Contents

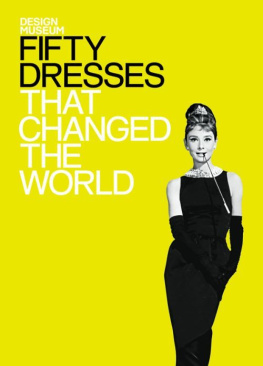

Meryl Streeps character in The Devil Wears Prada (2006) makes a powerful pitch for understanding the significance of fashion, especially to those who see in it nothing but the frivolous and the self-indulgent. The colour of the sweater, she says, made in the Far East, on an industrial scale, providing work for poor families, and putting a developing economy on the road to the First World, is the afterglow of a couture collection.

Fashion can be understood in many ways. It is both an industrial and a cultural phenomenon, one that goes to the heart of what we understand as design. The Industrial Revolution in Britain was fuelled by technical innovation in manufacturing textiles. Contemporary fashion is a huge and extremely vigorous industry, of which the catwalk collections provide only a glimpse. That is why fashion continues to be an important part of the Design Museums programme.

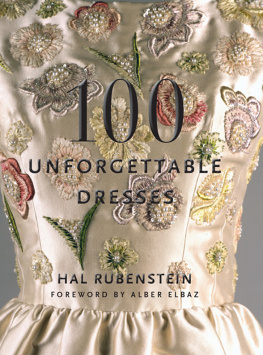

The collection of iconic dresses included in this book provides an introduction to the path fashion has taken in the past century. It is a story that embraces social and economic change and radically fluctuating positions on gender and sexuality. These are dresses that have encapsulated particular moments in time in a particularly powerful way, and that have provided fascinating insights into the people who wore them as well as the people who designed and made them.

Deyan Sudjic, Director, Design Museum

Technology and wearable style combine in the hauntingly illuminated LED dress from Hussein Chalayans 2007 Airborne collection.

Mariano Fortuny

As the twentieth century began, the accumulation of scientific knowledge, technical developments and cultural questioning that had preoccupied the previous decades brought about accelerated societal change. There was never a more fitting time for fashion to adopt a responsive visual language that would keep up with, and sometimes guide, the rapid pace of modern life. In this headlong rush towards modernity, however, the appropriation of novel technologies and materials often went hand in hand with a reinterpretation of traditional styles and techniques.

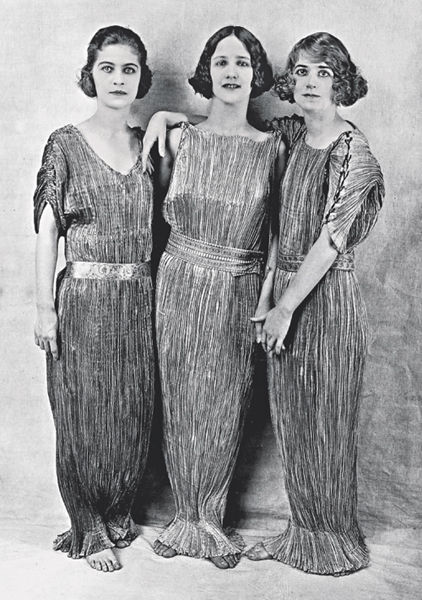

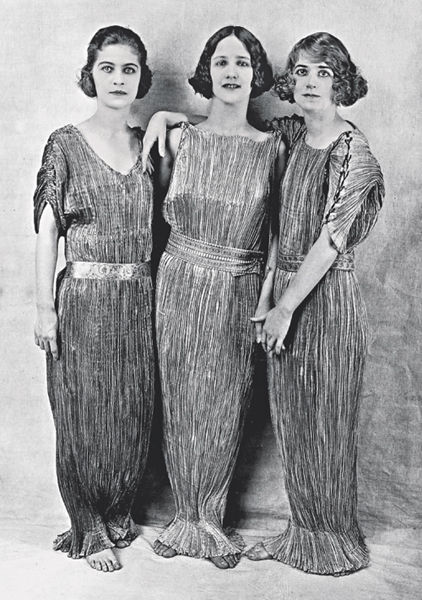

In 1909 the Spanish-born couturier Mariano Fortuny (18711949) patented a method of pleating silk that enabled him to produce flowing, romantic gowns that were quickly taken up by the European artistic elite. A far cry from the constricting costumes of the nineteenth century, these loose, lightweight dresses allowed a radical freedom of movement, even as they daringly emphasized the contours of the female form. Despite their liberating modernity, however, Fortunys designs were rooted in tradition and often referenced antique and other historical styles.

Perhaps Fortunys greatest achievement, the Delphos dress is a reinterpretation of the draped and flowing clothing of ancient Greece. Through the structural quality of the pleating, it captures all the sensuality and romance of the era, as imagined by late nineteeth-century academic painters such as Sir Frederick Leighton. This pleating technique was a closely guarded secret and has never been successfully copied since.

The Delphos dress accentuated the natural shape of the figure and allowed a revolutionary freedom of movement.

Three variations of Fortunys groundbreaking pleated dress.

Coco Chanel

Boyishly bobbed hair and the short-cut shift dress became the uniform of emancipated modern young women in the mid-1920s. With their slang, exposed limbs and go-getting attitude, these flappers showed defiance, daring and strength in a male-dominated world. The flapper dress was a physical liberation, overthrowing the tyranny of the corset and, more prosaically, cutting down the time it took to get dressed. But the garment also reflected social change, as a new generation of middle-class women challenged the gender and class repressions of the past.

The look associated with flappers was pioneered in the neutral-toned and simply cut designs of Coco Chanel (18831971). Made from utilitarian jersey fabrics, her clothes were about comfort and ease of movement with a loose silhouette that abandoned a tucked-in waist and mounds of heavy fabric. The simplicity of these dresses also meant they could be easily run up at home, making the look accessible to the masses it was one of the first trends not to be restricted to the wealthy or a fashion elite.

However, this was a short-lived style, thwarted at the end of the decade by the economic collapse of 1929. Times now became too serious for lighthearted defiance, and it would be nearly 40 years before hemlines would rise again.

The constrictions of corsets and padding were swept away as the loose-fitting utilitarian flapper dress gave everyday liberation to modern working women.

Madeleine Vionnet

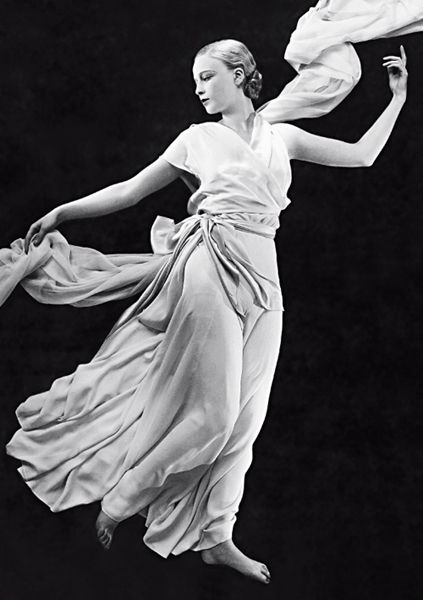

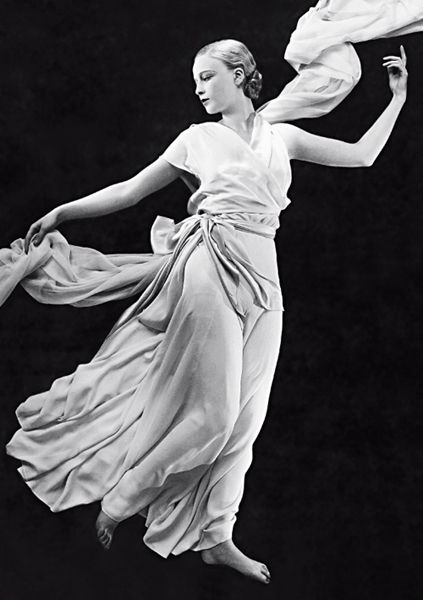

The catastrophe of World War I brought about a radical reappraisal of gender, class and creativity. There was a freedom in the air that enabled a few to break away from convention and explore new horizons. Just as the dancer Isadora Duncan combined a passion for the Classical world with a natural and sensual approach to the human body, the French designer Madeleine Vionnet (18761975) looked back to ancient Greece as she sought to liberate women from the constraints of corsets and padding.

Vionnets bias-cut dresses allowed fabric to float freely around the body, enhancing natural curves and accentuating though not moulding the female form. Women were free to express a softer femininity. The style depended on an expert understanding of pattern cutting and the properties of fabric. Vionnet is often credited with establishing the bias cut as one of the staples of modern fashion certainly, she understood perfectly that to cut cloth on the diagonal made it more flexible and elastic and therefore much easier to drape.

Simple and spontaneous as the Vionnet style appears, it entailed meticulous attention to detail. Designs were carefully worked out on miniature dolls before being made up as full-sized finished garments.

With bohemian licence in the air Madeleine Vionnets bias-cut designs created freedom of movement for the new breed of 1930s women.

Mainbocher

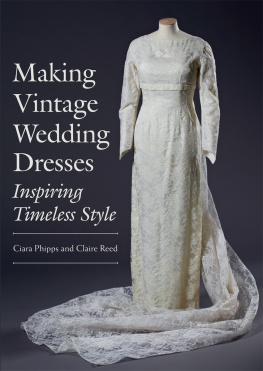

American socialite Wallis Simpson was married in 1937 dressed in a simple floor-length gown with matching long-sleeved jacket all in Wallis Blue, a colour specially developed to match her eyes. Created by the United States-born but Paris-based designer Mainbocher (Main Rousseau Bocher 18911976), this understated gown would become one of the most copied dresses of all time.

The wedding was the culmination of the scandal of the century. The Duke of Windsors uncompromising love for the divorcee had forced him to abdicate from the British throne the previous year, provoking a constitutional crisis that had shaken the British establishment to the core. However, to a US audience less concerned with royal protocol and tradition, it appeared only that a strong American woman had succeeded in obtaining true love in the face of adversity and criticism.

Next page