar and the Cooking of Fish Milk Products Eggs Cooked Food and Preserved Food A New Sense of Typicality

chapter three

The Formation of Taste

Flavor and Taste The Culture of Artifice The Legacy of Rome The Arabs: Innovation and Continuity Spices Sweet, Sour, and Sweet-and-Sour The Triumph of Sugar The Humanists, Antiquity, and Modernity The Flavor of Salt Oil, Lard, and Butter The Italian Model and the French Revolution Waters, Cordials, Sorbets, and Ice Creams Can One Cook Without Spices? Toward the Development of a National Taste

chapter four

The Sequence of Dishes

The Galenic Cook The Things That Should Be Eaten First The Meager Repast Organizing and Presenting the Banquet The Choice of Wine The Bourgeoisie Cuts Back The Death of the Appetizer and the Resurrection of Cheese The Single Dish

chapter five

Communicating Food: The Recipe Collection

The Book Title, Frontispiece, and Portrait Dedications and Tributes The Organization of Contents and Indexes The Recipe The Menu

chapter six

The Vocabulary of Food

A Chronological Outline Latin

The Vernacular Franco-Italian Order and Cleanliness Linguistic Autarchy Italian in the Kitchens of Babel

chapter seven

The Cook, the Innkeeper, and the Woman of the House

Recorded Lives The Kitchen Brigade Costume and Custom The New Innkeeper From Housewife to Female Cook

chapter eight

Science and Technology in the Kitchen

Tradition and Progress The Popes Saucepans A Virtual Discovery: The Pressure Cooker Artificial Refrigeration Appert in Italy: The Flavor of Preserved Foods The Oven, the Sorbet Maker, and Simple Machines Metal Alloys and Ice Cubes The Magic Formula

chapter nine

Toward a History of the Appetite

The Hearty Eater To Stimulate the Appetite Indigestion Does No Harm to Peasants The Diet of the Literary Man The Bourgeois Belly Down with Pasta! The Repression of the Body and the Virtual Dish

Notes Bibliography Index

series editors preface

What is the glory of Dante compared to spaghetti? is among the memorable lines in this prodigiously learned yet always readable and entertaining book. The authors have in fact written a veritable diachronic encyclopedia, and how refreshing it is for once to read a chronologically grounded exposition. A chap ter devoted to science and technology in the kitchen traces cooking tech niques, utensils, and devices as they progressed from Roman antiquity through the Middle Ages to the present. In so doing, Capatti and Montanari connect var ious forms of government, regional topographies, and economies (since Italys well-documented regionalism leads at times to a specifically local culinary vocabulary and technology).

But what emerges from this book is that, regionalisms aside, there is a national Italian culinary culture. In a compelling study of the linguistic resources of cook books and menus, the authors demonstrate how the amazing number of Italian cookbooks published from the Middle Ages onward evolved from Latin, at the outset, through the courtly seventeenth-century French (and its on-going snob appeal), into a Tuscan-Italian still burdened by a thick web of gastronomic Gal licisms. In this richly documented chapter (really a history unto itself) recipes from the thirteenth through the sixteenth centuries are adduced to trace the Orphic naming of new products unknown to the early Romans. All this, with a full authorial awareness of political and social developments, makes for a fasci nating narrative.

Equally intriguing is the history of military diets: how availability of products in specific locales of conflict and the need to feed troops on the battlefield led to new technologies and tested the limits of culinary availability. At the same time, the military regime, especially during World War I, forged a national diet that led to the unity of what we now know as la cucina italiana .

Linked to the military is the evolution of chefs, cooks, and servers attire in restaurants. The absurdity of highly formal tails for headwaiters, say, maintained in our own era of vestimentary informality, reflects the same military hierarchi cal order found in the emblem of the toque itself. Only the officers (matres d, executive chefs, et al.) were allowed beards and mustaches; as immediate inferiors, underlings and servers had to be clean-shaven in deference.

columbia university press new york

columbia university press new york

Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper.

Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper.