ITALIAN CUISINE

Arts and Traditions of the Table

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE: PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

Albert Sonnenfeld, series editor

Salt: Grain of Life

Pierre Laszlo, translated by Mary Beth Mader

Culture of the Fork

Giovanni Rebora, translated by Albert Sonnenfeld

French Gastronomy: The History and Geography of a Passion

Jean-Robert Pitte, translated by Jody Gladding

Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food

Silvano Serventi and Franoise Sabban, translated by Antony Shugar

Slow Food: The Case for Taste

Carlo Petrini, translated by William McCuaig

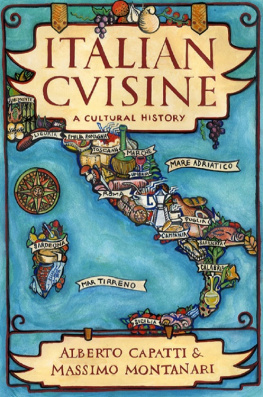

ITALIAN CUISINE

A CULTURAL HISTORY

ALBERTO CAPATTI & MASSIMO MONTANARI TRANSLATED BY AINE OHEALY

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 1999 Gius. Laterza and Figli SpA

Translation copyright 2003 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50904-6

This translation of La cucina Italiana: Storia di una cultura is published by arrangement with Gius. Laterza and Figli SpA, Rome-Bari.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capatti, Alberto, 1944[Cucina italiana. English]

Italian cuisine: a cultural history /

Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari.

p. cm. (Arts and traditions of the table)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-12232-2 (alk. paper)

1. Cookery, ItalianHistory. 2. ItalySocial life and customs.

3. GastronomyHistory.

I. Montanari, Massimo, 1949

II. Title. III. Series.

TX723.C28313 2003

641.594509dc21

2003044009

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

To Libista, a peasant woman from Cernuschio in Lombardy, who invented ravioli wrapped in dough

CONTENTS

What is the glory of Dante compared to spaghetti? is among the memorable lines in this prodigiously learned yet always readable and entertaining book. The authors have in fact written a veritable diachronic encyclopedia, and how refreshing it is for once to read a chronologically grounded exposition. A chapter devoted to science and technology in the kitchen traces cooking techniques, utensils, and devices as they progressed from Roman antiquity through the Middle Ages to the present. In so doing, Capatti and Montanari connect various forms of government, regional topographies, and economies (since Italys well-documented regionalism leads at times to a specifically local culinary vocabulary and technology).

But what emerges from this book is that, regionalisms aside, there is a national Italian culinary culture. In a compelling study of the linguistic resources of cookbooks and menus, the authors demonstrate how the amazing number of Italian cookbooks published from the Middle Ages onward evolved from Latin, at the outset, through the courtly seventeenth-century French (and its on-going snob appeal), into a Tuscan-Italian still burdened by a thick web of gastronomic Gallicisms. In this richly documented chapter (really a history unto itself) recipes from the thirteenth through the sixteenth centuries are adduced to trace the Orphic naming of new products unknown to the early Romans. All this, with a full authorial awareness of political and social developments, makes for a fascinating narrative.

Equally intriguing is the history of military diets: how availability of products in specific locales of conflict and the need to feed troops on the battlefield led to new technologies and tested the limits of culinary availability. At the same time, the military regime, especially during World War I, forged a national diet that led to the unity of what we now know as la cucina italiana.

Linked to the military is the evolution of chefs, cooks, and servers attire in restaurants. The absurdity of highly formal tails for headwaiters, say, maintained in our own era of vestimentary informality, reflects the same military hierarchical order found in the emblem of the toque itself. Only the officers (matres d, executive chefs, et al.) were allowed beards and mustaches; as immediate inferiors, underlings and servers had to be clean-shaven in deference. Another favorite chapter (chapter nine) traces the history of appetite. How much did medieval Florentine merchants consume to celebrate the prosperity of their nascent bourgeois society [which they themselves called il popolo grasso (the stout people)]? What foods constituted a satisfying diet for the glutton? How did this contrast with the regimen in monasteries? And how did the liturgical calendar, with its distinction between fat and lean days and its repertoire of symbolic foods, affect production, economics, and development of those specifically Italian culinary traditions so easily contaminated by their ancient Roman ancestry?

To be sure, there are other histories of Italian cuisine, but none are as richly documented as the present volume, which nevertheless remains eminently accessible and pleasurable. This monumental grouping of a constellation of culinary histories convinces us incontrovertibly of both the diversity and the unity of la cucina italiana.

Albert Sonenfeld

Italy, the country with a hundred cities and thousands of bell towers, is also the country with a hundred cuisines and thousands of recipes. Mirroring a history marked by provincial loyalties and political division, a huge variety of gastronomic traditions makes Italys culinary heritage unimaginably rich and more appealing today than the cuisine of any other country, now that the demand for diversity and for distinctive, provincial flavors has become especially keen. Variety is also the element that immediately strikes the visitors eye and palate. Is this enough to conclude that an Italian cuisine in the strict sense has never existed and (fortunately, perhaps) does not exist even today?

This is what one is often led to believe, but the task of this book is to show the contrary, based on a series of considerations that do not strike us as self-evident. Rather, they tend to undermine certain commonplaces, as well as the more usual ways of approaching culinary history. Because this book is entirely organized around a few fundamental themes, we would like to clarify them at the outset.

In the first place, we must restore to culinary history its own particular dimension. The temptation to subordinate this history to the hegemony of literatureregarded for centuries as the highest and most authoritative expression of good tastehas led to contradictory results. On the one hand, there is the attempt to show that patterns of consumption and styles of conviviality reflect an ideal of civility; on the other, there is the ongoing tendency to consider the minor, material arts as subordinate to the major, intellectual ones. To see a baroque stamp on seventeenth-century cuisine, like the rational character attributed to the cuisine of the Enlightenment, has been a means of ennobling diet and food, of talking about culinary matters by alluding to something else. But cooking does not require analogies. It has its own history and documentary autonomy, even if it can (and should) be studied by consulting many different sources, including literature.

Next page

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK